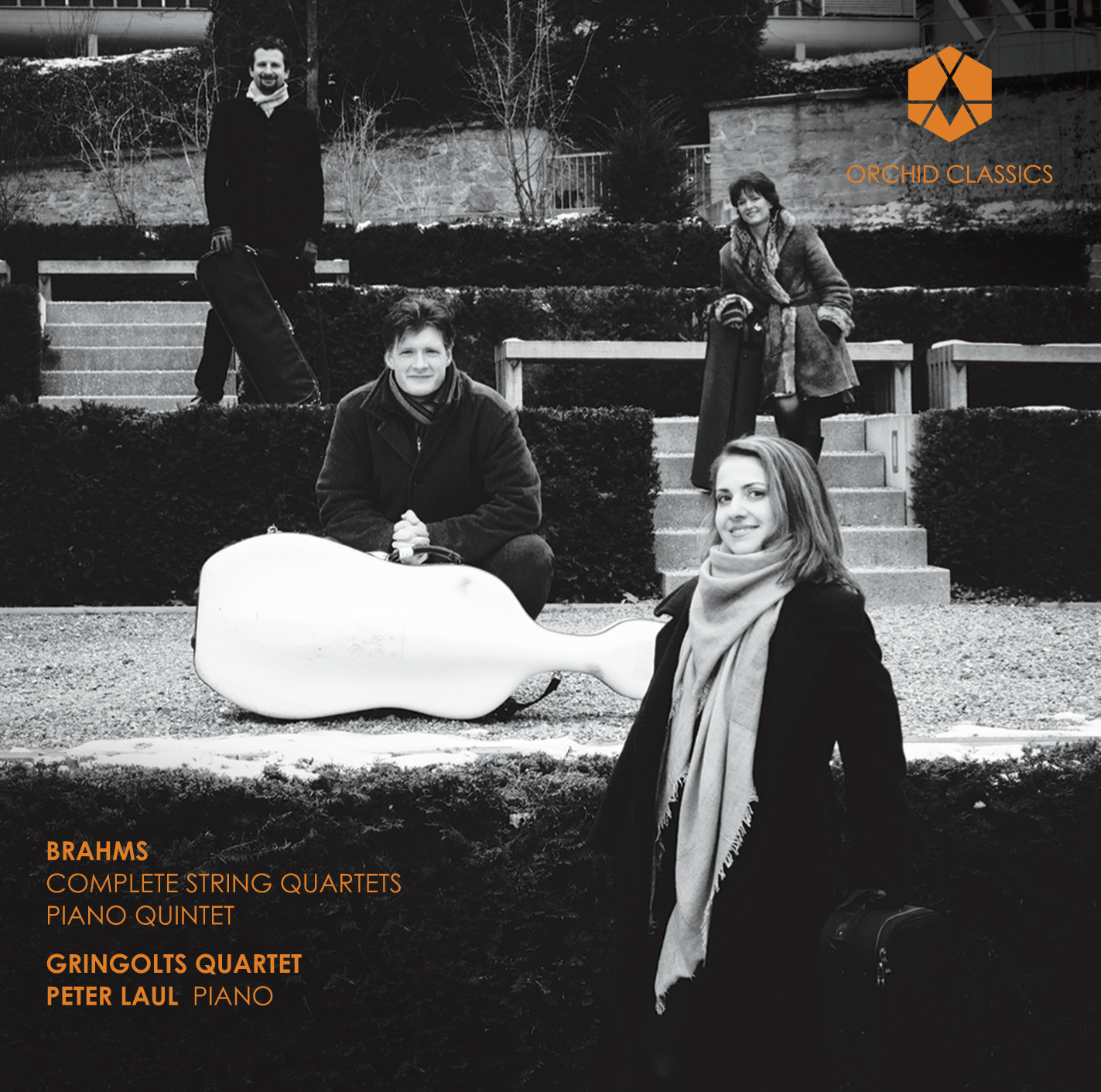

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Brahms Complete String Quartets

