Artist Led, Creatively Driven

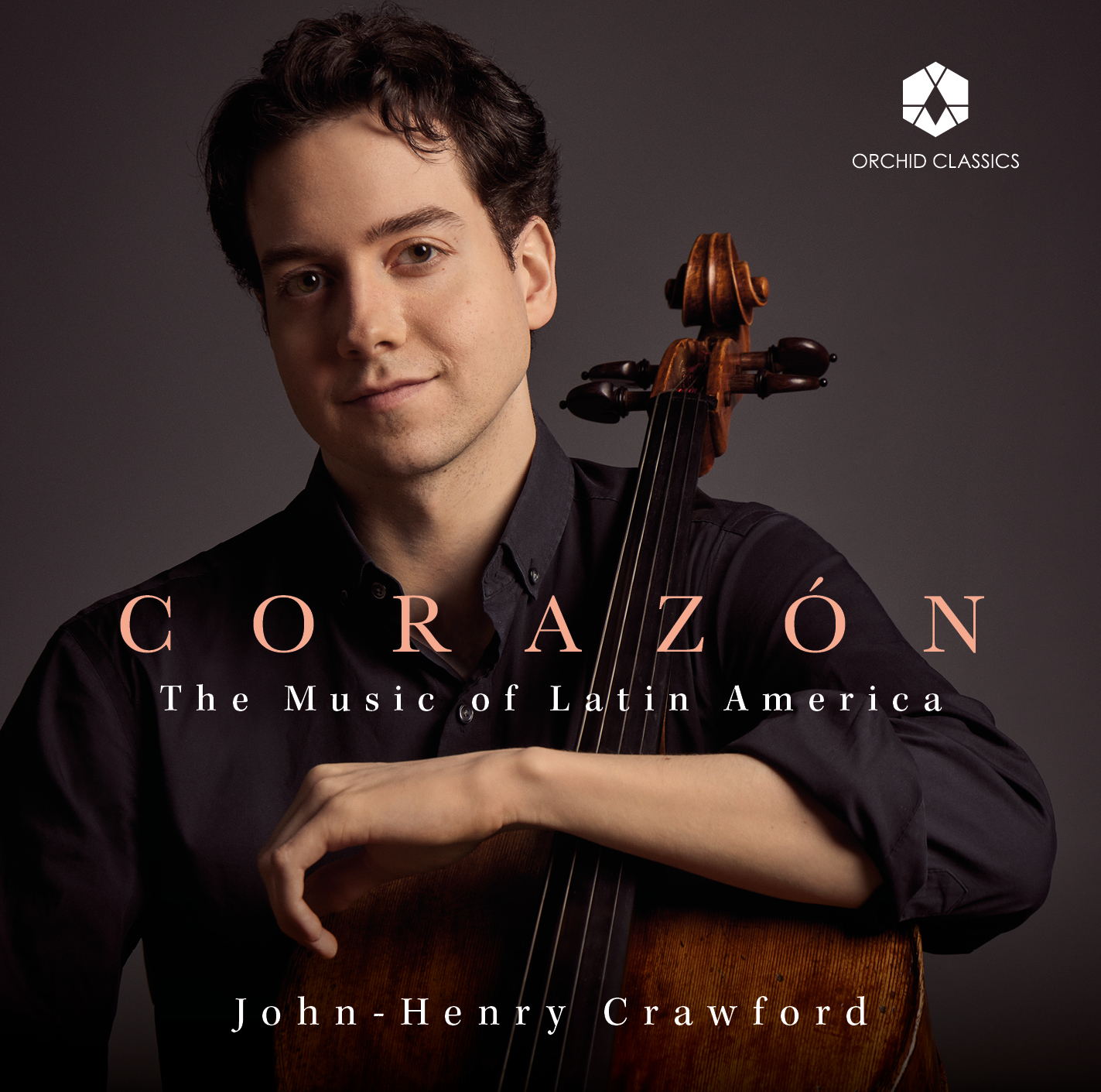

CORAZÓN

John-Henry Crawford, cello

Victor Santiago Asuncion, piano

JIJI, guitar

Release Date: 17th June

ORC100198

CORAZÓN

Leo Brouwer (b.1939)

1. Canción de cuna*

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959)

2. O canto do cisne negro, W122

Carlos Guastavino (1912-2000)

3. Pampamapa

Manuel Ponce (1882-1948)

4. Por ti mi corazón

Egberto Gismonti (b.1947)

5. Água e Vinho*

Manuel Ponce

6. Estrellita*

Arranged by JIJI / Jascha Heifetz

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992)

