Artist Led, Creatively Driven

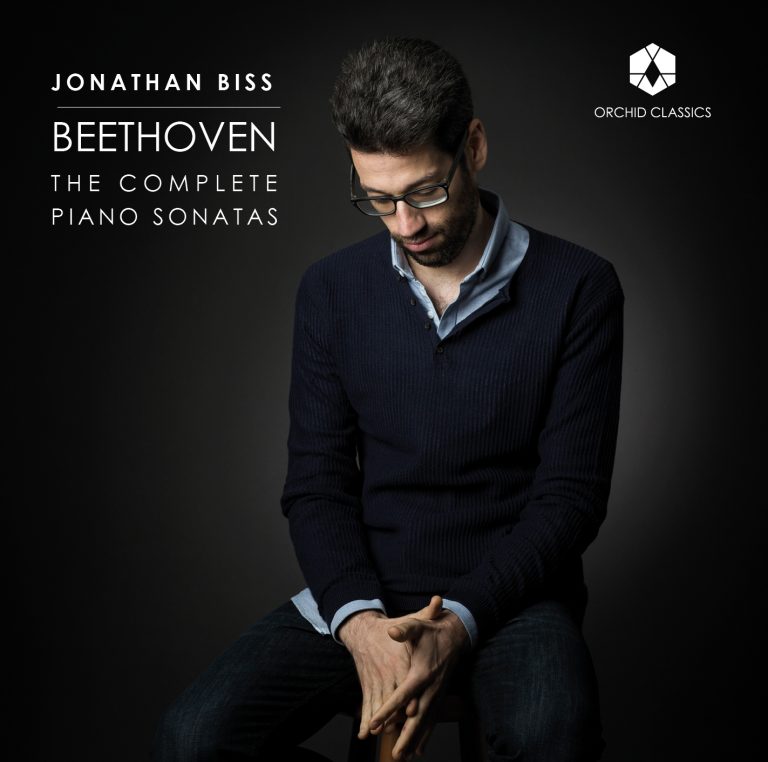

Jonathan Biss

Beethoven

Piano Sonatas vol.9

Release Date: November 1st 2019

ORC100109

PIANO SONATAS, Vol 9

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No.7 in D major, Op.10 No.3

1 Presto 6.32

2 Largo e mesto 7.48

3 Menuetto: Allegro 2.47

4 Rondo: Allegro 4.24

Piano Sonata No.18 in E flat major, Op.31 No.3

5 Allegro 8.17

6 Scherzo: Allegretto vivace 4.56

7 Menuetto: moderato e grazioso 3.35

8 Presto con fuoco 4.33

Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, Op.111

9 Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato 8.47

10 Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e cantabile 16.14

Total time 67.56

Jonathan Biss, piano

In my scores for each of the sonatas on this recording there are question marks.

I write almost nothing in my music; I never have. Not when I was young, to the consternation of my teachers, and not now, to the amusement and occasional irritation of my colleagues. My scores contain few fingerings, hardly any phrasing indications, virtually no written instructions. Somehow, the clarity and even inspiration I get from looking at the unblemished score outweighs the potential benefit of anything I might choose to add to it. And anyway, I tell myself, if it really matters to me, I won’t forget it.

This near absence of markings makes the presence of all those question marks all the more striking. It’s not just that these works are filled with questions; it’s that the questioning aspect is so central to their meaning. Playing these sonatas, I felt I could get by just fine without writing the words giocoso, or teneramente, or appassionato, even though they often apply, Lord knows; the question marks, on the other hand, felt indispensable.

This recording is about culminations: each of the three works is the last of a set of three; the album comes at the end of nine years of recording these sonatas; Op.111 is Beethoven’s farewell to the genre. And so it is a beautiful irony that these pieces feature so many more questions than they do answers – that they offer so much more uncertainty than certainty. It is especially fascinating given that this is Beethoven, of all people: a composer of unmatched inner conviction and intensity. And yet, ultimately, this music is as much about his vulnerability as it is about his strength.

Having said all of that, the work that opens this recording – the D major Sonata Op.10 No.3, one of the masterpieces of Beethoven’s early period – begins with a declarative statement; the questions will come later. This opening salvo, rising throughout and crackling with energy in the way that only Beethoven’s music can, acts as a launching pad for a movement that is altogether an irresistible force: unusually marked “Presto,” its momentum and almost reckless optimism are its dominant features. But even in this movement, brilliant and confident as it is, questioning will play a major role: there are passages where bar after bar, the upbeats are accented, rather than the downbeats. This goes on for such an uncomfortably long time, it eventually messes with our perception of the meter and, by extension, our perception of the passage of time.

