Artist Led, Creatively Driven

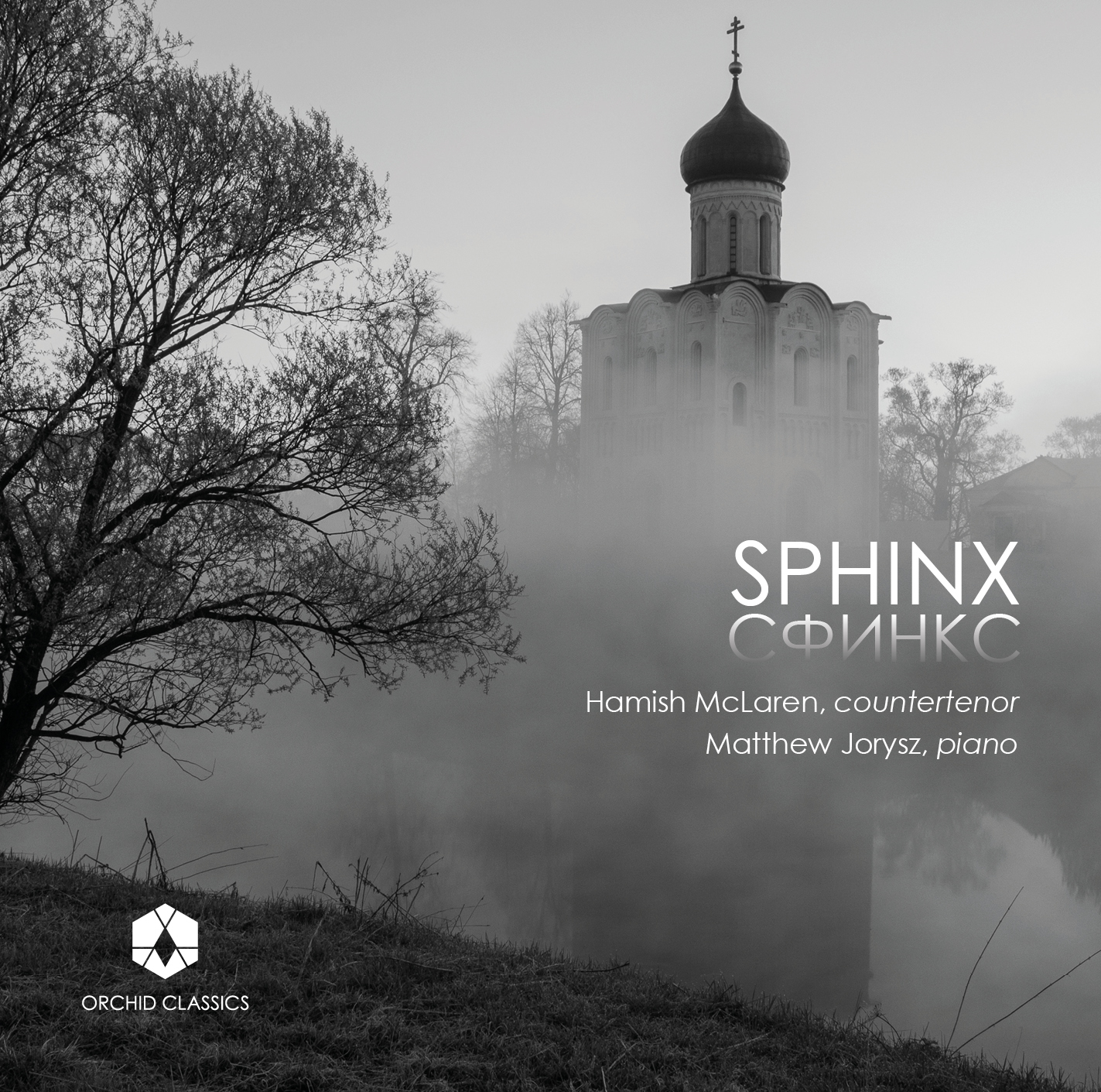

SPHINX

Hamish McLaren, countertenor

Matthew Jorysz, piano

Nathalie Green-Buckley, viola

Claudia Fuller, violin

Ben Michaels, cello

Release Date: 7th May

ORC100161

Boris Tchaikovsky (1925-1996)

From Kipling

1. The Distant Amazon

2. Homer

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Two Romances to Poems by Lermontov, Op.84

3. II Morning in the Caucasus

4. I Ballad

Alexander Borodin (1833-1887)

