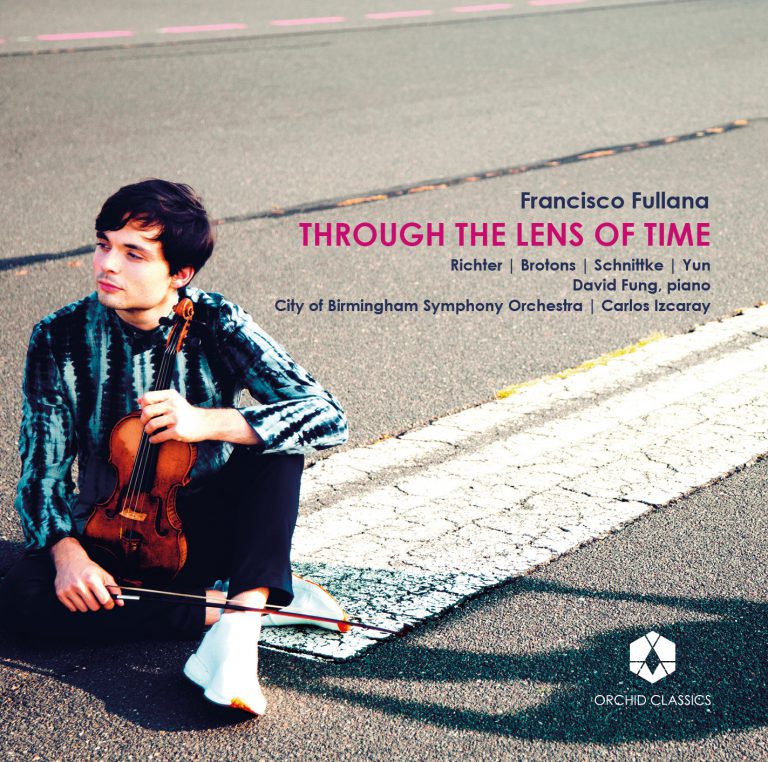

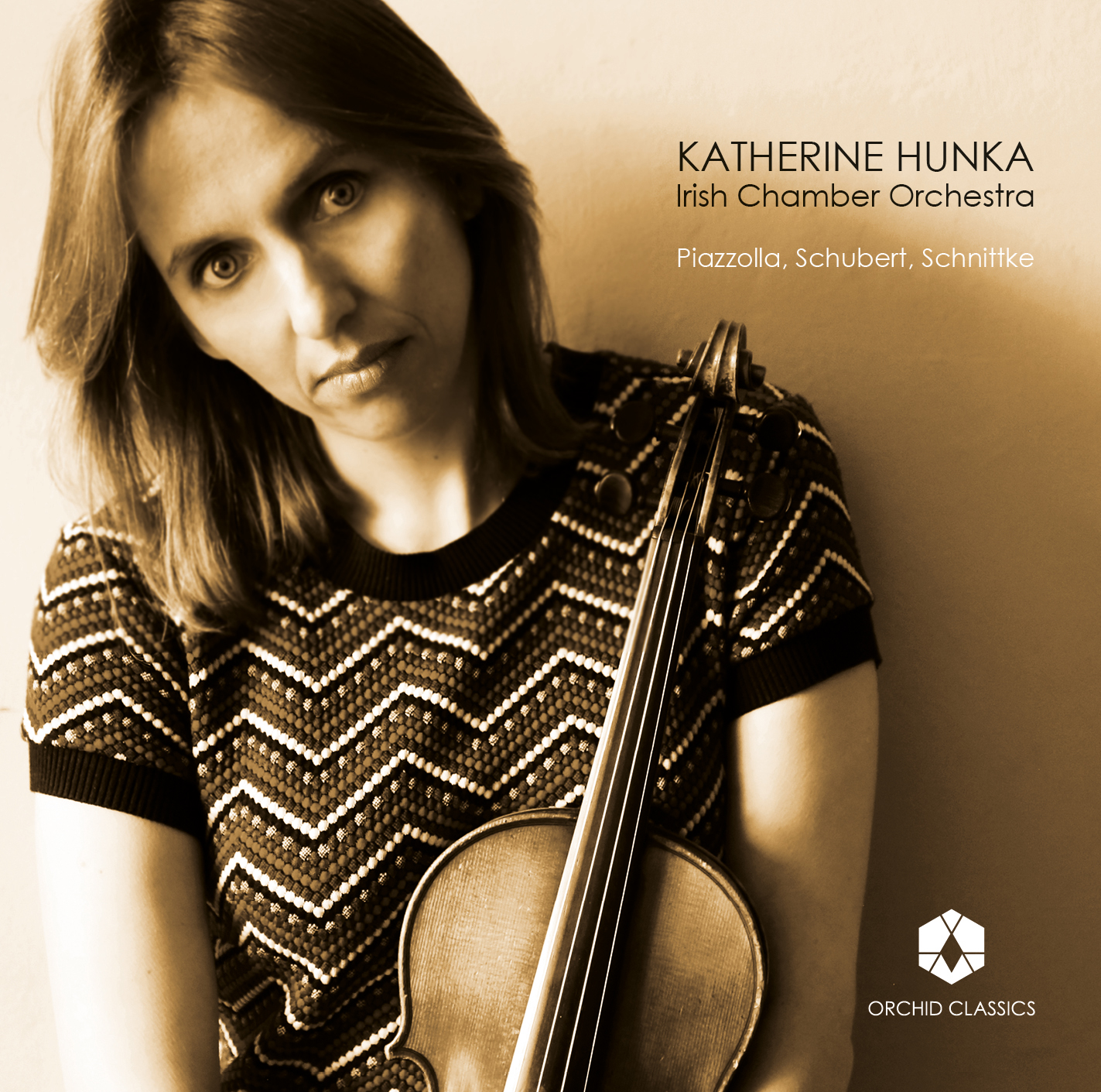

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Piazzolla, Schubert, Schnittke

Irish Chamber Orchestra / Katherine Hunka

Release Date: April 17th 2020

ORC100130

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992)

The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires (Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas)

(arr. L. Desyatnikov for violin and strings)

1 Otoño Porteño (Autumn) 6.56

2 Invierno Porteño (Winter) 7.08

3 Primavera Porteña (Spring) 6.00

4 Verano Porteño (Summer) 6.12

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

5 Rondo in A major for violin andstring orchestra D438 14.48

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998)

6 Moz-Art à la Haydn 12.12

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992)

7 Oblivion 4.43

Total time 58.02

Katherine Hunka, violin/director

Nicola Sweeney, violin (Schnittke)

Irish Chamber Orchestra

The devices of fusion and allusion are integral to the musical styles of both Astor Piazzolla and Alfred Schnittke, even if the results inhabit very different soundworlds. Piazzolla fused the Argentine tango with Western classical techniques, while Schnittke frequently produced aural collages including postmodern allusions to the music of the past. Both wrote music that captured something of the human spirit; a sense of energy and tragicomedy that will often have a visceral effect on the listener. This spirited quality is one that Piazzolla and Schnittke share with Schubert, whose life fizzed brightly before being prematurely extinguished, leaving behind an extraordinary musical legacy.

