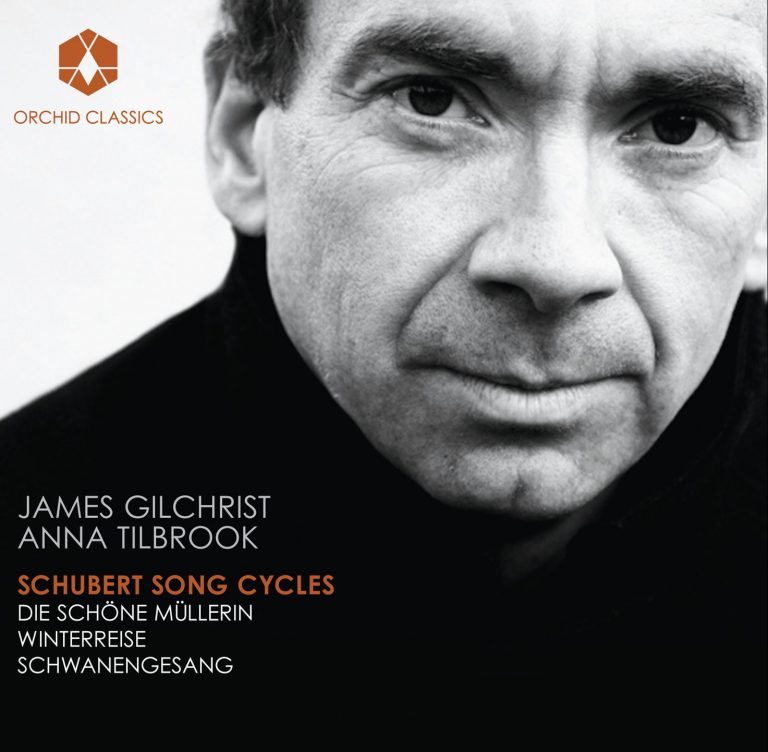

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

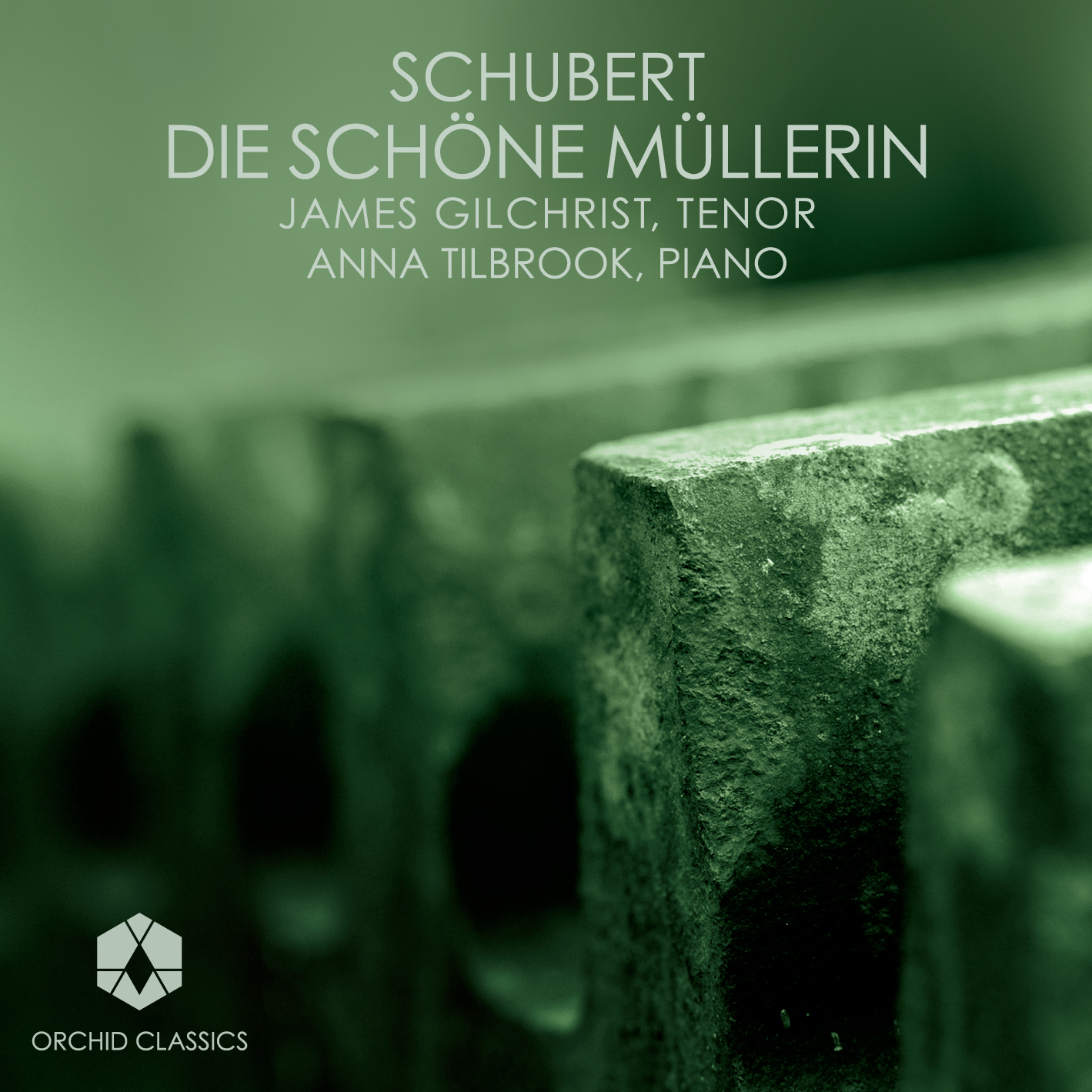

Schubert

Die Schöne Müllerin

James Gilchrist

Anna Tilbrook

Release Date: October 2009

ORC100006

FRANZ SCHUBERT

Die Schöne Müllerin

Das Wandern

Wohin?

Halt!

Danksagung an den Bach

Am Feierabend

Der Neugierige

Ungeduld

Morgengruß

Des Müllers Blumen

Tränenregen

Mein!

Pause

Mit dem grünen Lautenbande

Der Jäger

Eifersucht und Stolz

Die liebe Farbe

Die böse Farbe

Trockne Blumen

Der Müller und der Bach

Des Baches Wiegenlied

James Gilchrist, tenor

Anna Tilbrook piano

DIE SCHÖNE MÜLLERIN

by James Gilchrist

In Die Schöne Müllerin – the beautiful maid of the mill – we are told a story. It’s a straightforward tale of a young man looking for love and being disappointed, but Schubert and Müller have here created a work of huge power and depth, where we explore this tragedy with great empathy and pity, but also with our hearts full of despair at our own inability to alter the relentless logic of fate.

A young man has been apprenticed at a mill, and begs leave of his master to go out into the world and seek his own living. He follows a stream running down the hillside, reasoning that mill-wheels are turned by streams, so he’s sure to find a mill ere long. And by the third song, we have already arrived. The lad is taken on, and to his astonishment and delight finds that here he has found not only work for his hands, but enough for his heart too. For the miller’s daughter – the maid of the title – has quite bewitched him. He is instantly, utterly in love. The green spring world rejoices with him. He gives her the green ribbon from his lute. But of course he fails to notice that her feelings for him are not equal to