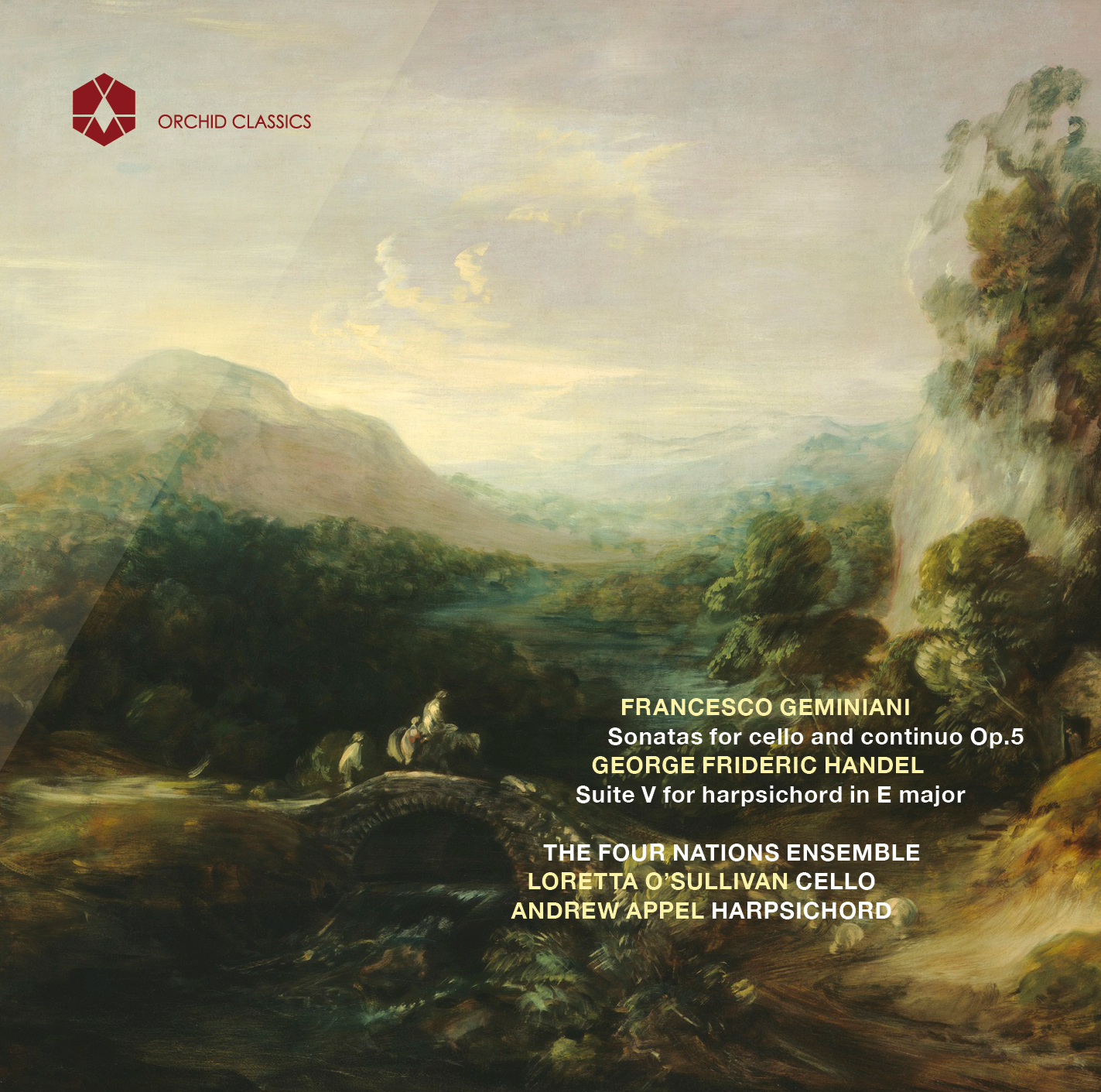

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Geminiani and Handel Sonatas

Andrew Appel and Loretta O’Sullivan

The Four Nations Ensemble

Release Date: 1 June 2015

ORC100049

FRANCESCO SAVERIO GEMINIANI (1687-1762)

Six sonatas for violoncello e basso continuo, Op.5 (1746)

Sonata II in D minor

1 Andante 2:41

2 Presto 2:54

3 Adagio 0:52

4 Allegro 4.58

Sonata I in A major

5 Andante 2.22

6 Allegro 4:09

7 Andante 0:53

8 Allegro 4.30

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685-1759)

Suite V in E major, HWV430 (from Suites de Pieces de Clavecin Composées par… 1720)