Gringolts Quartet

Peter Laul, piano

Release Date: June 2014

ORC100042

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

DISC 1

Piano Quintet in F minor, Op.34 (1865)

1 I Allegro non troppo 15:02

2 II Andante, un poco adagio 7:53

3 III Scherzo: Allegro 7:23

4 IV Finale: Poco sostenuto – Allegro non troppo – Presto, non troppo 10:33

String Quartet in C minor, Op.51 No.1 (1873)

5 I Allegro 9:40

6 II Romanze. Poco adagio 6:11

7 III Allegretto molto moderato e comodo 9:12

8 IV Allegro 5:53

Total time 72:05

DISC 2

String Quartet in A minor, Op.51 No.2 (1873)

1 I Allegro non troppo 13:01

2 II Andante moderato 8:53

3 III Quasi Minuetto, moderato 5:08

4 IV Finale. Allegro non assai 6:37

String Quartet in B flat major, Op.67 (1875)

5 I Vivace 9:36

6 II Andante 7:00

7 III Agitato (Allegretto non troppo) – Trio – Coda 7:28

8 IV Poco Allegretto con Variazioni 10:10

Total time 68:06

Gringolts Quartet

Peter Laul (piano)

The Piano Quintet in F minor, Op.34, which was published in 1865, forms the conclusion of Johannes Brahms’s early works and the high point of the period that the English musician Donald Francis Tovey referred to as the “first maturity”. Between 1853 (Op.8) and 1865 (Op.40) Brahms composed chamber music for such varied combinations as piano trio, string sextet, piano quartet, piano quintet, and horn trio, but not yet in the tradition-steeped genre of the string quartet. As far as the forms of the individual movements are concerned, he oriented himself more on the instrumental works of Franz Schubert than on Beethoven’s formal principles. However, in terms of tonal conception, he long remained a seeker in chamber music as he did in orchestral music, which during these years he approached only timidly in the two serenades and the First Piano Concerto. The treatment of string instruments was for him, as a pianist, virgin territory. Therefore, he tested their effect in pure string settings as well as in combinations with piano, but the decision between the different types of instruments still remained uncertain for a long time. Thus, in 1861 he composed a String Quartet in F minor that he reworked for two pianos before Clara Schumann persuaded him in 1864 to transform the composition – as a synthesis of the two earlier versions, so to speak – into the Piano Quintet, Op.34. The combination of piano and string quartet at times made possible a symphonic structure in terms of sound and form. In the first movement, this results in a balance between the series of tonalities in which the three thematic areas are heard and their respective fundamental tones, which together form the central pitches of the main theme. Unlike in earlier sonata movements, Brahms develops here a rich web of derivations, reshapings, and mutual references out of minimal intervallic elements. In the slow movement, these constructional principles continue to have an effect, but are obscured by the contrast between an emphatically plain frame and an expressive middle section. The Scherzo takes up the symphonic style of the first movement and at the same time prepares for the restrained beginning of the final movement. Typical of Brahms’s works of the “first maturity” are the pastoral or folk-like moods, as heard here in the finale, which towards the end refers back in turn to the beginning of the opening movement. Although the final movement is based on a rondo structure, Brahms avoided a superficial “happy end”, but rather maintained a contemplativeserious mood throughout. The Piano Quintet was premiered on 22 June 1866 in Leipzig and pleased the composer so much that he destroyed the manuscripts of the earlier versions. Indeed, with the Piano Quintet he created a work that has to be considered a high point of his first creative period. Since Brahms’s compositional development took place logically and, in terms of its essential characteristics, independent of external influences, the respective new compositional achievements will also be discussed within the context of the string quartets.