The slow movement which follows doesn’t merely alter our perception of time: by its end, time itself stops. Its marking of “Largo e mesto” is just as atypical of Beethoven as was the firstmovement’s “Presto” – Beethoven wrote plenty of tragic music, but it was rare for him to make the sadness explicit inthe tempo indication, which should give a sense of just how extreme and overt this movement’s grief is. This sonata was written shortly before the Quartet Op.18 No.1, whose slow movement allegedly is meant to evoke the tomb scene from Romeo and Juliet. The two slow movements occupy a similar emotional space: where so much of Beethoven’s music is deeply emotional without being demonstrative, these slow movements are theatrical. The pain is real, but it is also being performed, with sighing appoggiaturas and violent outbursts not just conveying the music’s character, but telegraphing it. This movement is – as is always the case with Beethoven – powerful and immaculately wrought, but its affects do not feel as devastatingly personal as is the case with so many of his other slow movements. Still, by the time the movement comes to an end, with its long lines having largely broken down, and silence having become more prominent than sound, the effect is overpowering.

In the last movement of Op.10 No.3, the silences become even more frequent and more significant, and it is here that the music becomes a festival of questions. As thrilling and vibrant as the sonata has already been, it is this movement that is most totally original. Being a rondo, its main theme appears again and again, which only serves to underscore that it isn’t really a “theme” at all: it is a three note query, pointed upward, like all questions, ending in irresolution and followed by a silence that is much longer than it is. In this movement, Beethoven manages to be simultaneously good-natured and extremely mysterious, and the latter quality becomes more and more prominent as these questions accumulate. It is one of Beethoven’s most imaginative solutions to the problem of what sort of a movementshould end a sonata, and its final moments – with the left hand playing different versions of the three note figure again and again, as the right glides weightlessly up and down the keyboard – are as moving as they are witty.

If Op.10 No.3’s questions took a while to appear, in the Sonata Op.31 No.3, they arrive instantly – in the first measure of the first movement. It is difficult to convey, from the vantage point of 2019, and after Schubert and Brahms and Stravinsky and Xenakis and all the rest, just what a bold move it was for Beethoven to do this in 1802: to begin a work not with an assertive announcement of its tonality, but with a falling – sighing – fifth, harmonically away from home. This opening conveys such a sense of vulnerability, it was co-opted by none other than Robert Schumann – the philosopher-king of musical vulnerability – for the opening of his A major String Quartet. Beethoven was often the most single-minded – some might say bloody-minded – of composers, sticking with one idea, one character, one mood, for minutes on end. But in this movement, the fragility of the opening is in constant dialogue with music that is spirited and playful. This slightly uncharacteristic meeting of unlike musics launches a sonata that finds Beethoven experimenting again and again: a scherzo that would not sound out of place in a Mozart opera, a courtly, nostalgic menuetto that stands in for a true slow movement, a finale that evokes a hunt. Op.31 No.3 comes near the start of Beethoven’s middle period, and the questions are not only in the music itself: after having mastered one version of the form in his early period, Beethoven is now questioning what a sonata can be.

From that point on, Beethoven would provide a different, usually stunning answer to the question each time he wrote a piano sonata; Op.111, his final essay in the form and thus his final answer to that question, is as astonishing – as unfathomable – today as it was in 1822. The shy, halting query that opens Op.31 No.3 was already a significant departure from classical norms; the enraged one that launches Op.111 far from any harmonic home and sets it on its harrowing course is one of the most unsettling moments in all of music. Op.111 has just two movements – the idea of something following the second would be unthinkable – and the two are a clash of opposites. The first is dominated by rigour, concision, rage, harmonic tension, propulsion, and hopelessness; the second, by spaciousness, consolation, consonance, a freewheeling improvisatory quality, and, above all, wonder. This set of variations covers a massive amount of emotional and psychological territory – it ranges from absolute serenity to an overwhelming, questing intensity – but throughout, it regards the universe with the widest of eyes.