his. An unwelcome visitor arrives – a huntsman, virile and attractive – whom the maid seems to find delightful. The colour green mocks him: the colour of innocence and spring and hope has turned to the colour of the hunt and of envy. The world is full of green and everywhere it now tortures him. Thrown into despair, he seeks council from the only true friend he has ever had: the stream running by the mill. And seeing this as the only means to peace, he flings himself under the waves.

For a tale of such sadness, it is striking that so much of the work is deliciously happy. It is bursting with tunes which even at a first hearing, one feels one has known for ever. The brook is effortlessly portrayed with rippling motifs, and its bubbling carries us merrily onward. We are given happiness, hope, youthful vigour, trust, and a deep delight in the natural world. And love: for he is quite overwhelmed by love. We sit with him enraptured. Time stands still. Every movement of leaf, cloud or star takes on a deep and special significance and meaning. For me this stasis in the middle of the work is crucially important: in “Tränenregen” we have one of the few moments that the two young people spend any time together. But there is no kiss, no touch, no word. He is unable even to look at her directly, but gazes at her reflection in the water. The power of his emotions overwhelms him, and he begins to weep. The banal words she – embarrassed – utters take on huge significance for him, and confirm him in his delusion of love. And so when his world tumbles, it falls from a great height, and falls rapidly. The last few songs of rage, despair and misery come headlong at us. The final song is a lullaby sung by the brook as it gently rocks its dead son and washes away his cares and troubles.

