Artist Led, Creatively Driven

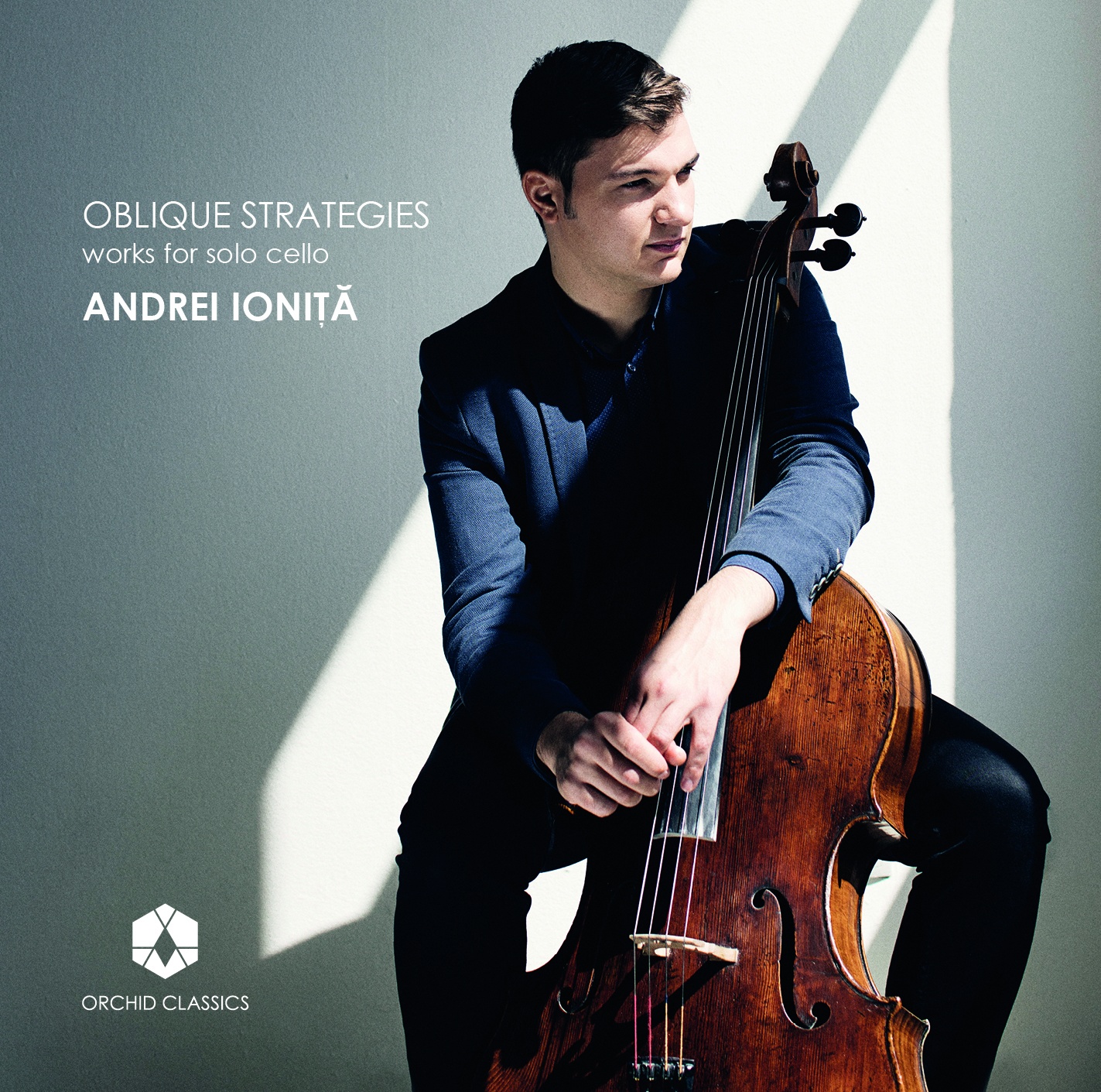

Oblique Strategies

Andrei Ionita, cello

Release Date: 15th March 2019

ORC100096

OBLIQUE STRATEGIES

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Cello Suite No.1 in G major, BWV1007