7. Le Grand Tango

Heitor Villa-Lobos

8. Pequeña Suite: Melodia

9. Ondulando

Manuel Ponce

Sonata in G minor for violoncello and piano

10. Allegro selvaggio

11. Allegro

12. Arietta

13. Allegro burlesco

Astor Piazzolla

14. Oblivion

John-Henry Crawford, cello

Victor Santiago Asuncion, piano

JIJI, guitar*

According to the Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia, Mexican musician Manuel Ponce (1882-1948) was the most significant composer in the modern revival of guitar music. Ponce’s body of guitar music is almost unparalleled in the 20th century, rivalled only by that of Heitor Villa-Lobos and Leo Brouwer. He was Mexico’s first nationalist composer, but he also drew upon Spanish and Cuban styles, as well as European and American impressionism; his music ranges from romanticism to bitonality and atonality. Villa-Lobos met Ponce in Paris in the 1920s and later recalled: “I remember that I asked him at that time if the composers of his country were as yet taking an interest in native music, as I had been doing since 1912, and he answered that he himself had been working in that direction. It gave me great joy to learn that in that distant part of my continent there was another artist who was arming himself with the resources of the folklore of his people in the struggle for the future musical independence of his country.”

With its irresistibly charming melody, Ponce’s most famous work is his song Estrellita (‘Little star’, 1912) – the first of two Canciones Mexicanas – heard here in an arrangement for cello and guitar. In a similar vein, Por ti mi corazón (‘For you my heart’, 1925) is the second of Ponce’s Canciones populares mexicanas.

The Sonata for cello and piano in G minor (1922), dedicated to Uruguayan cellist Oscar Nicastro, is a fine example of Ponce’s Latin American modernism. The work opens with a stormy, surging Allegro selvaggio, the ‘wild’ momentum of the opening theme softening into romantic lyricism with a long-breathed cello melody. Contrasts between these two characters continue throughout the movement, explored via compelling dialogue between the cello and piano. The second movement bears the unusual marking Allegro alla maniera d’uno studio (‘Lively, in the manner of a study’), and opens with jangling piano and pizzicato cello, gaining in energy as the cello, now arco, articulates a vigorous theme. The movement reaches what feels like an ending before Ponce introduces a much slower section, the cello in its lower register and in contemplative mood, before the opening material is reprised. An Arietta follows, explicitly linking the cello with the human voice, its sonorous utterances coloured by the piano’s wealth of shimmering textures. Two arresting piano chords usher in the ‘burlesque’ finale, which marches forwards in a manner more purposeful than playful, but the slower, ardent cello writing that has cropped up throughout the sonata is recalled once more before the almost abrupt surprise of the final bars.

Leo Brouwer (b.1939) has been at the forefront of Cuban musical life for decades. Following his early guitar studies, he started composing, self-taught, before attending The Juilliard School. Brouwer helped to launch the avant-garde scene in Cuba in the 1960s and has conducted numerous orchestras there and internationally. His output may be divided into three main phases: essentially nationalistic (c. 1955-62), avant-garde (1962-67), and then a mellowing of that modernism, especially after the 1980s, when what he described as a “new simplicity” emerged. He said of his musical inspiration: “I use any form to help me find musical forms: that of a leaf, of a tree or geometric symbolisms. All these are also musical forms; despite the fact that my works appear very structured, what interests me is sound”. Heard here in an arrangement for cello and guitar, Brouwer’s Canción de cuna (Berceuse) from Dos temas populares Cubanos (1978) is sometimes known as the Afro-Cuban Lullaby and is based on the Drume negrita by Cuban composer and pianist Eliseo Grenet (1893-1950).

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) was the 20th century’s most significant Brazilian composer of art music, combining European models with Brazilian styles. Villa-Lobos received his earliest musical education from his father, Raúl Villa-Lobos, who taught his son to play the cello – which became the composer’s favourite instrument. Villa-Lobos became fascinated by the popular music of Rio de Janeiro, teaching himself the guitar in order to participate in the city’s musical life. After dropping out of medical school, the teenage Villa-Lobos earned money playing the cello in hotels, the Teatro Recreio and the Odeon cinema.

The Pequeña Suite (‘Little Suite’) of 1913 is Villa-Lobos’s earliest published work for cello and piano and reflects his love of J.S. Bach, which developed at an early age thanks to his aunt. The suite was premiered in the summer of 1919 at the Salão Nobre in Rio de Janeiro, with Villa-Lobos playing the cello and Roberto Soriano at the piano. The composer’s flair for writing beautiful melodies is demonstrated in the ‘Melodia’, the fifth of six movements.

O canto do cisne negro or Chant du cygnet noir (‘Song of the black swan’, 1917) was adapted by Villa-Lobos from his 1916 symphonic poem Naufrágio de Kleônicos (‘The Shipwreck of Kleônikos’). The piece opens with a rippling piano texture, over which the cello plays a seamless melody punctuated by exotic inflections. ‘Rippling’ or Ondulando (1914) was originally written for solo piano; John-Henry Crawford’s arrangement brings out the work’s captivating melodic line.