Die Schöne Müllerin is widely recognised as a masterpiece of the song genre. It is well known and much loved. Anna and I have been enormously lucky to perform this glorious work many times over many years on modern pianos and instruments more like those with which Schubert would have been familiar. As with all great works of literature and art, it is sometimes surprising to discover that what has moved countless people for many generations moves us deeply today as well, as freshly and directly as ever.

SCHUBERT AND DIE SCHÖNE MÜLLERIN

by Richard Morrison

No background reading, no complex musical or literary analysis, no knowledge of historical context or biographical detail is really necessary to appreciate Die Schöne Müllerin . As James Gilchrist points out above, these 20 songs speak passionately and poignantly for themselves. Together they comprise one of the great musical journeys: a journey from light to dark; from naivety to bitterly-wrought experience; from hope to despair; from a state of youthful vitality, when all good things seem possible, to a condition that seems to preclude every option except death.

This journey is something that happens to people of all ages in all countries. That is why Die Schöne Müllerin , when performed well, continues to speak directly to performers and listeners, nearly 200 years after it was written. For some people, this direct, almost visceral link to Schubert’s inspiration is sufficient – and that’s a perfectly valid attitude. It’s not a musical or intellectual crime to be indifferent to the circumstances that brought about this miracle of sustained lyrical expression and psychological perception.

Yet those circumstances were so extraordinary, and so pertinent to the subject-matter of Die Schöne Müllerin , that knowledge of them can hugely enrich one’s understanding of this remarkable song-cycle. Simply to answer the question of why Schubert, who had already set Goethe, Schiller and the other great luminaries of German literature, should have been drawn in the summer of 1823 to the morbid poetry of a young, little-known Prussian writer, Wilhelm Müller (and drawn again four years later, when he came to compose his second great song-cycle, Winterreise), one must delve into the most traumatic year of the composer’s life.

In the early 1820s Schubert seemed to be heading for success, fame, wealth and lasting happiness. His astonishing youthful productivity during his choirboy years in Vienna (he had penned five symphonies, 300 solo songs, four masses and seven string quartets by the time he turned 20 in 1817) was now enhanced by a growing awareness of his own marketability. He had given up the schoolteaching that he detested; and the gamble was starting to pay off. In 1822 alone he pocketed 2,000 gulden from his compositions; about four times what the average “white collar” worker might earn in a year.

This increasing professional fulfilment was matched by personal contentment – or so it must have seemed to his adoring circle of friends, mostly themselves writers, painters and musicians. It was around this time that they began the tradition of “Schubertiads”: nights (immortalised in several paintings) when conversation, alcohol and music would all flow with equal freedom, with Schubert sitting at the piano for hours, regaling the company with his latest batch of songs.

True, an early love affair – with a teenage girl who had subsequently married a baker, possibly because her father regarded Schubert’s financial prospects as too flimsy – had left the young composer bruised and perhaps a touch misogynistic. “To a free man,” he confided to his diary, “matrimony is a terrifying thought these days; he exchanges it either for melancholy or for crude sensuality.” That early rejection was one reason, perhaps, why Schubert was drawn to the protagonist spurned by the beautiful miller’s daughter in Müller’s poems. (Some modern scholars also argue that Schubert also suffered from cyclothymia, a mental illness characterised by alternating high spirits and manic depression; extreme sociability and then anguished anti-social periods.) But the physical crisis that hit the flourishing young composer at the beginning of 1823 must have eclipsed everything else in the composer’s mind.

From the later memoirs of his friends one can gather that Schubert at this time led a double-life. “Inwardly a poet, outwardly a hedonist” was how a young dramatist friend, Eduard von Bauernfeld, discreetly put it. His intake of alcohol and nicotine certainly shot up in his early twenties, perhaps because it offered an easy liberation from the lonely graft and concentration of composition. Some modern commentators have speculated that Schubert took opium as well. But what’s also clear is that Schubert came under the spell of a dazzling but indolent young dandy, Franz von Schober – and that (as another of his acquaintances later wrote) Schober “won a lasting and pernicious influence over Schubert’s honest susceptibility”.