5. My songs are full of poison

6. For the distant shores of your native country

Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915)

7. Five Romances to poems by Y. Polonsky: A Night in the Scottish Highlands, Op.33 No.1

8. Ten Poems from Ellis’ Collection “Immortals”: Stalactites, Op.26 No.8

Boris Tchaikovsky

Two Poems by Lermontov

9. Autumn

10. The Pine

Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950)

11. Twelve Songs by Bal’mont: The Albatross, Op.2 No.8*

Dmitri Shostakovich

Spanish Songs, Op.100

12. I Farewell, Granada!

13. II The Little Stars

14. III The First Meeting

15. IV Ronda

16. V Dark-Eyed Girl

17. VI Dream (Barcarolle)

18. Desdemona’s Romance (Willow Song)*

19. A pointless gift, a chance gift*

Elena Firsova (b.1950)

Two Songs to Poems by Boris Pasternak

20. The Wind*

21. Twilight*

Nikolai Myaskovsky

22. Twelve Songs by Bal’mont: The Sphinx, Op.2 No.11*

Elena Firsova

23. Winter Elegy, Op.91*

*World Premiere Recording

Russia’s rich tradition of art song was rooted in the genteel drawing-room and salon culture of the early 19th century. Gradually these modest lyrical “romances” set their sights higher to embrace dramatic and philosophical themes, but never lost their intimacy and their ties to the treasured lines of favourite poets. This selection explores some fascinating, but less-trodden paths through this repertoire, inspired principally by the theme of distant lands. Dreams of travel, romantic landscapes, love and loss, and ruminations on life and death – these motifs appeared at the height of Imperial Russia, and their appeal endured even amidst the paroxysms of Stalin’s rule. In this recital, Alexander Borodin (1833-1887), a celebrated chemistry professor and part-time composer from St Petersburg meets Sergei Taneyev (1856-1915), a formidable Moscow professor of composition from the next generation; Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) stands alongside another major symphonist, his Moscow colleague Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950), and Shostakovich’s student Boris Tchaikovsky (1925-1996), a prodigy widely known for his film music, passes the baton to Elena Firsova, a post-Soviet émigré to England and a distinctive lyrical voice of today.

Boris Tchaikovsky’s two romances From Kipling (1994) are among his last pieces – he had planned a full song cycle but did not live to complete the project. The texts may be humorous, but Tchaikovsky’s settings lend them a thoughtful and melancholy colouring, prompting us to look for other possible meanings. The text of the The Distant Amazon was already well known to the Soviet public thanks to Samuil Marshak’s catchy translation which had been set as a jolly little ditty with great popular appeal. The ditty appealed to the keen thirst for travel to distant lands prevalent among Soviet citizens, even if the prospects of quenching that thirst were zero for most of them, and so the poem had already acquired a bitter-sweet flavour. In Tchaikovsky’s affecting duet between the voice and solo viola we may also sense the narrowing of options as we move towards the end of our lives. The song Homer has an even more personal ring to it as it describes a poet (or the composer) who can only retell old tales, but manages to do so in an amusing manner, so much so that the public is content. Transparent harmonics in the viola are used to evoke a mysterious and distant past, while also inviting us to take the song in earnest, perhaps even as an artistic credo.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s music of the early 1950s divides sharply into public and private works: in those dark, paranoid years of late Stalinism it was prudent to release only those pieces that were optimistic and easy on the ear. These two settings of texts by Lermontov belonged emphatically to the “private” category. In both songs Shostakovich engages with the traditions of 19th century art song on his own terms. The general shapes of musical phrases and textures may look reassuringly familiar on the page – like the piano accompaniment in the Ballad which seems to depict the waves – but the harmony is elusive and ever-shifting, while the atmosphere is decidedly morose. Morning in the Caucasus is a shade brighter, but it refuses to settle on the main major chord for more than a fleeting moment. If Shostakovich had given these songs a premiere at the time, the critics would have castigated him for indulging again in artistic “formalism”. In the event, the songs were left unpublished until they were found among Shostakovich’s papers after his death.

