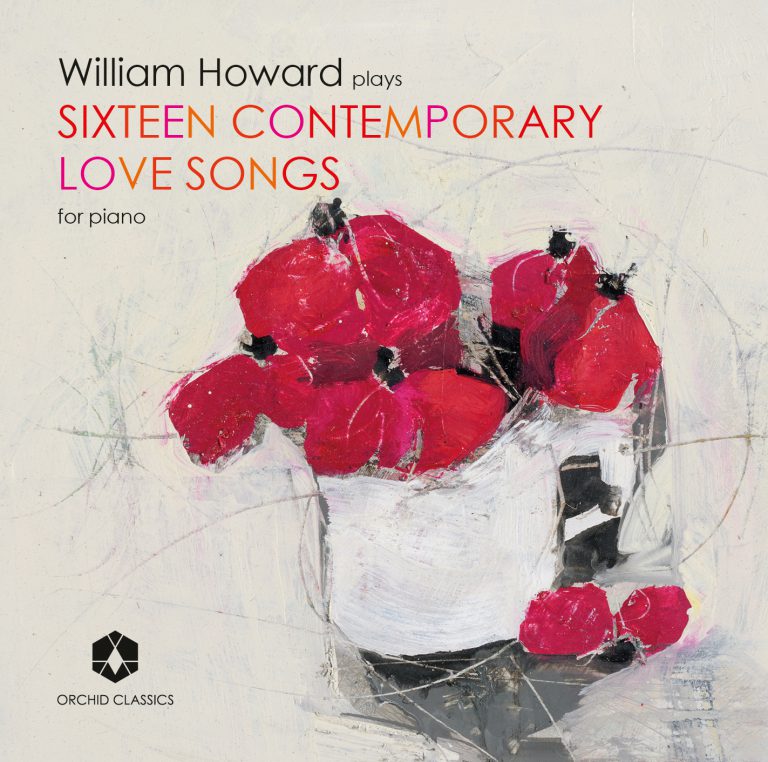

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

William Howard Plays

Sixteen Love Songs

For Piano

Release Date: 1st June 2016

ORC100056

Sixteen Love Songs

1 Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) arr. Franz Liszt (1811-1886) 4.13

Auf Flügeln des Gesanges (On the Wings of Song)

2 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) arr. Liszt 5.42

Ständchen (Serenade)

3 Robert Schumann (1810-1856) arr. Liszt 4.16

Widmung (Dedication)

4 Franz Liszt 4.42

Liebestraum (Love’s Dream) No.3

5 Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) 2.19

Láska (Love) from Bagatelles and Impromptus (1844)

6 Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) 5.40

Serenáda (Serenade) from Poetic Tone Pictures Op.85

Zdeněk Fibich (1850-1900)

7 No.44 (Op.41/I) Andante 3.17

8 No.36 (Op.41/I) Andante amoroso 2.12

9 No.139 (Op.41/IV) Lento (Poème) 1.35

10 Vítěslav Novák (1870-1949) 3.38

Serenáda (Serenade) Op.9 No.3

11 Josef Suk (1874-1935) 7.01

Píseň Lásky (Love Song) Op.7 No.1

12 Janáček (1854-1928) 3.22

Lístek Odvanutý (A Blown Away Leaf) from On An Overgrown Path

13 Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) 2.37

Romance sans Paroles (Romance without Words) Op.17 No.3

14 Enrique Granados (1867-1916) 6.48

Quejas ó la Maya y el Ruiseñor (Laments, or The Maiden and the Nightingale) from Goyescas

15 Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962) arr. Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 5.06

Liebesleid (Love’s Sorrow)

16 Richard Strauss (1864-1949) arr. Max Reger (1873-1916) 4.00

Morgen (Tomorrow)

Total time 66:30

William Howard – Piano

Sixteen Love Songs

The pieces in this collection are all songs, some originally written for piano and others arranged. They are all expressions of love of some kind and thus share common ground with a huge body of folk and popular music. Romance is universal in life and music; yearning, dreaming, passionate declarations of love and devotion, and the sorrow of lost love have been expressed in music over the centuries and throughout the world. The 16 love songs in this collection are all beautifully constructed examples of ‘art’ music, written throughout the 19th century or at the beginning of the 20th by composers who had a great understanding of the expressive possibilities of the piano and the power to seduce the listener. Some of them have become massively well known through film scores or TV ads, or even become popular songs in an adapted form.