The nature of that “pernicious influence” is still a matter of heated debate. The absence of a single surviving letter from Schubert to a woman (or vice versa), and the numerous close friendships that Schubert enjoyed with men, have led some scholars to conclude that he was essentially homosexual, or perhaps bi sexual. What’s indisputable (though covered up by hagiographic biographers until the late 20th century) is that Schubert at this time enjoyed a great many nights of wild abandon – gay or otherwise. And as so many other promiscuous young men and women did in the 19th century, he paid the ultimate price.

He was diagnosed with syphilis early in 1823. The disfiguring rash appeared soon afterwards, and Schubert’s head would have been shaved. He was sent to hospital, possibly for several weeks, and spent many more weeks confined to his home. The doctors would have prescribed a special diet. But Schubert would have known what everyone in 1820s Vienna knew: that there was no cure. Syphilis was a death sentence, the only question being how long the stay of execution would last. Most victims died within four to eight years. Schubert lasted nearly six.

One can well imagine his mental condition in 1823, as the physical distress of his illness – and its fatal ramifications – took a grip on his already depressive state. Just as Beethoven had poured out his anguish about his oncoming deafness in the letter to his brothers known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, so Schubert poured his feelings into a rare poem, Mein Gebet (My Prayer). “See, annihilated, I lie in the mire, my life’s martyr path approaching eternal oblivion,” he wrote.

Yet his musical productivity barely missed a beat. Two operas date from that year, as well as the glorious incidental music to the play Rosamunde. And in the late spring of that annus horribilis – most likely while he was still in hospital – Schubert began to set the 20 poems that would become Die Schöne Müllerin .

The composer didn’t know Wilhelm Müller, who lived in Berlin. But he was an indefatigable devourer of poetry, old and new (his 600-odd songs draw on the work of no fewer than 150 writers), and Müller’s versifed story of devastatingly unrequited love must immediately have struck Schubert as ripe for musical enrichment. The poems come from a collection called “Seventy- Seven Poems from the Posthumous Papers of a Travelling Horn-Player “- and that quirky title typifies the tone of Müller’s writing, which is wry, ironic and detached rather than cloying and morose. Schubert’s music, however, is anything but detached. As with Winterreise, it draws us directly and unflinchingly into the lonely soul and delusions of the protagonist. Indeed, the work soon became elevated as one of the great defining testaments of Austro-German Romantic angst.

But it’s a seminal work in other ways as well. If not the first German-language song-cycle (Schubert would probably have known Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte, written in the same city seven years earlier), it was the first to carry a continuous narrative through more than an hour of music for a solo voice and piano. And it’s a masterly synthesis of Schubert’s other songwriting innovations. There’s the use of piano figuration, for instance, to portray important figures in the drama (notably the hated huntsman and the consoling millstream); and the telling use of major/minor modulation to give a repeated tune a sudden tragic twist. Then there’s the ingenious mixing of strophic, seemingly artless, folk-like songs (in which the same or similar music is repeated, verse by verse – as in the opening song, “Das Wandern”) with much more dramatically volatile through-composed settings, such as “Eifersucht und Stolz”. However, what chiefly gives Die Schöne Müllerin its aura of total mastery is the powerful sense of music simultaneously penetrating, revealing, enriching, and fusing with the poetry it sets.

Of course, being regarded as a masterpiece may not be altogether beneficial for any musical composition – least of all one that portrays such a combustible mixture of youthful impulsiveness, implacable fate and brutally crushed hopes. At times in the past, and certainly in the mid-20th century, there was a noticeable tendency for interpreters to treat the cycle too reverentially, like a priceless museum-piece, rather than engaging robustly with its searing emotions. That is a mistake. It’s true that the Schubert who wrote Die Schöne Müllerin had just experienced a shocking intimation of his own mortality. But it was a shock that intensified rather than sapped his creative impetus. He was still a young man. He still yearned for life – and that shines through this music. These songs lose all their energy if wrapped in a funereal shroud of sentimentality or quasi-religiosity.