These two songs by Alexander Borodin became instant Russian musical classics as soon as he had written them. The prolific critic Vladimir Stasov steered the “Mighty Handful” group of composers towards original national art, and he was wildly enthusiastic on hearing these songs. Borodin’s admiration for Robert Schumann can be detected in both, but he has absorbed and personalised the older composer’s language. The bitterness of Heine’s text elicits a striking harmonic turn in the middle of My Songs are Full of Poison (1868), a pivot which abruptly removes the song from the genre of Russian domestic or salon songs. In For the Distant Shores (1881), a Pushkin setting, Borodin masterfully conveys the poem’s burning sense of loss. The vocal line is austere at times, as if choking back tears, but the piano colours it with myriad shades of emotion subtly implying what we are not explicitly told in the words.

Sergei Taneyev belongs to the following generation of Russian composers and takes the art of Russian song to a further level of sophistication. Yakov Polonsky’s poem A Night in the Scottish Highlands portrays an enigmatic landscape full of mysterious echoes, echoes which Taneyev enhances with vivid word painting. The piano imitates the sweet plucking of a lute, or the brazen vigour of a horn call, and in one passage it even manages to convey the image of rocks tumbling over a precipice. Beyond these vivid pictorial elements, the music, striving and nearly ecstatic, is powerfully persuasive on its own terms. By contrast, the grief of Stalactites seems to take Borodin’s “Distant Shores” a step further. The stalactites, symbolising eternal “frozen” tears, are represented in the piano part through a repeated chordal figure, ever present and always gently falling. The vocal part presents a contrasting melody and at times both the musicians fall into the gravitational pull of one recurring motive. The ever-changing combinations of melodic elements remind us that Taneyev was the foremost master of counterpoint in his time, and he could work out these complexities with the art that conceals art.

We return to Boris Tchaikovsky, and a selection of his Lermontov settings. Tchaikovsky approaches this poet in a vastly different manner to Shostakovich, and he sets the words in a fluent, melodic manner that reflects the sing-song style of the verses, particularly in Autumn. These songs are the work of a young prodigy still searching for a personal voice at the age of fifteen. The Pine is one of Lermontov’s most celebrated poems and it had been set by many composers in the past. This daunting artistic precedent spurred Tchaikovsky to bolder invention, and he plays deftly with shifting musical metres, producing a song that is both distinctive and delightful, earning a secure place among the other settings of the poem.

Nikolai Myaskovsky’s Albatross comes from his youthful collection of songs on the words by Konstantin Balmont. Balmont was a Symbolist poet, but he held back from the more extreme opacity of the movement. This made him a Symbolist congenial to composers, who could approach his imagery with confidence. Myaskovsky captures the rhythm of the gently rocking ocean waves in the piano part, while the albatross soars and glides in the rising phrases of the voice. It is a mesmerising landscape, unveiled through hauntingly gloomy harmonies. But change is afoot: as the poet finds power and freedom in solitude, the mood brightens and intensifies. It is tempting to see the song as a reflection of Myaskovsky’s own doleful and hermetic character.

If Shostakovich’s Spanish Songs seem to lack any of the composer’s characteristics, there is a simple reason for that: they are essentially arrangements of Spanish melodies he was given by the contralto Zara Dolukhanova. She had recently been one of the performers in the premiere of Shostakovich’s From Jewish Folk Poetry, and she most likely expected the composer to do something equally idiosyncratic with the Spanish material. But his treatment of the songs was self-effacing, with a lightly scored and sympathetic piano accompaniment. Dolukhanova premiered them with Shostakovich, but lost interest in them afterwards. Many other singers, however, were delighted with the songs and the Soviet critics where pleased that Shostakovich had produced such simple and accessible “people’s music”. If anything, we can detect Shostakovich in the economy of the writing, where other composers preferred to treat Spanish themes in a lush and extravagant manner.

The next two songs by Shostakovich were only discovered recently. These were off cuts from the score for the film Belinsky (1950) by the distinguished director Grigory Kozintsev. A Pointless Gift is a pastiche of early 19th century drawing-room songs, while Desdemona’s Romance is more individual (and quite possibly stemmed from an abandoned project of incidental music for Othello). It is hard to imagine that anyone could deride this song as “formalist gimmickry”, but that was the phrase used when the materials for the film were presented to the Ministry of Cinematography. At this point, Shostakovich was still under the cloud of being denounced for the complexity of his music two years earlier, so such a complaint meant that the composer was in no position to defend the song, and it was cut.

