A varied and insightful debut album from American cellist John-Henry Crawford, named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation, featuring Brahms, Shostakovich and Ligeti.

DIALOGO

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Sonata for Piano and Cello No.2 in F Major, Op.99

1. I Allegro vivace

2. II Adagio affettuoso

3. III Allegro passionate

4. IV Allegro molto

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

Sonata for Solo Cello

5. I Dialogo

6. II Capriccio

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Sonata for Cello and Piano in D Minor, Op.40

7. I Allegro non troppo

8. II Allegro

9. III Largo

10. IV Allegro

John-Henry Crawford, cello

Victor Santiago Asuncion, piano

This program explores several different modes of a concept that is vital to the fabric of our lives, our relationships, and even the progress of our society as a whole — dialogue. The opening movement of the Ligeti Sonata, titled Dialogo, is an ideal musical encapsulation of this theme and the inspiration behind the title of the album. A story of unrequited love, young Ligeti fell for a fellow student, Annuss Virány, who was a cellist. He wrote the first movement as a metaphorical love duet for her. As one voice begins in inquiry, another responds, until eventually they merge together, singing in tandem.

Throughout the whole sonata, these characters question, reply, plead, and even shout at one another. This concept is equally present in the sonatas with piano by Brahms and Shostakovich. After the grandiose introduction in Brahms’ Op.99 sonata, the two instruments pass off contrapuntal lines in a flowing “conversation.” This musical discussion morphs into more disjunct motives, and through the use of a variety of textures and rhythmic impulses throughout the later movements, Brahms sustains this conversation as a glue that holds the entire work together.

Finally, in the Shostakovich, we are exposed to a different mode of dialogue that, similar to Ligeti’s Sonata, was born out of life events. Having fallen in love with a young translator, Shostakovich and his wife divorced for a time after she became aware of the affair. This D minor sonata was written during that period of separation and reflects Shostakovich’s frame of mind – one of frustration, searching, and isolation, with the cello line as protagonist, i.e., Shostakovich. The desolate Largo suggests an inverse of this concept of dialogue. It begins in a sonic representation of a soliloquy: Shostakovich wandering and wondering to himself as he recalls motifs from the first movement.

Dialogue is something humans cannot live without, and it is my hope that this album can be a musical reminder to pursue more dialogue with one another, especially after a year as isolating as 2020.

John-Henry Crawford

While he was in Switzerland in 1886, a year after he completed his Fourth Symphony, Johannes Brahms turned his attention to smaller-scale works, including two violin sonatas, a piano trio and the Cello Sonata No.2 in F major, Op.99, which was published in 1887. It had been over 20 years since Brahms had completed his Cello Sonata No.1 in E minor, Op.38 (1862-65), although the F major work’s second movement may bridge the gap between the two, as it seems likely that it was conceived for the earlier piece. The Second Sonata was composed for the cellist who had made the First popular, Robert Hausmann, who was famed for his expansive and muscular tone and who in the following year would perform the Brahms Double Concerto with the violinist Joseph Joachim.

The premiere of the Cello Sonata No.2 was given in Vienna by Hausmann and Brahms in November 1886. The composer Hugo Wolf was in attendance, but was scathing: “What is music, today, what is harmony, what is melody, what is rhythm, what is form if this Tohuwabohu [Hebrew word meaning formless chaos] is seriously accepted as music? If, however, Herr Dr Johannes Brahms is set on mystifying his worshippers with this newest work, if he is out to have some fun with their brainless veneration, then that is something else again, and we admire in Herr Brahms the greatest charlatan of this century and of all centuries to come.”

Brahms’s approach to his Cello Sonata No.1 is illustrative of his treatment of the two instruments in the Second Sonata. He originally entitled the earlier piece a Sonate für Klavier und Violoncello, with the piano listed first, indicative of his opinion that the piano “should be a partner – often a leading, often a watchful and considerate partner – but it should under no circumstances assume a purely accompanying role”. This relationship continues in the Sonata No.2, with tempestuous exchanges between the two protagonists in the opening movement – to the extent the piano’s tremolandi risk engulfing the cello. The music also exhibits a newfound economy in Brahms’s melodic writing: the initial theme boils down to a two-note motif, C-F, its semiquaver-minim rhythm evolving via the process of developmental variation. The device is so fluid that it spills over into the secondary thematic material as well.

