Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Schubert on Tape

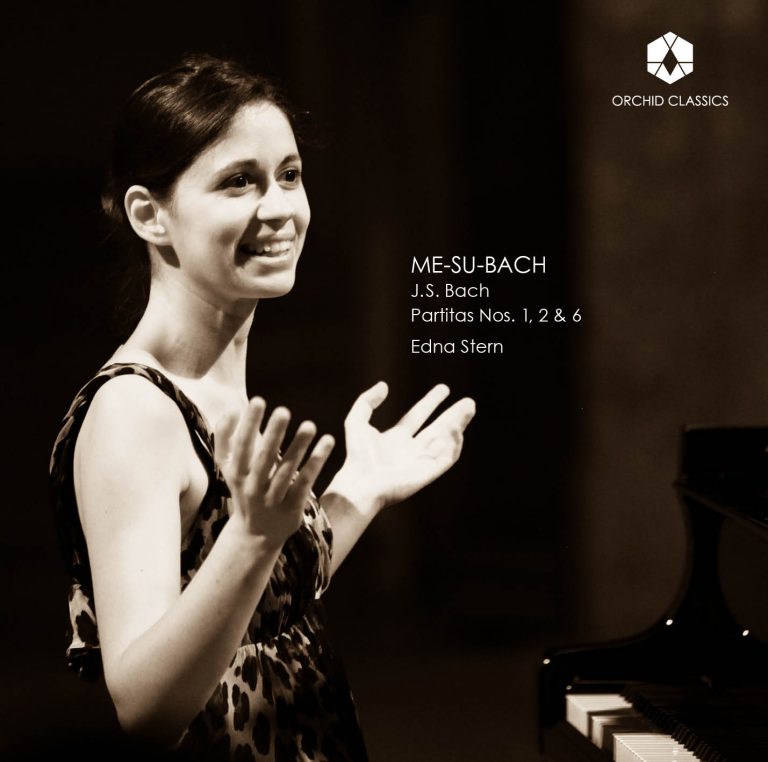

Edna Stern, piano

Release Date: Feb 4th

ORC100192

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

4 Impromptus, D.899 (Op.90)

1. No.1 in C minor – Allegro molto moderato

2. No.2 in E flat major – Allegro

3. No.3 in G flat major – Andante

4. No.4 in A flat major – Allegretto – Trio

6 Moments Musicaux, D.780 (Op.94)

5 No.1 in C major – Moderato

6. No.2 in A flat major – Andantino

7. No.3 in F minor – Allegro moderato

8. No.4 in C sharp minor – Moderato

9. No.5 in F minor – Allegro vivace

10. No.6 in A flat major – Allegretto

Edna Stern, piano

Schubert on tape

Whenever I release a new recording, I am invariably asked whether I performed this time on a modern instrument or on an original instrument.

Performing music on an original instrument generally implies that the musician is playing on an instrument (or a facsimile thereof) dating from the period of composition of a given piece of music.

This is also called “historically informed performance” or “authentic performance practice.” Webster’s Dictionary offers the following definition: “the practice of performing musical works from an earlier period, using instruments modelled on those of the period and in a style as close as possible to that of performances of the time.”

Since its origin in the middle of the 20th century this musical movement, which was first addressed to the medieval, Renaissance and Baroque repertoire, has evolved and has been applied to the classical and romantic corpus as well. This historicist orientation was at least partly inspired by a desire for greater faithfulness to the ideas and aesthetics of composers and was motivated by the search for truth and authenticity in the interpretations of their pieces.

I enjoy playing and recording on “authentic” instruments. But as a performer I don’t believe that such an instrument is required if one seeks quality, depth, and fidelity to the composer’s intent in an interpretation. In my view every instrument, whether original or modern, possesses a range of sound possibilities, which the musician must exploit sensitively to bring out what is essential to the music.

The focus in this recording is not on the instrument but rather on the recording process, which I find more crucial to the quality of the renditions than the choice of instrument. After many years of recording and producing CDs, I felt the need to go back to a mode of recording practice that would more faithfully do justice to the music and Schubert’s humane masterpieces in particular.

I first realised the negative impact of today’s recording practices while I was working on my Schumann CD back in 2006. The possibilities afforded by digital technology are so vast that a sound engineer can now just edit the sound waves and piece together fragments of different interpretations into a single, seemingly seamless interpretation.

As I listened to the first edit of my Fantasy Op.17, I was shocked to encounter an interpretation that I myself could never have played or even imagined. It was as if I were listening to a monster, some hybrid creature constructed from bits and pieces assembled by the sound engineer according to his own logic, built from what he deemed the “best” excerpts from my recording session. For me though, the resulting recording made absolutely no sense.