Carlos Guastavino (1912-2000) was an Argentine composer and pianist who reached musical maturity during the 1940s, when Latin American national feeling was high (events such as the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20 were still fresh in the memory, and in Argentina this was the era of Juan and Eva Perón). Guastavino’s output almost always possessed a national flavour, reflecting his love of Argentina and its wildlife especially and embracing folk cultures such as the Gauchesco (South American cowboys) and Criollo (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies). He favoured tonal music and traditional forms, raising objections to aspects of modern music. From the 12 Canciones populares (1968) we hear No.6, ‘Pampamapa’ (‘Map of the plains’), originally a song to words by Hamlet Lima Quintana that are at once poignant and defiant: “On the trail, my land, so sleepless. / I will give you my dreams, give me your calmness.”

Egberto Gismonti (b.1947) is a Brazilian composer who studied at the Nova Friburgo Conservatory and with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Influences have included music reflecting his own Arabic and Italian heritage, choro and bossa nova, Brazilian Indian themes, jazz, and the music of Villa-Lobos and Stravinsky; like Villa-Lobos, Gismonti taught himself to play the guitar. Arranged for cello and guitar by John-Henry Crawford, Água e Vinho (1972) is a hypnotically beautiful song from Gismonti’s album of the same name, originally to lyrics by Geraldo E. Carneiro.

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) was born in Buenos Aires before moving with his family to New York in 1924, escaping Argentina’s economic crisis to the cultural melting pot of Greenwich Village, where Astor’s father, Vincent, ran a barber’s shop. Vincent gave Astor a present for his eighth birthday: a bandonéon that he’d found in a pawn shop. “He brought it wrapped in a box, and I was happy, believing that it was the skates that I had asked for many times. That was deceptive, however. In place of the skates I encountered an apparatus that I had never seen in my life. Papa sat himself on a chair, placed the thing between my arms, and said to me: ‘Astor, this is the instrument of the tango, I want you to learn to play it.’ My first reaction was to complain. The tango was the music that he listened to almost every night when he returned from work, and which I did not like.”

At first more interested in listening to Bach and jazz than playing the instrument, Astor started practising to please his father, but soon became proficient. Piazzolla moved back to Buenos Aires in 1937, studying with Ginastera. In 1954, a symphony he’d written for the Buenos Aires Philharmonic won him a scholarship to study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, who recognised where his real passions lay; she urged him to focus on the tango rather than on purely classical forms, observing: “Here you have the real Piazzolla; Astor, be true to him”. This period of study lasted for about 18 months but had such a profound impact that Piazzolla said the growth he’d experienced felt more like “eighteen years”. Back in Buenos Aires, he developed the ‘nuevo tango’ style, blending chromaticism, jazz, fugal textures, and dissonance. Not everyone was convinced: in the 1950s, when Piazzolla was conducting, a member of the orchestra sniffed, “I assume you are nothing to do with this Piazzolla who plays tangos.” Piazzolla later argued: “Those classical musicians are like that – they are from Buenos Aires, Argentineans, and yet it seems that the tango shames them. That is an old division that exists between the classical and the popular. The musicians of the Colón [the Buenos Aires opera house] look at those of the tango as if they were trash. And it should not be so. It is a big lie.”

Le Grand Tango dates from 1982, by which time Piazzolla’s music was internationally acclaimed. In a single movement for cello and piano and dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich, this passionate piece embodies the ‘nuevo tango’ style, combining tango rhythms with jazz syncopation. Dating from the same year, Oblivion is one of Piazzolla’s most famous works, its mournful melody lending itself perfectly to the plangent tone of the cello.