The singing Adagio affetuoso, in the surprising key of F-sharp major, may have been intended for the E minor Sonata, but its style is recognisably that of the composer’s late music. Brahms’s friend Elisabet von Herzogenberg, on receiving a copy, “revelled in the beautiful warm sounds of the Adagio, and especially at the magnificent moment when we find ourselves again in F-sharp major, which sounds so marvellous.” Of the third movement, she wrote: “I’d like to hear you yourself play the Scherzo, with its driving power and energy (I can hear you constantly snorting and grunting in it!) No one else would succeed in playing it as I imagine it: agitated without rushing, legato and yet inwardly restless and propulsive.” The final movement is remarkably light after the preceding gravitas; a refreshing digestif following a substantial meal.

Hungarian composer György Ligeti composed his Sonata for Solo Cello in two stages, in 1948 and 1953. He recalled in 1989: “The end of the war, and with it the Nazi dictatorship, released an unprecedented pent-up energy and vigour, which found expression in a suddenly flourishing artistic and intellectual life”. This freedom was short-lived; when Hungary became a Communist country in 1949 many artistic works were censored, including music by Bartók, Britten, Debussy, Ravel, Schoenberg and Stravinsky. Ligeti felt the absence of external precedent and kept his experimental scores private. He later wrote: “In 1951 I began to experiment with very simple structures of sonorities and rhythms as if to build up a new kind of music starting from nothing. My approach was frankly Cartesian, in that I regarded all the music I knew and loved as being, for my purpose, irrelevant and even invalid. I set myself such problems as: what can I do with a single note? with its octave? with an interval? with two intervals? What can I do with specific rhythmic interrelationships which could serve as the basic elements in a formation of rhythms and intervals? Several small pieces resulted, mostly for piano.”

Yet the Solo Sonata was not purely the result of musical experimentation; it had a more personal genesis. In 1948, towards the end of his studies, Ligeti found himself in love with a fellow student at the Budapest Music Academy, cellist Annuss Virány. Rather than telling her directly, he composed a piece called Dialogo for Virány, who remained none the wiser. In 1953 Ligeti was approached by the well-known cellist Vera Dénes, who requested a piece, so he added the virtuosic Capriccio to the Dialogo, which alternates pizzicato and legato phrases, to create a two-movement sonata.

The Sonata for Solo Cello was not embraced by the stringent Soviet Composers’ Union. It had outlined its dogma in 1933: “The main attention of the Soviet composer must be directed towards the victorious progressive principles of reality, towards all that is heroic, bright and beautiful. This distinguishes the spiritual world of Soviet Man and must be embodied in musical images full of beauty and strength”. Ligeti’s work did not match these values. He recalled: “Vera Dénes learned the Sonata and played it for the committee. We were denied permission to publish the work or to perform it in public, but we were allowed to record it for radio broadcast. She made an excellent recording for Hungarian Radio, but it was never broadcast. The committee decided that it was too ‘modern’ because of the second movement.” The work was not performed again until 1979, but soon became a staple of the cello repertoire, and was used as an audition piece in the Rostropovich Cello Competition in Paris.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Sonata in D minor was written during a painful period in the composer’s life. He was 27 and had embarked on an affair with the translator Elena Konstantinovskaya, in the meantime agreeing to a temporary separation from his wife, Nina, who left for Leningrad while Shostakovich remained in Moscow. The Sonata was begun just after her departure. Soon after he completed the work, Shostakovich asked Nina for a divorce, but they were reunited in 1935, and although the piece possesses a clean classicism in terms of form, its directness of emotion may reflect aspects of these events.

There are parallels between Shostakovich’s personal life and his musical development at this time: crisis, exploration of other options, return to the familiar. Shostakovich’s brief creative crisis included the destruction of youthful scores, and toying with modernism. The Cello Sonata, influenced by Beethoven, represents a return to ‘classical’ forms; concise and economical, it heralds the more mature style that would emerge with the Fifth Symphony.

The first movement was composed in two days, in August 1934, with the whole work completed during the following month in the Crimea, shortly before the composer’s 28th birthday. The Sonata is dedicated to cellist Viktor Kubatsky, with whom Shostakovich gave its premiere in the Small Hall of the Leningrad Conservatory, on Christmas Day 1934. Kubatsky was cellist of the Stradivarius Quartet, and an old friend; the pair toured together, performing this work alongside music by Rachmaninov and Grieg.