He was an excellent and sympathetic sound engineer, and after I explained that his vision of the Schumann Fantasy did not match my own, he gracefully offered to give me all the session’s takes so I could draw up my own editing plan. Since then, I’ve outlined editing plans for all my solo recordings, tending to use single takes for whole movements. When working with the orchestral and chamber music repertoire I’ve had to adapt to contemporary fashion, and in these endeavours, I begin with the editing plans designed by the sound engineers in charge of these recordings. These experiences have led me to conclude that today’s massive use of editing—or perhaps I should say overuse, in which every little mistake or imperfection is corrected, and “magic moments” are strung together one after another—has done more to hinder music than to serve it.

I therefore decided to let go of all digital editing. I am ever so grateful to Peter Qvortrup and AudioNote UK, who have enabled me to press the reset button and record on analogue tape, as did all my favorite pianists from the golden age such as Yves Nat, Wilhelm Kempff, Cziffra, Backhaus, and many others. Inevitably in our era we will usually listen to digital recordings, given its comparable ease, but there is—undeniably—an ineffable quality to the analog sound. This recording will also be released on vinyl, in all analogue. I’d also like to express my special thanks to Darrel Sheinman and Gearbox Records for all their help in making this recording, as well as my sincerest thanks to Matthew Trusler of Orchid Classics for his constant support.

What is the problem with fixing with editing all the mistakes, and why do I prefer whole takes? Imagine a human’s gait vs a robot’s, or even a human dance vs a robot’s dance. There is a sense of freedom – even of danger – with the human and all their flaws. There is a coherent continuation of movement. Moreover, there is a sense of life. Yes, a singer’s voice can be made to continue indefinitely, but there is life and music in the singer’s attempt to stretch her voice. (In fact, tight-rope artists would usually add a fake stumble as without the sense of danger some of the interest is lost.)

In various areas of life, there is a growing call to press the reset button and to limit the negative use and impact of digital modifications. I would compare the use of corrective digital editing in music, aimed at altering how a prior interpretation sounded, to the use of Photoshop and other such means to edit pictures, more specifically those that help shape a person’s image for others.

It is tempting to do this, I won’t deny it. A part of me would rather be seen without any wrinkles, younger, svelte, graced with thick long shining hair, an elegant nose and—why not?—blue eyes. I would perhaps derive some pleasure from looking at such an image of myself. But then I’d be faced with the question: Is this really me?

In painting, it would amount to artistic sacrilege to “correct” the lines and colours of a work’s figures and forms, even if imperfect: the unevenness is fully part of what makes the painter distinct. Imagine correcting a painting by Cézanne whose subject, let’s say fruit arranged on a table, has been altered in this way. It wouldn’t be a Cézanne anymore.

In music, correcting each little mistake, or adding reverb for a more agreeable sound that erases the little imperfections, creates an entirely new iteration of the piece. For me, this approach strips the interpretation of its depth and original character, but above all the use of digital editing to correct wrong notes is an act that gives greater importance to the notes than to the idea or interpretation of the music. This bias has come to shape the priorities of recent decades, resulting in interpretations and recordings that resemble one another so as to conform to the ideal of flawlessness the classical music industry has created. Its effect on the life of classical music has been devastating.

This recording was made directly to tape, without any editing. During my preparations my primary task was to re-educate myself, to free myself from any pedantic preconceptions related to this era. To come back to the gait metaphor, classical musicians are expected today to play with almost a robotic regularity. We are used to expect this from ourselves, certainly when playing for a competition or during a recording session, but even during concert-live performances. It’s always in the back of our head; we are constantly aware of the amount of freedom and risk we may take. We limit ourselves to only x possibilities because past those, mistakes and other irregularities may appear. I decided that as long as the ideas of my interpretations were expressed, any mistakes or other flaws would be of little importance. Fixing the imperfections removes life and music from the piece and my priority here was to be human, not a robot.

I purposefully chose takes that I found more interesting from the interpretation perspective and didn’t necessarily choose the more perfect and mistake-free ones. While Schubert may not be the Everest in terms of technical difficulty, he is certainly up there with regards interpretation, in being one of the most difficult composers to reach the depth of interpretation needed to express the beauty and mystery that is inherent to his work. As I listened to my playing of Schubert with its many flaws, I couldn’t help but sigh and think that it sounds human, all too human.