© Joanna Wyld, 2022

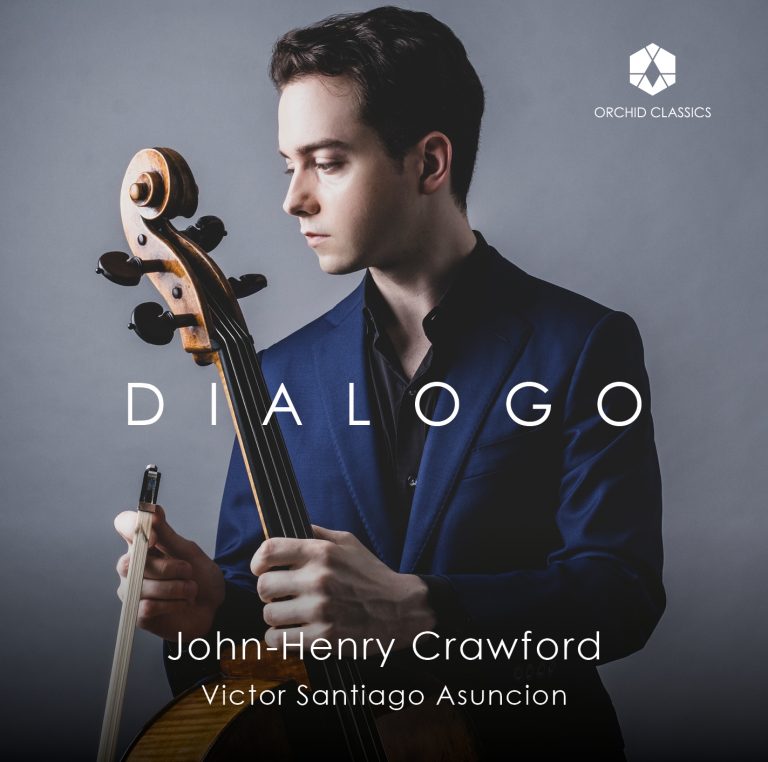

John-Henry Crawford

Cello

Born in Louisiana, cellist John-Henry Crawford has been lauded for his “polished charisma” and “singing sound” (Philadelphia Inquirer). In 2019, he won First Prize in the IX International Carlos Prieto Cello Competition and was named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation, and in 2021, he was named the National Federation of Music Clubs’ Young Artist in Strings.

At age 15, Crawford was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music and went on to complete an Artist Diploma at the Manhattan School of Music and a Master of Music at The Juilliard School. He has appeared in recital and as concerto soloist in 25 states as well as throughout Europe and South America. In its first week, Crawford’s debut album Dialogo (Orchid Classics – June 2021) appeared on the Billboard Top 10 chart as well as the top 5 on iTunes and #1 on Amazon’s Classical New Releases.

Crawford commands a strong Instagram presence, attracting many thousands of viewers to his project #The1000DayJourney, where he films daily videos from his practice and performances for over 55,000 followers (@cellocrawford).

His numerous prizes also include Grand Prize and First Prize Cellist at the 2015 American String Teachers National Solo Competition, the Dallas Symphony’s Lynn Harrell Competition, the Hudson Valley Competition, and the Kingsville International Competition. He has competed in the Tchaikovsky and Queen Elisabeth competitions and was accepted at the prestigious Verbier Academy in Switzerland.

Crawford is from a musical family and performs on a rare 200-year-old European cello smuggled out of Austria by his grandfather, Dr. Robert Popper, who evaded Kristallnacht, and a French Tourte “L’Ainé” bow from 1790.

Learn more at www.johnhenrycrawford.com

Victor Santiago Asuncion

Piano

Hailed by The Washington Post for his “poised and imaginative playing”, Filipino-American pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion has appeared in concert halls in Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, Spain, Turkey and the USA, as a recitalist and concerto soloist.

A chamber music enthusiast, he has performed with artists such as Lynn Harrell, Zuill Bailey, Antonio Meneses, Joshua Roman, Giora Schmidt, the Dover, Emerson, and Vega String Quartets. He was on the chamber music faculty of the Aspen Music Festival, and the Garth Newel Summer Music Festival. He was also the pianist for the Garth Newel Piano Quartet for three seasons. Festival appearances include the Amelia Island, Highland-Cashiers, Music in the Vineyards, and Santa Fe.

His recordings include the complete Sonatas of L. van Beethoven for Piano and Cello, Sonatas by Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff with cellist Joseph Johnson, the Rachmaninoff Sonata with the cellist Evan Drachman, and the Chopin and Grieg Sonatas, also with cellist Evan Drachman. He is featured in the award-winning recording “Songs My Father Taught Me” with Lynn Harrell, produced by Louise Frank and WFMT-Chicago. Mr. Asuncion is the Founder, and Artistic and Board Director of FilAm Music Foundation, a non-profit foundation that is dedicated to promoting Filipino classical musicians through scholarship, and performance.

Victor Santiago Asuncion is a Steinway Artist.

JIJI

Guitar

Applauded by The Calgary Herald as “…talented, sensitive…brilliant,” JIJI is an adventurous artist known for her virtuosic performances that feature a diverse selection of music, ranging from traditional and contemporary classical to free improvisation, played on both acoustic and electric guitar. Through her impeccable musicianship, compelling stage presence, and constant premieres of new musical works, JIJI’s intriguing programming solidifies her reputation as a 21st century guitarist. The Washington Post selected JIJI as “one of the 21 composers/performers who sound like tomorrow.”

Recent highlights encompass a wide array of venues, including Lincoln Center, David Geffen Hall, Zankel Hall/Stern Auditorium at Carnegie Hall, 92nd Street Y, Moss Arts Center, Green Music Center, National Art Gallery, National Sawdust, Miller Theater, Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, and Purdue Convocations.

JIJI is currently an assistant guitar professor at Arizona State University.