Artist Led, Creatively Driven

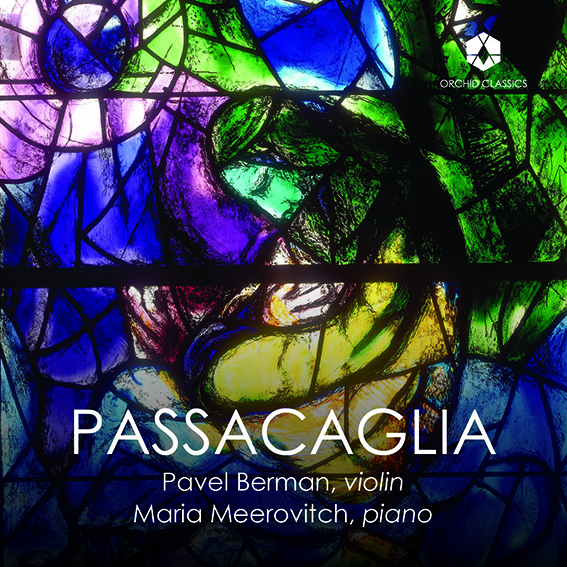

Passacaglia

Pavel Berman, violin

Maria Meerovitch, piano

Release Date: October 6th

ORC100262

Passacaglia

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936)

Violin Sonata in B minor, P.110

1. I Moderato

2. II Andante espressivo

3. III Allegro moderato ma energico

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Violin Sonata in G major, Op.134

4. I Andante

5. II Allegretto

6. III Largo

Pavel Berman, violin

Maria Meerovitch, piano

Ottorino Respighi is best known for his Roman trilogy: Fountains of Rome (1916), Pines of Rome (1924) and Roman Festivals (1928), three orchestral tone poems of extraordinary imagination, so bombastic and colourful that they have tended to overshadow his smaller-scale works, such as the Violin Sonata of 1917.

Respighi showed an early aptitude for the piano, becoming proficient after a few lessons from his piano teacher father, Giuseppe. One account describes how Giuseppi, ‘coming back home earlier than usual one day, was surprised to hear on the stairs that someone was playing Schumann’s Variazione sinfoniche; none of his pupils was studying that piece, and immense was his surprise when he found Ottorino sitting at the piano, for he has not imagined that his son could have acquired such a level of skill through the few, sporadic lessons he had given him.’

Respighi went on to study violin and composition at Bologna’s Liceo Musicale. While working as an orchestral viola player in Russia, he briefly studied with Rimsky-Korsakov, which influenced his orchestration, although lessons with Bruch in Berlin were less fruitful. Back in Bologna, Respighi played in orchestras and transcribed scores. He moved to Rome in 1913 to become professor of composition at the Liceo Musicale di Santa Cecilia, marrying his student, Elsa Olivieri Sangiacomo, in 1919. International fame brought travel and the approval of Mussolini, who nevertheless sided with modernists against Respighi and his colleagues when, in 1932, they urged a return to Italian traditions.

By the time Respighi had arrived in Rome in 1913, the city had consolidated its position as Italy’s cultural capital. This inspired him to compose Fountains of Rome which, though not instantly as successful as it would become, proved to be a pivotal moment in his career. The Violin Sonata dates from the period directly after the tone poem’s composition, when Respighi was yet to appreciate the significance of his own achievement. Consequently, he took his time deciding which stylistic direction to pursue, and the Violin Sonata reflects this in its range of vocabulary, from Romantic idioms suggesting the influence of Franck and others, to the academic prowess of the final passacaglia.

This was Respighi’s first large-scale chamber composition since his attempted string quartet of 1909, but there is no hesitancy in his assured treatment of two contrasting themes: an expansive, heartfelt violin melody over sombre accompaniment, and a softer theme that is sweet and seductive without being cloying. The airy central movement is closer in feel to the impressionism of Respighi’s orchestral output, opening with gloriously relaxed, almost improvisatory piano writing before the violin unfolds a melody that seems to radiate Italian light.

Then comes the vigorous final movement. A passacaglia, like a chaconne, is structured around a recurring line: in a chaconne this is restricted to the bass, but in a passacaglia the recurring theme may be used in other parts of the texture. Respighi’s is a powerful, Brahmsian example, showing the weighty technique that underpinned his music; but with characteristic flair he varies the mood by lightening the texture to create witty contrast, or by unfurling a leisurely, romantic passage that slowly darkens, returning us to the opening atmosphere for a dramatic coda.