There were certainly periods of respite and remission in Schubert’s remaining years. The summer of 1825, for instance, seems to have been an oasis of contentment, during which he wrote his most grandiose orchestral work, the “Great C Major” Symphony. But his life after 1823 was never the same. His close-knit circle of friends broke up, as contemporaries married or left Vienna. The bawdy revels ended. And his health worsened inexorably, with continual chronic headaches and long periods when he couldn’t leave his house. He never stopped working. Touchingly, in his last significant work, “Der Hirt auf dem

Felsen” (The Shepherd on the Rock), completed a month before he died on 19th November 1828, he returned to the bitter-sweet poetic world of Wilhelm Müller. But it’s hard not to feel that, with the composition of Die Schöne Müllerin , Schubert’s own winter’s journey had begun.

JAMES GILCHRIST

James Gilchrist began his working life as a doctor, turning to a full-time music career in 1996.

Concert appearances include Britten Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (Manchester Camerata, Douglas Boyd), Haydn The Seasons (BBC Proms, St Louis Symphony, Sir Roger Norrington), Tippett The Knot Garden (BBCSO, Sir Andrew Davis), Bach Christmas Oratorio (Tonhalle-Orchestra Zurich, Ton Koopman), Bach St Matthew Passion (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Sir Roger Norrington), Handel Belshazzar (Philharmonia Baroque, Nicholas McGegan), Stravinsky La Pulcinella (Orchestre National de Paris, Thierry Fischer) and Handel Athalia (Concerto Köln, Ivor Bolton).

As a recitalist, he has appeared at many venues throughout the UK, in New York, and at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. In his partnership with the pianist Anna Tilbrook his performances include many broadcasts for BBC Radio 3, performing Schumann cycles and Schubert songs, as well as demonstrating a special interest in English song, with broadcasts of Finzi, Vaughan Williams, Robin Holloway, Tippett and Britten. James is also partnered regularly by the harpist Alison Nicholls, with whom he has performed songs by the contemporary English composers Alec Roth, Howard Skempton (both recorded on Hyperion) and Nicola LeFanu.

Amongst his many recordings are the title role in Britten Albert Herring (Hickox), Bach St Matthew Passion (McCreesh), Bach Cantatas (Gardiner, Koopman and Suzuki), ‘Oh Fair to See'(the complete songs for Tenor and Piano by Gerald Finzi), Vaughan Williams On Wenlock Edge (finalist in the 2008 Gramophone awards) and Britten Owen Wingrave (Hickox). Recent and forthcoming releases include songs of

Lennox Berkeley (Chandos), Britten Winter Words and Leighton Earth, sweet Earth (Linn) and a ground-breaking new recording rediscovering the work of the early 20th century composer Muriel Herbert (Linn).

ANNA TILBROOK

Born in Hertfordshire, Anna Tilbrook studied music at York University and with Julius Drake at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where she was a major prize winner. She has quickly become one of Britain’s most exciting young pianists, with a considerable reputation in song recitals and chamber music, having made her debut at the Wigmore Hall in 1999. She has collaborated with such leading singers as James Gilchrist, Lucy Crowe, Sarah Tynan, Willard White, Barbara Bonney, Mark Padmore, Stephan Loges, Ian Bostridge and Gillian Keith. For Welsh National Opera she has accompanied Angela Gheorghiu, José Carreras and Bryn Terfel in televised concerts, and over several years has been associated with the Two Moors Festival in Devon, programming comprehensive surveys of the song cycles of Schubert, Schumann and Mahler. Enjoying partnerships with a number of instrumentalists, she has performed Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du Temps at St David’s Hall, Cardiff, and with the Fitzwilliam String Quartet has played chamber music by Shostakovich, a chamber arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto, KV 415 and Elgar’s Piano Quintet throughout the UK. Recently she has given recitals at LSO St Luke’s, the Three Choirs Festival, Oxford Lieder Festival, and the festivals Wratislavia Cantans in Wroc?aw and Anima Mundi in Pisa. In 2006 Anna Tilbrook made her conducting debut at the Buxton Festival directing Telemann’s Pimpinone from the harpsichord.

Gramophone Magazine:

Editor’s Choice

Classic FM Magazine:

Editor’s Choice

‘…one of the great recordings of Die Schöne Müllerin.’ (“Cherwell”, Oxford University)