Piazzolla was born in Buenos Aires before moving with his family to New York in 1924, escaping Argentina’s economic crisis and settling in the cultural melting pot that was Greenwich Village, where Astor’s father, Vincent, ran a barber’s shop. A few years after settling in, Vincent gave Astor a present for his eighth birthday: a bandonéon that he’d picked up in a pawn shop. Initially more interested in listening to Bach and jazz than playing the instrument, Astor started practising to please his father, but soon became proficient. Meanwhile, Vincent reminisced about their homeland by listening to tangos, and within a few years the teenage Astor had formed a friendship with the influential Argentine musician Carlos Gardel, for whom he started to work as a performer, translator and tour guide. All the ingredients were in place for what would become Piazzolla’s unique compositional style, reflecting the rich combination of influences to which he was exposedat a young age.

Piazzolla moved back to Buenos Aires in 1937, making tango arrangements alongside his classical music studies with Ginastera. In 1954, a symphony he’d written for the Buenos Aires Philharmonic Orchestra won him a scholarship to study in Paris with the great Nadia Boulanger, who encouraged him to be true to his love of tango. This period of study lasted for about 18 months, but so profound was Boulanger’s influence on Piazzolla that he said the growth he’d experienced felt more like “eighteen years”. Back in Buenos Aires, he developed the ‘nuevo tango’ style, blending chromaticism, jazz, fugal textures and dissonance, successfully offending traditionalists in both the classical music and tango worlds. Eventually Piazzolla settled in Paris in 1974, and by the 1980s his music was widely appreciated in his homeland and across the world.