This was however my decision as I believe that interpretation, not the notes, is the path that leads to discovery of the music, and there may well be pebbles, even big stones in this case, along the path.

On Schubert

It is on a path that I have always imagined Schubert, the Wanderer, roaming the fields, a walking stick in hand and a light backpack on his shoulders containing the precious music paper he’d take out while resting under a tree, writing his melodies inspired by nature.

The force of nature is what strikes me most powerfully in Schubert, how nothing can stop the flow of his music, of the river, the lava pouring out of the volcano. He came from a modest family: his father was a schoolmaster, and he was torn between his teaching duties, the need to earn a living, and the wish to compose in freedom. Encouraged by his friend Franz von Schober, a wealthy law student, he finally abandoned teaching and devoted himself wholly to composition. Schubert’s reputation grew, but editors were reticent to publish his pieces. The two cycles presented in this recording, the Moments Musicaux D.780, and the Impromptus D.899, were apparently composed during 1827, with Schubert already gravely ill from the syphilis that would kill him in November 1828. It is said that he had arranged to be given counterpoint lessons from Simon Sechter on November 4, mere weeks before his death. In 1969 a batch of these exercises he then composed, addressed to Secther, were discovered in Vienna.

It is humbling to know that a genius like Schubert, who by then had already written the Impromptus, the Moments Musicaux and his last piano sonatas, (not to mention countless songs, symphonies, and quartets!) still felt the need to improve in a particular area—in counterpoint, and to make exercises.

These pieces reflect the turn music is about to take, the Classical era yielding to the Romantic. They reflect the rise of the middle class and of salon evenings that no longer belonged exclusively to the aristocracy, and that favoured miniature pieces over the longer piano sonata form.

These short pieces are based on mono-thematic material, inspired by the mono-thematic lied, which also announces the onset of Romanticism and revived interest in the forms and repertoire of the Baroque. Hence, Schubert’s interest and investment in counterpoint exercises.

The Baroque forms were illustrious in their development of mono-thematic material, in the way they showed such material’s evolution through modulations. For example, see the piece’s Theme, which acquires different colours in different tonalities, and its constantly changing nature through its interaction with the other voices.

Another significant aspect regarding the use of mono-thematic material lies in the minimalist connection between the different sections. The lied A B A structure that is mostly used here is a form in which a Theme (A) is presented, followed by a middle section (B), and finally, closing the piece, the return of the Theme. The connection between A and B is deeper than what it would seem to be on the surface. The middle sections are often a derivation or a variation on a part of the original A, and inside his B sections Schubert continually probes how far he can bend the original material and transform it.

Unlike most of this recording’s pieces, which are based on the lied form, the Impromptu No. 1 conveys the evolution of its Theme in one long variation movement. The Theme, sometimes played in a single voice and sometimes in harmonic chords, is subject to continual change throughout the piece, manifesting itself sometimes in Major mode, graced with light, happy triplets, and sometimes in Minor mode, accompanied by obsessive and ominous repeating notes. The Theme is always in flux, reminding us of Heraclitus’s famous dictum:

“You cannot step into the same river twice, for other waters are continually flowing on.”

© Edna Stern

Edna Stern

Piano

Edna Stern began her studies in Israel with Viktor Derevianko, a student of Heinrich Neuhaus. She continued studying with Krystian Zimerman at the Basel Hochschule and with Leon Fleisher at the Peabody Institute and at the Lake Como International Piano Foundation. Her repertoire ranges from Bach to Berio. Her recordings are highly praised by critics, receiving such awards as Diapason d’Or, Diapason Découverte, Arte Best CD, Gramophone upcoming artist, and Sélection Le Monde. Her last recording, released by Orchid Classics and dedicated to Hélène de Montgeroult received a Critic’s Choice of the Year 2017 of the Gramophone Magazine and Choice of France Musique, the French radio.

Edna Stern has performed at prestigious halls and festivals such as the Philharmonie of Paris, Concertgebouw of Amsterdam, Munich’s Hekulessaal, Paris’ Châtelet Theater, Moscow’s Music-House, Petronas in Kuala Lumpur and Musashino hall in Tokyo; performing in solo recitals and with orchestras, with conductors such as Claus Peter Flor and Andris Nelsons. Stern gives masterclasses all over the world, in such places as the CNSM of Paris, Rutgers University, and Tel-Aviv Zubin Mehta School of Music.

She has been a professor at the Royal College of London since 2009 and her musical activities include working with great artists in other art fields, like film director Amos Gitaï, as well as Etoile/Leading principal dancer from the Paris National Opera Ballet, Agnès Letestu.