Particular pieces inspired me to put this collection together. It was over 30 years ago that I bought an old second-hand copy of Josef Suk’s Love Song in a music shop in Prague on one of many visits to communist Czechoslovakia. I fell in love immediately with this gorgeous, passionate piece and wondered why it was not better known. At the same time I started including in my recital programmes works by another Czech composer, Zdeněk Fibich. He was almost entirely unknown to audiences in the UK in the 1980s, and yet after everyperformance some older members of the audience would always come backstage to ask why one of the pieces was so familiar. It took me several years to find out that Fibich’s Poème had been a popular hit in the 1930s with the title My Moonlight Madonna. Czech composers of the late 19th century and early 20th made particularly touching personal or autobiographical statements in music, which is how half of these 16 songs come to be from Czechoslovakia. Schubert’s Serenade has always haunted me (and I love Liszt’s reverent arrangement of the song) and so too Granados’s heart-rending lament The Maiden and the Nightingale. Many other of the pieces have been favourite concert pieces of mine for decades.

The collection also arose from my love of the piano itself. I have always enjoyed the challenge of playing music that requires a beautiful and lyrical sound on what is sometimes dismissed as a percussion instrument. Many of the pieces I have chosen here (for instance the four Liszt arrangements that open the album) are inspiring to play because they are so imaginatively conceived for the instrument, even if they are by no means easy. Much as I enjoy performing with singers or with other instrumentalists, I also appreciate the fact that we pianists can at times have all the music to ourselves, both the melody lines and every different kind of accompaniment that might go with them.

The album starts with four arrangements by Liszt of songs originally written for voice and piano.The first is an adaptation of one of Mendelssohn’s best known melodies On the Wings of Song (Track 1), a langorous setting of a poem by Heine, describing a dream of blissful undisturbed love in an exotic location (a garden of red flax by the Ganges!). Mendelssohn composed the song in 1836 around the time when he became engaged to his future beloved wife Cécile. The mood of the song reflects more the sensuality of the poem than its exotic location, and Liszt, in his magical piano adaptation, heightens the passionate mood still further.

Schubert’s Serenade (Track 2) is a song of a lover’s yearning and pleading, with a bittersweet flavour. Schubert’s gift for melody and his affinity with the German romantic poets of his day gave rise to over 600 songs in the course of his short lifetime. Serenade was one of his last,written in August 1828, just three months before his death at the age of 31. Liszt’s arrangement is respectful of the original but full of pianistic imagination.

Widmung (Track 3) was Schumann’s ‘Dedication’ to Clara, the love of his life. It was written in 1840, the year in which the couple were finally able to get married after five years of opposition on the part of Clara’s father, Schumann’s former teacher. Widmung was the first and most passionate of a collection of songs that Schumann wrote as a wedding present to his bride.

The music expresses his most heartfelt feelings of devotion and passion. At the end of the song he quotes directly from Schubert’s Ave Maria, another famous song of devotional love. In his arrangement of Schumann’s song Liszt takes great liberties with the original, expanding the range and scale of the piano writing to heighten the ardent mood of the song.

Liszt’s Liebestraum No.3 (Track 4) is an arrangement of a song of his own, written in 1843 when he was at the height of his fame, touring Europe like a pop-star and giving piano recitals that aroused frenzied reactions among his audiences, with women swooning, fans fighting over souvenirs and honours heaped upon him from all directions. The poem that he set in the original song is an exhortation to love unconditionally until separated by death. In his virtuosic piano version, which has outstripped the original song in popularity and become one of his best known works, Liszt creates an impassioned piece, which starts wistfully, erupts into a tumultuous outburst of emotion in its central verse, and subsides into resignation at its end.

The next eight pieces are all by Czech composers. Smetana was a love-stricken 20-year-old student in Prague when he wrote Láska (Love) (Track 5) in 1844, one of a collection of pieces he called Bagatelles and Impromptus, whose other titles (Dejection, Idyll, Desire, Joy etc) betray his preoccupation with Kateřina, a fellow music student and duet partner, for whom he composed a number of piano works.They were also keen dancing partners, so it is no surprise that this love song takes the form of a gentle waltz. The warmth, simplicity and innocence of this short piece by the young Smetana are the more touching in the light of subsequent events. Although he and Kateřina were eventually able to marry five years later, they lost three of their four children before Kateřina herself died of tuberculosis ten years into their marriage.

Smetana’s compatriot Dvořák is much loved for music that is full of song and dance and infused with the flavour of Czech folk music, but his colourful and beautifully written piano music has been strangely neglected. His alluring Serenade (Track 6) is one of 13 pieces published as Poetic Tone Pictures that he wrote in a six-week period in 1889. It was a time of his life when he was returning to some of the music of his youth. In 1887 he made a string quartet arrangement, published with the title of Cypresses, of a cycle of love songs that he had written as a 24-year-old for a student, Josefína Čermáková, with whom he had become infatuated. Josefína did not respond to Dvořák’s attentions and married another man. Eight years later Dvořák married her younger sister, Anna, with whom he had six children, but there is evidence to suggest that Josefína always remained the love of his life.