Piazzolla did not conceive Las Cuatro Estaciones Porteñas (‘The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires’) as a suite. Verano Porteño (‘Summer’), alert and enigmatic, was composed first, in 1965, as incidental music to accompany Alberto Rodríguez Muñoz’s play, Melenita de Oro. Piazzolla then arranged this movement for his mentor Aníbal Troilo’s traditional tango orchestra, which recorded the piece in 1967. The blustery Otoño (‘Autumn’) followed in 1969, with the jittery liveliness of Primavera (‘Spring’) and a gently melancholic Invierno (‘Winter’) completed in 1970. We hear the four pieces in a recomposition for violin and strings made by Leonid Desyatnikov between 1996 and 1998, in which he playfully incorporates elements from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons into Piazzolla’s music. Piazzolla’s Estaciones were popularised by Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer, for whom Schnittke also wrote works such as his Concerto Grosso No.1.

Schubert composed his Rondo in A, D438, in June 1816, when he was still in his late teens and a few years into his studies with Antonio Salieri. His fellow Salieri student, Anselm Hüttenbrenner, described the 18-year-old Schubert:

“Schubert’s outward appearance was anything but striking or prepossessing. He was short of stature, with a full, round face, and was rather stout. His forehead was very beautifully domed. Because of his short-sightedness he always wore spectacles, which he did not take off even during sleep. Dress was a thing in which he took no interest whatever … and listening to flattering talk about himself he found downright nauseating.”

1816 was also the year in which Schubert had become particularly engrossed in the music of Mozart, which influenced much of his output at the time including the Symphony No.5, orchestrated for a pared-down, Mozartian ensemble, and this graceful Rondo. The 19-year-old Schubert wrote in his diary:

“A light, bright, fine day this will remain, for the rest of my life. As from afar the magic notes of Mozart’s music still gently haunt me… The soul retains these lovely experiences, which no time, no circumstances can erase… they lighten our existence. They show us in the darkness of this life a bright, clear, beautiful horizon, for which we hope with confidence. Oh Mozart, immortal Mozart, how many, oh how many invaluable experiences of a better, more radiant life have you brought into our souls?”

Despite his love of Mozart and Beethoven, and his prolific output, Schubert did not compose any concertos for solo instrument and orchestra; this Rondo is the closest thing we have, along with the Konzertstück, D345, also for violin and orchestra. Schubert may have intended the Rondo’s solo violin part for himself or his brother, Ferdinand, both of whom had learned the violin at a young age. The work was never published during Schubert’s lifetime, but was eventually issued in 1897 by Breitkopf und Härtel. It begins with an elegant, leisurely Adagio introduction. The virtuosic Rondo that follows shows the influence of Mozart’s violin concertos, especially their finales, and incorporates three main themes: a lively, dancing opening melody, a folk-like theme, and dramatic material shifting between major and minor keys.

Born to German-speaking parents in what is now Latvia, Schnittke grew up in Russia speaking German. Schnittke began his musical studies in Vienna when his father began working for a Soviet newspaper there in 1946. This exposure to Austro-German styles had a lasting impact: “I felt every moment there to be a link of the historical chain: all was multi-dimensional; the past represented a world of ever-present ghosts, and I was not a barbarian without any connections, but the conscious bearer of the task in my life.”

The family returned to Russia in 1948, and Schnittke studied at the Music College of the October Revolution, which has since been renamed in his honour, before attending the Moscow Conservatory, graduating in 1961. He then started teaching instrumentation at the Conservatory and working as a freelance composer. Schnittke’s freedom to travel outside the Soviet Union was severely restricted, and although he received numerous official commissions, ultimately his music was deemed too experimental and he fell out of favour.

During the Khrushchev era, Schnittke was able to view hitherto forbidden Western scores, including music by Stravinsky, Stockhausen, Nono, Ligeti, Webern, Schoenberg and Berg. The impact was profound, but he also embraced a plethora of other influences; his self-coined “polystylistics” explored medieval plainchant, Renaissance polyphony, Baroque figuration, the Classical sonata, the Viennese waltz, late-Romantic orchestration, 12-tone principles, aleatory methods, and pop. Schnittke explained:

“My musical development took a course similar to that of some friends and colleagues, across piano concerto romanticism, neoclassic academicism, and attempts at eclectic synthesis… Having arrived at the final station, I decided to get off the already crowded train. Since then I have tried to proceed on foot.”

In works such as Moz-Art à la Haydn (1977) and A Paganini (1982), Schnittke humorously parodied earlier composers as well as paying tribute to them. Moz-Art à la Haydn combines an unfinished fragment by Mozart, his ‘Pantomime Music’, K446, with the theatricality of Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony, No.45, in the finale of which the performers leave the stage one by one, hinting to their patron, Prince Esterházy, that they need a holiday. Schnittke begins Moz-Art à la Haydn in complete darkness, with the musicians improvising on the Mozart fragment. The light comes on at a tremolo diminished chord.