9 Prélude 2:20

10 Allemande 5:23

11 Courante 2:10

12 Air 0:53

13 Double 1 0:36

14 Double 2 0:45

15 Double 3 0:40

16 Double 4 0:45

17 Double 5 0:56

FRANCESCO SAVERIO GEMINIANI

Sonata III in C major

18 Andante 1:57

19 Allegro 5:00

20 Affetuoso 3:46

21 Allegro 3:08

Sonata IV in E flat major

22 Andante 0:28

23 Allegro Moderato 2:00

24 Fantasia at lib. é poi da capo 2:12

25 Grave 0:52

26 Allegro 1:02

Sonata V in F major

27 Adagio 0:41

28 Allegro moderato 1:34

29 Adagio 2:57

30 Allegro 3:04

Sonata VI in A minor

31 Adagio 0:47

32 Allegro assai 3:39

33 Grave 0:37

34 Allegro 4:37

THE FOUR NATIONS ENSEMBLE

Loretta O’Sullivan cello

Andrew Appel harpsichord

Beiliang Zhu continuo cello

Scott Pauley theorbo and guitar

The solo and trio sonatas of Italian violinist and composer Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) were something of a creative irritant in 18th century Paris. In London, however, where the English ear had tuned itself to the Italian sonata and concerto, Corelli’s concerti were accepted as the unquestioned standard for fine instrumental composition. Indeed, his Opus 5 and 6 offered the very definition of good taste. Thus, it was on the Italian concerti that such English composers as William Boyce (1711−1779) and Thomas Arne (1710−1778), more reverent than the French — or the Germans, for that matter — modelled their works. And so it followed that any foreign composer who wanted to make a mark on the English ear did so with Corellian sounds. How wise, then, that Italian violinist, composer and music theorist Francesco Geminiani (1687–1762), once he was established in London and looking to entice local audiences, took the solo violin sonatas of Corelli’s Op. No.5 and retooled them as concerti.

The English amateur of the day, wealthy and prepared to spend liberally on the paintings of Giovanni Antonio Canal (Canaletto) and the voice of famed castrato Carlo Broschi (Farinelli), wanted Italian instrumentalists and composers to occupy the stages, pits and music rooms of London. A student of Corelli, Geminiani should have had a brilliant career. Yet somehow he didn’t.

For a contemporary view, we usually look to Charles Burney (1726−1814), the English organist, composer and preeminent music historian of his time. Had he been of a generous spirit, Burney might have told us that Francesco Geminiani marched, or composed, to a different drummer. And there is evidence, quite literally, to support such an understanding: Geminiani seems to have lost a post as concertmaster in Naples because he could not set a pace to guide the rest of the ensemble. Burney’s A General History of Music notes:

“…And having finished his studies (in Rome), he went to Naples, where from the reputation of his performance at Rome, he was placed at the head of the orchestra but according to the elder Barbella he was soon discovered to be so wild and unsteady a timest, that instead of regulating and conducting the band, he threw it into confusion; as none of the performers were able to follow him in his tempo rubato, and other unsuspected accelerations and relaxations of measure.”

Later, when Geminiani had achieved some degree of fame, it seems that other musicians, too, found it difficult to accompany him. His rubato was still felt to be excessively fluid and irregular. Finally, and most importantly, try reading through almost any allegro movement in Geminiani’s Op.5 sonatas, and you, too, may find yourself puzzled. Again, in Burney’s words (Ibid.):

His second set of solos, commonly called his French Solos, either from their style or their having been composed and engraved in France, was published in 1739. These were admired more than played…his third set of concertos…was so laboured, difficult and fantastical as never to be played, to my knowledge, in either public place or private concert.

Perhaps, then, Burney was right to fault Geminiani’s musicianship. Certainly he did not enjoy an easy career and did not gain the fame and high market esteem that other Italians in England seemed to have garnered. He was not, however, insulted by every critic and historian. Sir John Hawkins (1719–1789), in his History of the Science and Practice of Music, assesses Geminiani rather differently:

“In the year 1714 [Geminiani] came to England, where in a short time he so recommended himself by his exquisite performance, that all who professed to understand or love music, were captivated at the hearing of him….”

And again, from the same work:

“In the year 1716 he published….twelve sonatas, a violin violone e cembalo…The publication of this work had such an effect that men were at a loss to determine which was the greatest excellence of Geminiani, his performance or his skill and fine style in composition.”

Finally, Hawkins arrives at the major issue (Ibid.):

“It is observable upon the works of Geminiani, that his modulations are not only original, but that his harmonies consist of such combinations as were never introduced into music till his time: the rules of transition from one key to another which are laid down by those who have written on the composition of music, he not only disregarded, but objected to as an unnecessary restraint on the powers of invention. He has been frequently heard to say, that the cadences in the fifth, the third and the sixth of the key which occur in the works of Corelli, were rendered too familiar to the ear by the frequent repetition of them; And it seems to have been the study of his life, by a liberal use of the semitonic intervals, to increase the number of harmonic accompaniment…

Geminiani’s rejection of this harmonic language, a language that gives clear direction to Corelli and boundless energy to Vivaldi, gives his allegros an entirely different character, a quality of search and experimentation. For the modern listener, now well accustomed to the vitality and clarity of the Italianate sonata and concerto of the 18th century, this can be confusing. Burney found it weak; Hawkins found it fascinating. Today, three centuries later, we are in a position to embrace the rich repertory of these 18th century masters, and to happily enjoy the varied approaches they took to creating musical experience, as well as the challenges and satisfactions we discover we have inherited from them.”