The first performance in Bologna in 1918, performed by Respighi’s former teacher Federico Sarti with the composer as the piano, was a success. Respighi wrote afterwards: ‘Praise be! I shouldn’t say so, but we played it well. Me included!’ A subsequent performance in Chicago in 1923 prompted a review in the Chicago Daily Tribune declaring that ‘this sonata served to indicate how the new generation of Italian composers is labouring to get away from the theory that Italian music means Italian opera … Respighi has written rather a good sonata … conceived along broad lines and on large ideas.’

It was about a decade later that Shostakovich and the great violinist David Oistrakh first met, in the mid-1930s. This was at around the time of Shostakovich’s denunciation in the state newspaper, Pravda – just one of a litany of state persecutions he endured alongside, giddyingly, moments of being paraded about as their spokesperson. Oistrakh had been hoping for a concerto from his friend for some time and was eventually rewarded with Shostakovich’s First Violin Concerto. The Second Violin Concerto followed much later, in 1967 – intended as a 60th birthday present to Oistrakh. But Shostakovich was a year out, as Oistrakh explained:

‘Dmitri had been wanting to write a new, second concerto for me as a present for my 60th birthday. However, there was an error of one year in his timing. The concerto was ready for my 59th birthday. Shortly afterwards, Dmitri seemed to think that, having made a mistake, he ought to correct it. That is how he came to write the Sonata … I had not been expecting it, though I had long been hoping that he would write a violin sonata.’

Shostakovich completed the Violin Sonata in G in the autumn of 1968, and Oistrakh gave the premiere in May 1969 at the Moscow Conservatory. These were years of ill health for Shostakovich; he was diagnosed with polio in 1965, and the Sonata was composed as he recovered from breaking his right leg in September 1967 (having broken the left at his son Maxim’s wedding in 1960). As he wrote wryly to his friend, the critic and librettist Isaac Glikman: ‘Target achieved so far: 75 per cent (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective)’. He missed the premiere of the Second Violin Concerto as a consequence.

There was a silver lining to this particular cloud, however, which was that Shostakovich, with no hope of publicly playing the Violin Sonata’s piano part himself, indulged in some of his most virtuoso writing since his First Piano Sonata. He admitted to Glikman that he had attempted these challenging passages while rehearsing with Oistrakh and had found the strain ‘awful’. Nevertheless, he and Oistrakh made an informal recording together, after which came some unofficial performances – with other pianists – before the work’s official premiere.

The Violin Sonata is a formidable work. Shostakovich’s preoccupation with his own mortality at this time spawned an interest in a new and bracing range of procedures, including his own take on the 12-tone techniques – with their wide-ranging harmonic implications – pioneered by the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg and Webern). True enough, the Sonata’s first movement begins with a tone-row for the piano in octaves and, while the work is not strictly ‘serial’ throughout, Shostakovich’s flexible approach to meter during the movement allows for the row to undergo different permutations. The influence of Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata No.1 – which had been premiered by Oistrakh – is also palpable. The movement ebbs and flows between remote otherworldliness and surges of threatening tension, with surprising contrast created by a characteristically sardonic little dance that starts with a childlike melody on the piano.

The second movement also includes an injection of humour – of a kind – when a waltzing ‘trio’ section abruptly interrupts the muscular scherzo, but things become increasingly unhinged with toy-box piano writing and wailing violin lines. The final movement, in common with that by Respighi, is a passacaglia, although of a very different nature. The theme is unveiled on pizzicato violin, like some ghostly memory, answered by hypnotic piano writing. Bar occasional interruptions, the theme threads its way through the whole movement, culminating in a cadenza-like section for the violin. The introductory material is reprised, and there are references to the first movement including ‘sul ponticello’ (near the bridge) writing for the violin. There are brief outbursts from both instruments and shivering death rattles from the violin before the music, almost imperceptibly, dies away.

© Joanna Wyld, 2023

Pavel Berman

Violin

Pavel Berman attracted international attention when he won Second Prize at the 1987 Paganini Competition at the age of 17, and received First Prize and the Gold Medal at the 1990 Indianapolis International Violin Competition.

He has performed as both a soloist and conductor with orchestras such as the Moscow Virtuosi, i Virtuosi Italiani, Orchestra RAI di Torino, Orchestra di Santa Cecilia, Moscow Symphony Orchestra, Romanian National Radio, Prague Symphony Orchestra, Staatskapelle Dresden, Berliner Symphoniker, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Beijing Philharmonic Orchestra and Tokyo Philharmonic, among others. Mr. Berman has performed in prestigious halls such as Carnegie Hall in New York, Théâtre des Champs Elysées and the Salle Gaveau in Paris, Herkulessaal in Munich, Auditorio Nacional de Música in Madrid, Bunkakaikan and Suntory Hall in Tokyo, and Teatro alla Scala in Milan.