The structure of the Sonata follows classical conventions, including a sonata-form opening movement. The cello melody, a mixture of lyricism and urbanity, is accompanied by delicious harmonies in a piano part that doubles its melody with both hands, two or three octaves apart. That this is a piece for two equals is clear as the piano drives the opening theme to its climax before ushering in the eloquent second theme in the unexpected key area of B major. This melody is undercut by a martial ostinato, leading to the crisp rhythms of the central section. The coda, marked Largo, brings together the opening theme and marching rhythm, the string instrument’s muted tone and the piano’s octaves anticipating Shostakovich’s later Viola Sonata.

Opening with vigorous cello scales, the Scherzo is characterised by constant rhythmic momentum. For the softer secondary theme, the cello plays glissandi in harmonics with the piano in octaves, the cello’s delicacy jarring against crudely rustic textures. The Largo begins with an ascending motif in the cello that recurs and is developed later in the movement. The piano provides an ominous undercurrent with its three-note ostinato, before taking up the main theme amid restless cello writing, leading to a melancholy coda.

In the finale, Shostakovich’s searing wit is to the fore; there are overt references to Beethoven’s style, which is treated to moments of biting satire. The piano is given to outbursts of virtuosity, including a cadenza that alludes to a Beethoven Rondo also quoted in Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No.1. The cello vies for attention, at last taking over the piano’s busy semiquavers, allowing the piano to regain its dignity in time for the coda.