© Andrew Appel 2015

A NOTE FROM LORETTA O’SULLIVAN

In preparing to record these sonatas, I kept a few essential ideas in mind. Geminiani encouraged the performer to be moved by the music and to be generous in expression. In his violin tutor, The Art of Playing the Violin (1751), he speaks of creating a tone that rivals the voice, and offers examples of varied bowings and vibrato to support the expression of affect. The way we play an ornament, he tells us, can express any emotion—from “mirth to horror.”

Geminiani opposed routine stress on downbeats, encouraging the performer to seek out the musical line before exerting an accent. In fact, his composition often seems to lead us away from such habits. As we worked on these movements, it seemed best to avoid regularity where the music went on imaginative tangents. We could then embrace evident accents and cadences.

I put myself in the shoes of a dreamer, one who enjoys excursions, oddities and surprises. Without imposed weight, one can stroll through a subtly changing terrain. Sometimes, as in the Allegro Assai of Sonata VI, the motives tumble on top of each other in a quirky and frantic way. Then the bass line suddenly disappears, leaving the cello in momentary free-fall, caught up an instant later. The final Allegro of this sonata puts all in balance with a pair of colourful minuets.

Perhaps the most inventive of all is Geminiani’s through-composed Sonata IV. In the Allegro Moderato, flourishes of dotted rhythms and bass-line snippets comically interrupt the cello’s efforts to extend a complete thought. Geminiani gives the cello some relief in a virtuosic section that ends in a grand cadence. He then invites the soloist to take free creative rein in a fantasy ad lib. A short Grave using extreme dynamics and rolling arpeggios is followed by a beautiful French dance.

His slow movements, such as that of Sonata III, combine sung Italian and ornamented French styles. In each repetition of his wistful melody, Geminiani suggests a slight variation of embellishment, showing how delicate one can be in expressing an affect. Other andantes cover a range of colour and expression from painful darkness to welcoming warmth.

Suite in E major by G.F. Handel

Handel performed with Geminiani in London. With that in mind, and inspired by the magnificent Kirckman harpsichord of 1754 that you hear in this recording, we offer the popular Suite in E Major from the Eight Great Suites of Handel. Unlike Geminiani, Handel was comfortable, satisfied and brilliant in the harmonic language of Corelli. Here, he combines the energy and lyricism that are his trademark, giving us a suite that moves consistently, gracefully and masterfully from the contemplative to the songful to the ebullient. This work benefits from the tonal possibilities of the mid-18th century English instrument, too often overlooked today in favour of models from other schools and countries.

Andrew Appel

This recording is dedicated to the memory of our friend and patron, Ellie Warburg, who missed no opportunity for joy and was responsible for much of the joy in the preparation and recording of these sonatas.

Harpsichord: Jacob Kirckman 1754, generously lent from a private collection

Recorded August 13-16, 2013, Hamden Connecticut, USA

Produced by Karen McLaughlin and David Walters

Recorded by David Walters

Artist photo David Rodgers

French translation Laurent Rapin

Cover painting Gainsborough, from the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

LORETTA O’SULLIVAN

“an agile, eloquent player”

New York Times

Ms. O’Sullivan, who performs on Baroque, Classical and modern cello, is one of America’s most honoured and valued continuo players and is equally admired for her poetic and refined interpretations of the solo cello repertory from its earliest days through the 19th century. She has played key roles in chamber ensembles including the Four Nations Ensemble, The Haydn Baryton Trio and the Classical Quartet. In concert and recording Ms. O’Sullivan has given memorable performances of music by Frescobaldi, Caldara, Porpora, Leclair, Handel, Haydn, Schobert, Mozart and Beethoven, performing cello sonatas, concertos, trio sonatas, arias with cello obbligato, string quartets and virtually every form and format in three centuries of well known and rarely heard music.

Ms. O’Sullivan also plays key roles in American music making as continuo cellist for both Opera Lafayette with whom she has performed works of Philidor, Monsigny and Francouer at the Opera de Versailles as principal cellist. She is continuo and principal cellist for the Bach Choir of Bethlehem, one of America’s most venerable musical organizations. On modern cello, Ms. O’Sullivan is heard with the St Luke’s Orchestra in New York.