In 1998, Mr. Berman founded the Kaunas Chamber Orchestra in Lithuania and was its artistic director until 2005. He took part in the Rachmaninoff project presented at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia and at the Festival Settimane Musicali di Stresa.

He has collaborated with musicians such as Lazar Berman, András Schiff, Bruno Canino, Alexander Rudin, Eliahu Inbal, Daniel Oren, Shlomo Mintz, Alban Gerhardt, Donald Weilerstein. Additionally, he has recorded for Koch International, Audiofon, Discover, Phoenix Classics, and Dynamic. He currently gives masterclasses in numerous academies and is regularly invited to participate in the juries of the Paganini International Competition, the George Enescu International Competition, the Isang Yun Competition, Classical Strings and many others.

In 2021, Mr. Berman became the co-founder and artistic director of the Monteverdi Circle Online Centre for the Performing Arts. Pavel Berman is currently a professor in Conservatorio della Svizzera Italiana in Lugano, Switzerland, and in Accademia Perosi in Biella, Italy.

Among his former students are such artists as the recent winner of The Paganini Competition, Giuseppe Gibboni, the concertmaster of La Scala Orchestra, Laura Marzadori, the winner of ICMA 2022 prize, Gennaro Cardaropoli, and many other violinists who have taken leading positions in orchestras.

Pavel Berman was born in Moscow in 1970. He studied at the Central School of Music and the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory with Igor Bezrodniy and then went to the Juilliard School in New York to study with Dorothy DeLay and later with Isaac Stern. He plays an Antonio Stradivari violin, Cremona 1702 ‘ex David Oistrakh’, kindly lent to him by the Fondazione Pro Canale in Milan.

Maria Meerovitch

Piano

Belgian pianist Maria Meerovitch was born in St. Petersburg to a non-musical family. Nevertheless, music has been an important part of her family’s life, and at the age of six Maria began her musical education. At the age of eight she performed at St. Petersburg Philharmonic Hall for the first time.

She continued her studies at St. Petersburg Conservatory’s junior Music Institute with M. Freindling and M. Lebed and later under Prof. Anatol Ugorski at the Rimsky-Korsakov St. Petersburg State Conservatory, with piano as her principal subject.

In 1990 Maria came to Belgium after having received a scholarship from “Fonds Alex de Vries” – Y. Menuhin Foundation, graduated from the Royal Conservatory of Antwerp (cum laude), and immediately began teaching piano and chamber music at the same institution. She subsequently won first prizes at several International Competitions (G.B. Viotti, Italy; Ch. Hennen, the Netherlands) and has been performing around the world ever since appearing in solo and chamber music recitals in the USA, Japan, Taiwan, Brazil, The Republic of South Africa, South Korea, Israel, and Europe. Highlights include Concertgebouw (Amsterdam), Bad-Kissingen Musik Festival, Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, Trans Siberian Art Festival (Novosibirsk), Cité de la Musique (Paris), Opera City Hall (Tokyo), Laeiszhalle (Hamburg), Newport Music Festival (Newport), Dvorák International Music Festival (Prague), Martha Argerich’s Meeting Point (Beppu), Théâtre des Champs Élysées (Paris), National Center for the Performing Arts (Beijing), Pharos Chamber Music Festival (Cyprus), Elbphilharmonie (Hamburg), Heidelberg Frühling festival (Heidelberg), Progetto Martha Argerich (Lugano), Teatro Municipal (Rio de Janeiro), Moritzburg International Festival (Moritzburg), St.Petersburg Philharmonic Hall, Rudolfinum (Prague), etc.

She has collaborated and made a number of recordings (to name a few: Arte-TV, Mezzo-TV, Teldec-classics, Naxos) with a variety of international chamber music partners: Martha Argerich, Pinchas Zukerman, Philippe Hirschhorn, Saulus Sondeckis, Maxim Vengerov, Vadim Repin, Daniel Hope, Dmitry Sitkovetzky, Dora Schwarzberg, Boris Berezovsky, Sergei Nakariakov, Daishin Kashimoto, Christian-Pierre La Marca, Pavel Berman, Boris Brovtsyn, etc.

As a soloist, Maria has appeared with numerous orchestras around the globe including London Philharmonic Orchestra, Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, Taiwan National Symphony Orchestra, Schleswig-Holstein Festival Orchestra, The English Chamber Orchestra, Deutsche Radio Philharmonie, and many others.

Maria’s research on a subject related to the treatment of severe tendonitis during piano playing amongst professional musicians, a list of exercises, based on her own experience and full recovery, made a significant change in her daily work as a piano instructor. Her present lectures on a subject connected to “Stage Fright” research has received a significant response from professional musicians.