© Joanna Wyld, 2021

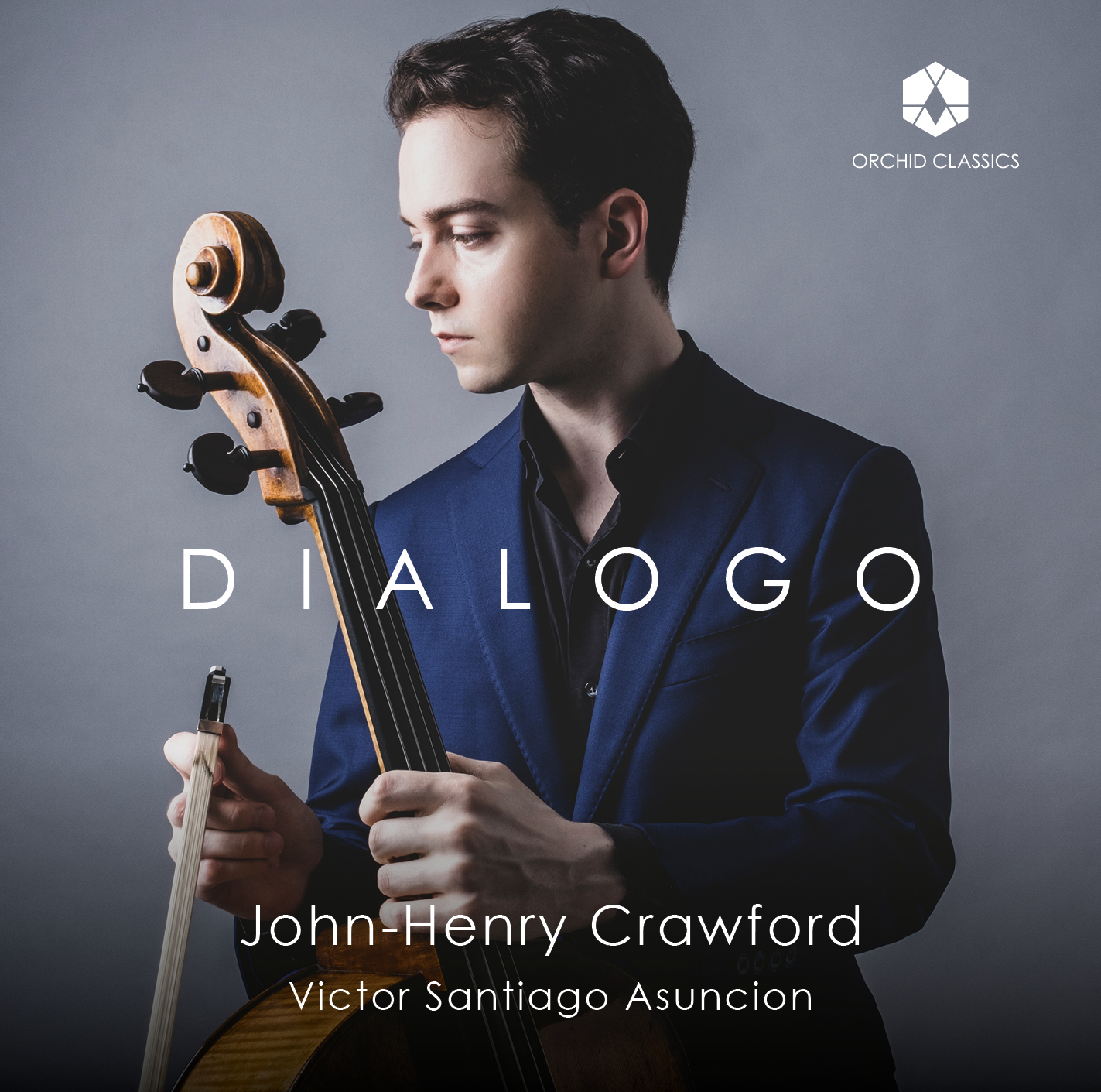

American cellist John-Henry Crawford was named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation in 2019, and his debut album demonstrates exceptional insight and nuance in a varied and fascinating programme, performed with pianist Victor Asuncion.

Playing a rare 200-year-old cello smuggled out of Austria by his grandfather, Robert Popper, John-Henry Crawford performs sonatas by Brahms and Shostakovich alongside Ligeti’s Solo Sonata. Brahms insisted that the piano was the cello’s equal in his Cello Sonatas, and the F major Sonata gives Victor Asuncion plenty of opportunities to shine. Ligeti’s Solo Sonata has had a turbulent journey from romantic gesture to Soviet censorship to staple of the repertoire, and Shostakovich’s D minor Sonata grew out of a troubled time in his life, but in both cases the cello is given an array of lyrical, passionate and technically demanding material, performed here with great flair.

John-Henry Crawford

Cello

Born in the small Louisiana city of Shreveport, cellist John-Henry Crawford has been lauded for his “polished charisma” and “singing sound” (Philadelphia Inquirer) and in 2019 was First Prize Winner of the IX International Carlos Prieto Cello Competition and named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation. At age 15, Crawford was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music and went on to complete a Master of Music at The Juilliard School and an Artist Diploma at the Manhattan School of Music. He has appeared in recital and as concerto soloist in 25 states as well as Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Mexico, and Switzerland.

Crawford commands a strong Instagram presence, attracting many thousands of viewers to his project #The1000DayJourney, where he films daily videos from his practice and performances for over 55,000 followers (@cellocrawford). His numerous competition prizes also include Grand Prize and First Prize Cellist at the 2015 American String Teachers National Solo Competition, the Dallas Symphony’s Lynn Harrell Competition, the Hudson Valley Competition, and the Kingsville International Competition. He has competed in the Tchaikovsky and Queen Elisabeth competitions and was accepted at the prestigious Verbier Academy in Switzerland.

Crawford is from a musical family and performs on a rare 200-year-old European cello smuggled out of Austria by his grandfather, Dr. Robert Popper, who evaded Kristallnacht, and a French Tourte “L’Ainé” bow from 1790.

Learn more at www.johnhenrycrawford.com

Victor Santiago Asuncion

Piano

Hailed by The Washington Post for his “poised and imaginative playing”, Filipino-American pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion has appeared in concert halls in Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, Spain, Turkey and the USA, as a recitalist and concerto soloist.

A chamber music enthusiast, he has performed with artists such as Lynn Harrell, Zuill Bailey, Antonio Meneses, Joshua Roman, Giora Schmidt, the Dover, Emerson, and Vega String Quartets. He was on the chamber music faculty of the Aspen Music Festival, and the Garth Newel Summer Music Festival. He was also the pianist for the Garth Newel Piano Quartet for three seasons. Festival appearances include the Amelia Island, Highland-Cashiers, Music in the Vineyards, and Santa Fe.

His recordings include the complete Sonatas of L. van Beethoven for Piano and Cello, Sonatas by Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff with cellist Joseph Johnson, the Rachmaninoff Sonata with the cellist Evan Drachman, and the Chopin and Grieg Sonatas, also with cellist Evan Drachman. He is featured in the award-winning recording “Songs My Father Taught Me” with Lynn Harrell, produced by Louise Frank and WFMT-Chicago. Mr. Asuncion is the Founder, and Artistic and Board Director of FilAm Music Foundation, a non-profit foundation that is dedicated to promoting Filipino classical musicians through scholarship, and performance.

Victor Santiago Asuncion is a Steinway Artist.

Click the button above to download all album assets.