To capture the visual, staged aspects of this piece, the Irish Chamber Orchestra worked with producer Andrew Keener to communicate the work’s theatricality through audible movement and effects. When the musicians shift positions from a traditional ensemble formation to something more unconventional, we hear them making a great kerfuffle as they move about, running across the stage, dropping things, mumbling and chattering. Their return to their original formationis even more rapid – chaos ensues. During moments of mock tragedy, the artists were asked to pretend to cry; Keener demonstrated how this should sound and was so good at it that his wailing is used on the final recording.

Dating from 1982, Oblivion is one of Piazzolla’s most celebrated, and most traditional, tangos, made famous in part by its use in the Marco Bellochio film, Henry IV (1984). There is a gentle, almost minimalistic introduction from the ensemble, before the violin enters with its bittersweet theme. After a more passionate central section, the mainmelody returns, fading to an enigmatic close.

© Joanna Wyld, 2020

Katherine Hunka

Born in London, Katherine Hunka grew up under the musical guidance of teacher Sheila Nelson, she performed chamber music at London’s South Bank and the Royal Albert hall, was soloist with the City of London Sinfonia and led the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. Katherine was awarded a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music where she studied with with Gyorgy Pauk, and then furthered her studies in the USA at Indiana University where she also acted as teaching assistant to her professor, Mauricio Fuks. This instilled in her a great love of teaching. She has since returned to Indiana as a guest Professor and been made a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music.

Katherine has been Leader of the Irish Chamber Orchestra since 2002 and regularly directs from the leader’s chair. As director and soloist, with the ICO, she has toured Germany, China and Singapore, appeared at the West Cork Chamber Music Festival, and more recently, at the Kilkenny Arts Festival.

Katherine directs ICO national tours, which take the orchestra all over Ireland and enjoys collaboration with contemporary composers. She has directed premieres with many Irish composers. As leader, she has also enjoyed performing solo concertos and chamber music with Jörg Widmann, Pekka Kuusisto, Anthony Marwood and Nigel Kennedy amongst others.

Katherine performs regularly, as a chamber musician and soloist, at festivals throughout Ireland and the UK. At the Aldeburgh Festival she premiered Benjamin Britten’s rediscovered Double Concerto. She has been a regular at the West Cork Chamber Music Festival and the Killaloe festival. Her trio Far Flung, with accordionist Dermot Dunne and bassist Malachy Robinson, delights audiences with its light-hearted approach, their repertoire spans from Bach to Klezmer with anything in between. They have recently released their first album.

Katherine has been a guest leader with the Manchester Camerata, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. She has also been guest soloist with the RTE National Symphony Orchestra and Concert Orchestra.

She is currently a Professor at the CIT Cork School of Music and the Irish World Academy of Music. She plays a Grancino violin and her bows are made by Gary Leahy.

Irish Chamber Orchestra

The Irish Chamber Orchestra is Ireland’s most dynamic ensemble. Mixing traditional repertoire with new commissions, and collaborating with everyone from DJs to dance companies, the ICO pushes the boundaries of what a chamber orchestra can do. You are as likely to find the ICO at Electric Picnic as Mozartfest, but wherever it performs, the ICO delivers world-class concerts feted for its energy and style.

Each year, the ICO presents concert seasons in both Limerick and Dublin, embarks on two national tours, and makes a number of prestigious international appearances. Its Artistic Committee works closely with Jörg Widmann, Principal Conductor/Artistic Partner, and Katherine Hunka, Leader, to devise exciting, diverse and innovative programmes, mixing standard repertoire with new work– often specially commissioned – from the best young Irish composers. This versatile approach enables it to appeal to music fans of every stripe while upholding the highest artistic standards.

Its groundbreaking initiative, Sing Out with Strings (SOWS), offers primary school children the chance to learn music and continue with the ICO Youth Orchestra, designed for aspiring teenage musicians.

The ICO supports the MA in Classical String Performance at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance at the University of Limerick, and is funded by The Arts Council of Ireland/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

DOUBLE FIVE STARS

‘The lyrical cool of Oblivion has rarely sounded so achingly cool…

…an exceptional release.’

BBC Music Magazine

Pick of the Week

The Guardian

‘The ensemble is so tight, but the results have such spontaneity. How can you not smile at the descending plucked bassline at the slow centre of “Winter”? The cheeky nod to a ubiquitous canon which ends the section never sounds arch. A blast.’

The Arts Desk

‘a phenomenal album’

Crescendo

‘Hunka’s pure tone and silky, insouciant legato phrasing are beguiling’

MusicWeb International