Elena Firsova made her name in the closing years of the Soviet Union, but she has lived and worked in Britain since the early 1990s. She is represented here by her settings of two contrasting poems by Boris Pasternak. The first of these, The Wind comes from the novel Doctor Zhivago, where it appears as if it is the work of the protagonist. It is a greeting to the beloved from beyond the grave, simple and stark, and Firsova responds to this simplicity by using that traditional musical symbol of death, the medieval chant Dies irae. Twilight comes from 1909, at the beginning of Pasternak’s career, and it belongs firmly to the Symbolist movement that dominated Russian literature at the time. Its meaning is quite opaque, although some medieval references may remind us of scenes from a pre-Raphaelite painting, and the poem’s beauty lies in the music of its alliterations. To match these delicate word patterns, Firsova provides equally enticing and refined harmonies and has the singer deliver the lines in a declamatory fashion, closely following their shifting poetic rhythms and matching the intensity of the music to the poetic images.

Balmont’s poem Sphinx, set by Myaskovsky, takes a Symbolist theme from ancient Egypt but concentrates concretely on the grandiosity of the immense sculpture and the cruel treatment of the slaves who toiled to build it, leaving a record of their suffering that has endured for over four thousand years. The song starts with enigmatic music drawn from Russian portrayals of the supernatural and continues as a darkly dramatic monologue.

The final track is Firsova’s Winter Elegy (for countertenor and string trio), a song bordering on a solo cantata. It is a setting of one of Pushkin’s most famous poems, loved by generations of Russians for its mixture of philosophy and lyricism, with a touch of wry humour. Firsova’s deft word-painting follows the progress of the poem sympathetically, resolving in the sweetly pained ethereal sounds that seem to grant the poet his desire to escape.

Professor Marina Frolova-Walker FBA

Hamish McLaren

Countertenor

Hamish studied history at St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he also sang as a choral scholar. From 2016 to 2019 he studied vocal performance at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Hamish developed a passion for Russian culture as a teenager and studied Russian while at school. One of his first opera roles at university was – incongruously enough – as the petulant social climbing Vava in Shostakovich’s hilarious operetta Cheryomushki Moskva. While at music college Hamish was fortunate enough to be taught Russian song by Ludmilla Andrew, and it was in the library of the Royal Academy of Music that Hamish first encountered the songs of Taneyev, Myaskovsky, and Firsova. Exhilarated by these songs, Hamish travelled to Russia in the summer of 2018, and there he combed through music shops from St Petersburg, to Moscow, and onto remote Irkutsk in Siberia. Many of the songs featured on this CD were brought back from this trip, including the two hitherto unrecorded film songs by Shostakovich.

Upon graduating from the Royal Academy of Music Hamish has launched a career as a freelance singer. He has toured South America, Europe and Russia with the Monteverdi Choir under the baton of John Eliot Gardiner, and he has performed on stage for British Youth Opera, the Royal Academy of Opera and Hampstead Garden Opera amongst others. Future engagements include performances for Opera Settecento and English Touring Opera.

Matthew Jorysz

Piano

Matthew Jorysz studied at Clare College, Cambridge, where he read music and held the Organ Scholarship. After graduating, he moved to London where he has held the post of Assistant Organist at Westminster Abbey since 2016. His work as an organist has seen tours of Europe and the USA, broadcasts on BBC Radio and television and several recordings, most notably of Duruflé’s Requiem with Neal Davies and Jennifer Johnston.

Alongside this, he works as a pianist and chamber musician, chiefly collaborating with singers. Recent projects have included performances of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, Messiaen’s Poèmes pour Mi, Schumann’s Dichterliebe, Britten’s Winter Words and a series of Britten’s Canticles performed at Westminster Abbey.

Nathalie Green-Buckley

Viola

Nathalie, 25, gained her Masters with DipRAM from the Royal Academy of Music in July 2018 where she studied the viola with Martin Outram. Having been principal viola of the National Youth Orchestra, Nathalie went on to pursue further orchestral playing whilst she read Music at the University of Cambridge and was a player on the London Symphony Orchestra String Experience Scheme, performing with the orchestra a number of times. Nathalie also spent two months with the Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra in the 2018 season as part of its ‘Pit Perfect’ Scheme. In 2018 Nathalie performed Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante with the Magna Sinfonia.

Chamber music is another passion; as a member of the Halcyon Quartet, formed in 2012 by four students at the Royal Academy of Music, Nathalie has performed with the quartet twice at St. Peter’s Eaton Square, at the Royal Opera House and in the 2018 Bermuda Music Festival. The quartet is currently the ensemble-in-residence at Holy Sepulchre London and recently launched an online concert series.