1 Prelude 2.26

2 Allemande 4.07

3 Courante 2.26

4 Sarabande 3.07

5 Minuet 1 & 2 3.02

6 Gigue 1.51

Brett Dean (b.1961)

Eleven Oblique Strategies (world premiere recording)

7 Listen to the quiet voice 2.18

8 A line has two sides 0.41

9 Don’t stress one thing more than any other 0.38

10 Look at a small object, look at its centre 0.45

11 What are the sections sections of? 1.59

12 Don’t be frightened to show your talents 1.52

13 Disciplined self-indulgence 0.45

14 Bridges –build – burn 1.03

15 Ghost echoes 2.32

16 Disconnect from desire 2.00

17 In a very large room, very quietly 1.32

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967)

Sonata for solo cello in B minor, Op.8

18 Allegro maestoso ma appassionato 9.32

19 Adagio (con grand’espressione) 12.50

20 Allegro molto vivace 12.06

Svante Henryson (b.1963)

21 Black Run (from North American Suite) 3.22

Total time 70.58

Andrei Ioniţă, cello

Dating Bach’s instrumental works precisely is in many instances impossible – especially in the cases of those pieces that remained unpublished during his lifetime and in some instances for many years afterwards. Some works have come down to us in manuscripts not in the composer’s own hand: the most important source for the six suites for unaccompanied cello, for example, is a copy made by the composer’s second wife, Anna Magdalena Bach.

There is general agreement, though, that the cello suites date from the period 1717 to 1723, when the composer was employed as Kapellmeister to the music-loving Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen, and probably composed for a member of the court orchestra.

In terms of structure they conform to Bach’s standard pattern for the genre: in each instance there’s an opening prelude, followed by a sequence of movements in dance form in the regular order Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue. In between the final two comes an additional pair of movements, collectively referred to as Galanterie (meaning a courtesy): here Bach includes two minuets, though in other instances he might use such alternative forms as the Loure or the Gavotte.

The first suite opens with a Prelude flowing in constant semiquaver motion that has arguably become the best known movement in the entire set of suites and an almost iconic example of Bach’s writing for solo cello. This is followed by an Allemande that traverses the instrument’s entire range and a vital Courante notable for its melodic leaps. Next comes a stately Sarabande that makes a feature of double- and triple-stopping – the art of sounding two or even three strings simultaneously (or very nearly so), followed by the two Minuets – the first jocular, the second more serious and in the minor key. The final movement is a sturdy Gigue.

Throughout the suite Bach’s ability to create a convincingly rich harmonic structure while essentially employing just a single line to do so is a demonstration of his outstanding compositional skill – something equally evident in the works of the Australian composer and instrumentalist Brett Dean.

He was born in Brisbane in 1961 and at the age of 8 began to learn the violin, later moving onto the viola and becoming a leading exponent of the instrument: between 1985 and 1989, for instance, he was a member of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Herbert von Karajan.

Since 2000 he has been a freelance musician and a composer of increasing prominence and reputation: such works as his operas Bliss (2010) and Hamlet (2017) and his The Lost Art of Letter Writing for violin and orchestra (2007) have all been extremely well received. On this recording we hear a piece written for the Grand Prix Emanuel Feuermann, held in Berlin in November 2014 – an occasion when Andrei Ioniţă was himself a prize-winner.

As Dean himself explains, ‘The term “oblique strategies” was coined jointly by British musician Brian Eno and German-born British visual artist Peter Schmidt to describe a series of printed cards they developed throughout the 1970s. The cards had their origins in sets of uncannily similar working principles that both artists had established independently, and featured aphorisms intended as a means of triggering inspiration or providing useful stimulus during the creative process.’

Dean chose of eleven of these, ‘ordering them in a way that revealed to me a logic and potential inter-relatedness within a hitherto disparate set of single ideas I had assembled for solo cello.’ The result is a striking collection of expertly written character pieces, full of varied technical and interpretative challenges.