Ms. O’Sullivan has performed at halls including Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, Merkin Concert Hall, the New York Historical Society, Columbia University, Yale University, London’s Wigmore Hall, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England, and Esterhazy Palace in Austria and in festivals including Mostly Mozart in New York, Ottawa Chamber Music Fest, the New England Bach Festival and New Haven’s Festival of Arts and Ideas.

As a teacher and lecturer Ms. O’Sullivan has participated in residencies for university students as well as arts in education programmes for children from 5 to 18 years old. Loretta gave a pre-concert lecture for Yo-Yo Ma’s performance of the Bach Cello Suites in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and has given performance practice master classes at Brooklyn College, the University of Iowa, Memphis State University, and the University of Wisconsin. She has coached baroque cellists at Rutgers University, Mannes School of Music, and The Juilliard School.

Previous recorded solo performances include sonatas of Vivaldi and Porpora as well as her own transcription of the Biber Passacaglia.

ANDREW APPEL

Andrew Appel, Artistic Director of the Four Nations Ensemble, performs throughout Europe and the United States as soloist in many festivals including Italy‘s Spoleto Festival, New York‘s Mostly Mozart Festival, and the Redwoods Festival. As recitalist, Mr. Appel has performed at Carnegie and Avery Fisher Halls in New York, as well as halls from the Music Academy of the West to the Smithsonian in Washington DC. Besides his work with The Four Nations Ensemble he has been a guest of Chatham Baroque, the Smithsonian Players, and Orpheus. He serves as harpsichordist for Opera Lafayette and has toured with several European chamber orchestras. He has enjoyed critical acclaim for his solo recording of Bach works with Bridge Records as well as his fortepiano performances of Haydn for ASV. He has recorded for ASV, Bridge, and Smithsonian recordings and is presently recording the complete harpsichord works of Francois Couperin for Orchid Classics.

As an educator Appel has been called upon to create significant programmes in arts education for elementary school students and professional development for teachers.

As a writer Mr. Appel has written programme notes and articles for presenters around the country including Lincoln Center, New Jersey Performing Arts Center, and National Public Radio. Mr. Appel has participated in discussions on education and chamber music programming at conferences of Chamber Music America, the Association of Performing Arts Presenters, and the New York State Council on the Arts. He currently serves as President of the Board of Trustees of Chamber Music America. He has been regularly praised for pre-concert talks that contextualize the music and open areas of discovery for the audience.

A native of New York City, Appel discovered the harpsichord at 14. First-prize winner of the Erwin Bodkey Competition in Boston, he holds an international soloist degree from the Royal Conservatory in Antwerp where he worked with Kenneth Gilbert and a Doctorate from the Juilliard School under Albert Fuller. There he has taught harpsichord and music history. Appel has also taught harpsichord, chamber music, music history and humanities courses at Moravian College, Princeton University, and New York Polytech, now a division of NYU.

BEILIANG ZHU

Beiliang Zhu won the first prize and the Audience Award at the XVIII International Bach Competition in Leipzig 2012 (Violoncello/Baroque Violoncello) as the first string player to have received this honour on a baroque instrument. Hailed by the New York Times as “particularly exciting”, and by the New Yorker as bringing “telling nuances” and being “elegant and sensual, stylishly wild”, Beiliang seeks artistry in a wide range of repertoire and different roles as a modern cellist, baroque cellist, and violist da gamba. She has given solo recitals at the Bach Festival Leipzig, Boston Early Music Festival, the Seoul Bach Festival, the Helicon Foundation, among others, as well as performing with internationally acclaimed artists and ensembles. Fascinated by studies of cultures, Beiliang believes firmly in the communicative qualities of musical performances therefore invites the listeners to converse with her through various means.

SCOTT PAULEY

Scott Pauley holds a doctoral degree in Early Music Performance Practice from Stanford University. Before settling in Pittsburgh in 1996 to join Chatham Baroque, he lived in London for five years, where he studied with Nigel North at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. There he performed with various early music ensembles, including the Brandenburg Consort, The Sixteen and Florilegium. He won prizes at the 1996 Early Music Festival Van Vlaanderen in Brugge and at the 1994 Van Wassenaer Competition in Amsterdam. In North America Scott has performed with The Four Nations Ensemble, Tempesta di Mare, Musica Angelica, Opera Lafayette, The Folger Consort, The Toronto Consort, and Hesperus and has soloed with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. He has performed in numerous Baroque opera productions as a continuo player, both in the USA and abroad. He performed at Carnegie Hall in New York and at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, with the acclaimed British ensemble, the English Concert.

“the players allow Geminiani’s unique lines to take shape, to the frequent surprise and delight of the listener. The opening Andante feels as if Loretta O’Sullivan were singing through the cello, while in faster, more ornamented movements the collaboration between the cello and the harpsichord is unified and witty.” – Early Music America