Brahms is supposed to have already occupied himself with string quartets before the Piano Trio, Op.8, but exaggerated self-criticism hindered him from presenting them to the public. The standard set by Beethoven’s middle and late quartets was too high. All the same, Brahms allegedly composed “more than twenty quartets” before going public with the two String Quartets, Op.51. Joseph Joachim and his quartet were involved in the preparation of the final versions, but Brahms did not dedicate the quartets to the “violinist of the century” and his ensemble, but rather to the surgeon Theodor Billroth, with whom he had previously become friends in Zurich. The String Quartet in C minor, Op.51 No.1 is a model of thematic unity across all four movements. Significant moments of the first movement’s main theme initially continue to exert an effect in the second, but then also in the fourth movement, and from there are further developed in the preceding Allegretto. All the subsequent motifs are developed either by means of recastings, sequencing, and rhythmical shiftings of these ideas, or they are accompanied by figurations that are related among themselves. The material of the exposition is not only repeated in the reprise of the finale – as in the Piano Quintet – but also condensed and intensified in its fervour. The rather sombre atmosphere of the C minor Quartet is transformed into a more amiable mood in the sibling work in A minor, the String Quartet, Op.51 No.2. Below the more relaxed surface, the many-layered relationships of the themes and their variational developmental traits are however just as stringent. On the other hand, the different characters of the movements and their inner contrasts are worked out more keenly. Thus, in the Andante, song-like moments are juxtaposed with a middle section that quotes from the second of the Hungarian Dances. The Scherzo, with its rhythmic shifts, forms an entirely contrary, shadowy intermezzo at whose centre stands a double canon on the minuet motif.

Theodor Billroth described the two quartets as “tremendously difficult technically” and “otherwise also not of lightweight content.” The finale with its echoes of a czárdás possibly alludes to Joseph Joachim’s West-Hungarian roots. The first four notes in the first violin part at the beginning of the quartet – (a)–f–a–e –might also refer to his motto “frei, aber einsam” (free, but lonely). It was therefore logical that the Joachim Quartet performed this work for the first time in public on 18 October 1873 in Berlin’s Singakademie.

In August 1876 Brahms likewise dedicated the String Quartet, Op.67 to a doctor, the Utrecht physiologist Theodor Wilhelm Engelmann. In comparison to the two Op.51 quartets with their difficult geneses – Brahms referred to them also as “forceps deliveries” – it has a nearly serene mood, and also allows itself to incorporate the styles of earlier composers: the beginning calls to mind Mozart’s “Hunt” Quartet (K458), and the slow movement Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. More pronounced than in the earlier quartets, the dancing character, too, asserts itself: the second subject of the first movement is a polka, and the theme of the variations in the finale a gavotte. The harmony seems considerably more traditional here, sometimes nearly Baroque. The preference for the lower registers stands out clearly and, especially in the third movement (Agitato), the viola is given a particularly prominent role. The fact that the whole quartet, like the First Symphony, Op.68, which was completed a year later, is conceived with an eye toward the finale becomes obvious at the latest when the “hunt” theme from the first movement is heard again in the seventh variation. Up until this last work before the long-desired breakthrough to the symphony, Brahms had brought to full maturity the process that Arnold Schoenberg was later to call “developed variation”: more important than the adherence to borders within a precast form is a synthesis of the distance from a basic idea and the rapprochement to it by means of variation processes at all levels of the composition. The String Quartet, Op.67 shows how very much the principle of the unity of thematic structure and polyphonic texture has an effect both on the fashioning of the individual movements as well as of the whole, multimovement work.

Gringolts Quartet

Ilya Gringolts (violin)

Anahit Kurtikyan (violin)

Silvia Simionescu (viola)

Claudius Herrmann (cello)

The Zurich-based Gringolts Quartet was founded in 2008, born from mutual friendships and chamber music partnerships. Coming originally from different corners of Europe and thus bringing together different musical experiences and backgrounds, the four members share a unique passion for playing music together and for the high demands presented by the string quartet repertoire.