One of the greatest works for solo cello is undoubtedly the Sonata by Zoltán Kodály. The Hungarian composer wrote it in 1915 for Jenö Kerpely – the cellist in the Waldbauer-Kerpely Quartet which had already championed his own music as well as that of his friend and colleague Bartók; Kerpely premiered the piece in Budapest in 1918.

The result is a giant contribution to the instrument’s repertoire, a work that in its musical and expressive range explores the instrument and its potential to an unprecedented degree.

An unusual feature is its use of scordatura, or retuning: the instrument’s two lowest strings are further lowered to B and F sharp respectively, as opposed to the standard C and G: this reflects the key of the piece – B minor – which makes crucial use of these two notes as tonic and dominant respectively.

Throughout his life Kodály made a profound study of folk music, especially from his native land: and although he does not quote any examples in the present work it permeates the sonata’s musical language at a fundamental level. It is a feature immediately evident, for instance, in the grand-scale opening movement, whose alternately fierce and soulful but invariably highly charged lyricism charts a rhapsodic course that nevertheless outlines the essential elements of sonata form in its overall structure.

Following a ruminative introduction that recurs later on in expanded form, the main theme of the ternary-form slow movement is a freely moving, decorated melody with the character of a folk lament. This idea leads us on a powerfully emotional journey, initially pinned to a stark, monotonous bass. The frenetic middle section is succeeded by a return to the opening melody, now in amplified and more ornately decorated form.

The finale turns to insistently punchy rhythms, its energetic ideas forged from strenuous folk-dance impulses occasionally and briefly held back only to return with even greater dynamism. Once again the exploratory nature and extravagant inventiveness of the writing take both the performer and the instrument itself to their respective limits.

Born in Stockholm in 1963, Svante Henryson enjoys a varied career that takes in more than one instrument and a huge diversity of contemporary music. He began as a bass guitarist in a rock band at the age of 12, moving on to jazz and the double bass and later classical music: by 1983-4 he was principal double bass in the World Youth Orchestra, subsequently holding the same position in the Oslo Philharmonic and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra. He has continued to collaborate with leading musicians in jazz, pop, classical and other fields while simultaneously building up a substantial catalogue of his own orchestral, choral and chamber works.

Black Run (2001) – which can be performed with optional percussion accompaniment – is a brilliant piece of virtuoso writing exploring a myriad of techniques and textures along its short but entertaining bluegrass-inspired path.

© George Hall

ANDREI IONIŢĂ

“One of the most exciting cellists to have emerged for a decade”

Anna Picard, The Times

Andrei Ioniţă won First Prize at the 2015 International Tchaikovsky Competition, and prizes at the ARD, Emanuel Feuermann and Aram Khachaturian competitions. He was a BBC New Generation Artist between 2016-18.

Andrei has already performed with the Münchner Philharmoniker, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Mariinsky Orchestra, Saint Petersburg Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, BBC Philharmonic, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, The Hallé, Tokyo Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony and Rochester Philharmonic; working with conductors such as Valery Gergiev, Cristian Macelaru, Mikhail Pletnev, Karl-Heinz Steffens, John Storgårds and Omer Meir Wellber.

He has given recitals at Carnegie Hall, Wigmore Hall, Zurich Tonhalle, Konzerthaus Berlin, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, L’Auditori Barcelona; and at the Kissinger Sommer, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schleswig-Holstein, Verbier and Cheltenham Festivals.

Born in 1994 in Bucharest, Andrei began taking piano lessons at the age of five and received his first cello lesson three years later. He studied under Ani-Marie Paladi at the Iosif Sava Music School in Bucharest and Professor Jens Peter Maintz at the Universität der Künste in Berlin, where he currently resides.

Andrei is a scholarship recipient of the Deutsche Stiftung Musikleben and performs on a Giovanni Battista Rogeri violoncello made in Brescia in 1671 on loan from the foundation.

Sunday Times

‘The recent BBC New Generation Artist’s debut makes for impressive listening…’