Op.111 is the end – the end of Beethoven’s journey with the piano sonata, his last word on the genre he upended and in which he was most prolific – and therefore one of the strangest and most remarkable things about it is its inability to end. Its theme has an open-ended, inconclusive quality, which always makes the next variation, and the next, and the next – each more restless than the one before – seem inevitable. When this progression from the calm to the wild reaches an improbably jazz-inflected extreme, and yet still cannot resolve, Beethoven searches for closure in other ways, mining the nether regions of the piano, and the stratospheric end, in alternation. When this brings him no closer to a point of rest, he travels further still, to a distant E flat major oasis that chafes and bristles and struggles against the limitations of the piano, against its refusal to make a sound that sings and carries and lives forever…

The desire to live forever, and the impossibility of living forever, is really the subtext of this movement, and of Beethoven’s enormous difficultyin ending it. And it is the only explanation for why this movement – the longest and in some ways most monumental of Beethoven’s sonata movements – ends not with certainty, not with an affirmation, but with an evaporation into thin air. Not a question, precisely, but one final expression of vulnerability and doubt. My feeling has always been (and always will be, I suspect) that this ending is a death – a heartbeat that simply stops. No one will ever know if this was Beethoven’s intention. But it is, beyond all argument, a commentary on the unknowability of the universe. It is somehow both humbling and reassuringto know that Beethoven was as uncertain of his place in it as the rest of us are. His ability to communicate that uncertainty is perhaps the greatest of all the gifts he left us.

© Jonathan Biss

Jonathan Biss

Pianist Jonathan Biss’s approach to music is a holistic one. In his own words: I’m trying to pursue as broad a definition as possible of what it means to be a musician. As well as being one of the world’s most sought-after pianists, a regular performer with major orchestras, concert halls and festivals around the globe and co-Artistic Director of Marlboro Music, Jonathan Biss is also a renowned teacher, writer and musical thinker.

His deep musical curiosity has led him to explore music in a multi-faceted way. Through concerts, teaching, writing and commissioning, he fully immerses himself in projects close to his heart, including Late Style, an exploration of the stylistic changes typical of composers – Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Britten, Elgar, Gesualdo, Kurtág, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann – as they approached the end of life, looked at through solo and chamber music performances, masterclasses and a Kindle Single publication Coda; and Schumann: Under the Influence a 30-concert initiative examining the work of Robert Schumann and the musical influences on him, with a related Kindle publication A Pianist Under the Influence.

This 360° approach reaches its zenith with Biss and Beethoven. In 2011, he embarked on a nine-year, nine-album project to record the complete cycle of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. Starting in September 2019, in the lead-up to the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth in December 2020, he will perform a whole season focused around Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, with more than 50 recitals worldwide. This includes performing the complete sonatas at Wigmore Hall and Berkeley, multi-concert-series in Washington, Philadelphia, and Seattle, as well as recitals in Rome, Budapest, New York and Sydney.

One of the great Beethoven interpreters of our time, Biss’s fascination with Beethoven dates back to childhood and Beethoven’s music has been a constant throughout his life. In 2011 Biss released Beethoven’s Shadow, the first Kindle eBook to be written by a classical musician. He has subsequently launched Exploring Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, Coursera’s online learning course that has reached more than 150,000 subscribers worldwide; and initiated Beethoven/5,a project to commission five piano concertos as companion works for each of Beethoven’s piano concertos from composers TimoAndres, Sally Beamish, Salvatore Sciarrino, Caroline Shaw and Brett Dean. The latter will be premiered in February 2020 with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and subsequently performed by orchestras in USA, Germany, France, Poland and Australia.

As one of the first recipients of the Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award in 2003, Biss has a long-standing relationship with Mitsuko Uchida with whom he now enjoys the prestigious position of Co-Artistic Director of Marlboro Music. Marlboro holds a special place for Biss, who spent twelve summers there, and for whom nurturing the next generation of musicians is vitally important. Bisscontinues his teaching as Neubauer Family Chair in Piano Studies at Curtis Institute of Music.

Biss is no stranger to the world’s great stages. He has performed with major orchestras across the US and Europe, including New York Philharmonic, LA Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, CBSO, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Concertgebouw. He has appeared at the Salzburg and Lucerne Festivals, has made several appearances at Wigmore Hall and Carnegie Hall, and is in demand as a chamber musician.

He was the first American to be named a BBC New Generation Artist, and has been recognised with many other awards including the Leonard Bernstein Award presented at the 2005 Schleswig-Holstein Festival, Wolf Trap’s Shouse Debut Artist Award, the Andrew Wolf Memorial Chamber Music Award, Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award, an Avery Fisher Career Grant, the 2003 Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award, and the 2002 Gilmore Young Artist Award.

Surrounded by music from an early age, Jonathan Biss is the son of violist and violinist Paul Biss and violinist Miriam Fried, and grandson of cellist Raya Garbousova (for whom Samuel Barber composed his cello concerto). He studied with Leon Fleisher at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, and gave his New York recital debut aged 20.