Highlights from the past season include performances at the Lucerne Festival, the Philharmony in St Petersburg, the Oleg Kagan Musikfest in Kreuth and the Kasseler Musiktage. During the upcoming seasons they will perform a.o. at the Menuhin Gstaad Festival, the Auditori Barcelona, the Sociedad Filarmónica de Bilbao, Salzburgerfestspiele and the Società di concerti in Milano. They have already had the opportunity to collaborate with renowned artists such as Leon Fleischer, Jörg Widmann, David Geringas, Alexander Lonquich and Eduard Brunner.

Gringolts Quartet’s debut recording for Onyx was published in 2011, containing the complete string quartets and the piano quintet of Robert Schumann. This recording met with great critical acclaim, by Diapason, The Independent, Kulturspiegel and Swiss Radio DRS, amongst many others.

Together with David Geringas the Gringolts Quartet participated in the world premiere recording of Walter Braunfels’ Quintet with two cellos which got a Supersonic Award as well as an ECHO Klassik award.

The members of Gringolts Quartet all play on rare Italian instruments. Ilya Gringolts plays a Stradivarius violin, Cremona 1718. Anahit Kurtikyan plays a Camillo Camilli violin, Mantua 1733. Silvia Simionescu plays a Jacobus Januarius viola, Cremona 1660. Claudius Herrmann plays a Maggini cello, Brescia 1600. Beethoven’s last quartets were been first performed on this wonderful instrument, formerly owned by Prince Galitsin, a close friend of the composer.

Peter Laul (piano)

Peter Laul was born into a musical family in St. Petersburg, Russia and received his education at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he studied with Prof. Alexander Sandler, and where he has since become a faculty member. He won the 3rd prize and special prize for the best Bach performance in the Bremen International Piano Competition in 1995 and again, in 1997, he won the 1st prize and special prize, this time for the best Schubert sonata performance. In addition to that, in 2000 he won 1st prize at the Scriabin International Piano Competition in Moscow and, in 2003, he was awarded the honorary medal “For achievements in the Arts” by the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation.

Peter Laul has performed as a soloist with numerous Russian orchestras including the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic, the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra, the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and the Moscow State Kapella Orchestra, under the direction of conductors such as Maxim Shostakovich, Valery Gergiev, Vassily Sinaiski, Eri Klas, Jean-Claude Casadesus, Nikolai Znaider and Nikolai Alekseev among others. He has also performed with the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, Südwestdeutsche Rundfunk, the Dessau, the Bremerhaven and the Oldenburg Theatre Orchestras (Germany), the Brasilian National Symphony Orchestra, Südwestdeutsche Rundfunk, the Estonian National Symphony and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestras (Estonia) and the ‘Les Siècles’ (France) under François-Xavier Roth.

Peter Laul’s recital performances have taken him to the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Halls, the Concert Hall of the Mariinsky Theatre, the Moscow Conservatory Halls, the Moscow Tchaikovsky Hall and the new Moscow International House of Music. Elsewhere he has performed in many venues worldwide including in Paris, New York, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Bremen, Milan, Tokyo, Luxembourg and Brussels. His most recent performances have been at the Serres d’Auteuil festival in Paris, the “Les Musicales” Festivals in Colmar, “Arts Square”, “The Stars of White Nights” and “The Faces of International Pianism” in St.Petersburg, “Art November” in Moscow, the Kamchatka Spring Festival, the Saint-Riquier Festival, the Lancut Spring Festival in Poland, and the “Le Printemps des Arts” in Monaco.

Mr. Laul is a consummate chamber musician. His chamber music partners include Dmitry Kouzov, Marc Coppey, Ilya Gringolts, Graf Mourja, Sergey Levitin, Alena Baeva, Valery Sokolov, Alexander Ghindin, Diemut Poppen, Francoise Groben, Gary Hoffmann, David Grimal, Lawrence Power, Paul Meyer, Francois-Frederic Gui, Laurent Korcia and Tedi Papavrami.

Peter Laul has recorded for Harmonia Mundi, Aeon, Onyx, Naxos, Marquis Classics, Querstand, Integral Classics, King Records, Northern Flowers and numerous TV and radio stations in Russia and abroad.