Of all the Poetic Tone Pictures the Serenade is closest in spirit to the love songs, but since it has no known reference outside of the music itself,we can only speculate as to what inspired this hauntingly atmospheric piece.

Fibich is a largely forgotten composer now, but in his prime enjoyed much success both at home and abroad. The three pieces recorded here (Tracks 7, 8 and 9) belong to an erotic diary that forms one of the most extraordinary collections of piano pieces ever written. In 1892 Fibich, after many years in a strained marriage with the sister of his deceased first wife, fell in love with a beautiful and talented pupil, Anežka Schulzová, who was 18 years his junior. The ensuing affair, which scandalised Prague, gave rise to several hundred short piano pieces, which include impressions of Anežka, reminiscences of events that the couple shared and intimate tributes to every part of her body. Three hundred and seventy-six of these pieces survive, published under the title Moods, Impressions and Souvenirs. The subject matter of most of the pieces has been indentified from annotations made by Fibich or by Anežka herself. No.44 (Track 7) describes Anežka wearing a violet dress and is one of the most passionate of a group of pieces describing her wearing different clothes. No.36 (Track 8) is an amorous love duet marked ‘Our harmony’. No.139 (Track 9) is dated 13 April 1893 and describes happy evenings spent with Anežka and her family on an island in the middle of Prague during their first warm spring together.

Vitěslav Novák is another Czech composer who wrote some fine music but was overshadowed by his more successful contemporaries. A pupil of Dvořák, he despaired at his own inability to forge a distinctive personal style in his music and, especially in his twenties, suffered from depression. Some success as a composer and happiness in love came to him later in his life, but his music is now seldom played. His hauntingly sad Serenáda (Track 10) is the third of a set of four serenades that he wrote in 1895, during his difficult years. A short and rather desperate poem is printed at the beginning of the piece: I cannot speak of my love, nor lean my cheek against yours. Only in song can I tell of you, of my love’s agony and of my ardent longing. One of the saddest and most touching expressions of emotion in the piano repertoire is a cycle of pieces by Josef Suk called O matince (‘About mother’), whch were written after the death of his wife for their five-year-old son. Suk was Dvořák’s favourite pupil and in 1898 married his daughter Otilie. After the death of Dvořák in 1904 and of Otilie the following year, Suk’s works took on a new seriousness and depth of expression. But before tragedy struck, his music had a carefree charm and easy romanticism, which earned him enormous popularity with the public at an early age. One of his best-loved works, the Love Song (Track 11) was written in much happier times while he was in his late teens.This extravagantly sensual and passionate piece was a favourite in concert programmes in Suk’s lifetime and can still be heard both in its original piano version and in various arrangements, most often for violin and piano.

Janáček’s A Blown Away Leaf (Track 12) comes from his cycle of piano pieces, On an Overgrown Path, which he wrote between 1900 and 1912. It was a period of great unhappiness for the composer, during which his only surviving child, Olga, died at the age of 19, and he and his wife were locked into a loveless marriage. Some of the later pieces of the cycle express his anguish following the death of Olga, but A Blown Away Leaf was one of the first to be written and predates the tragedy. The title suggests a fleeting mood, but the character of the piece, with its warm and innocent opening and subsequent eruptions of feeling, can be better understood when we learn that the composer first called it A Declaration of Love and then A Love Song before settling on this final version. Fauré’s Romances Sans Paroles were written while he was still a student in his late teens. His models were Mendelssohn’s much-loved Songs Without Words, but already in these short pieces, despite his young age, he has developed a grace and fluency that is entirely his own. The seductive charm of Fauré’s early music has sometimes distracted critics from the seriousness and emotional power of his larger-scale works. The American composer Aaron Copland described the Romance No.3(Track 13) as ‘the kind of indiscretion that every young composer commits’ and Fauré’s compatriot Debussy rather dismissively dubbed him a ‘master of charms’. But the restrained beauty and beguiling melody of this Romance has proved irresistible to generations of listeners, and, as always with Fauré, the real drama and passion is somehow concealed beneath the unruffled surface of the music.

Laments, or The Maiden and the Nightingale (Track 14) is the best-known work of the Spanish composer Enrique Granados and part of a cycle of piano pieces inspired by the paintings of Goya. Goyescas, subtitled Los majos enamorados (‘Gallants in Love’), was so successful after its premiere in 1911 that Granados went on to write an opera based on the work. In the opera the maiden sings her lament to a nightingale and tells of her fear that her lover will be killed in a duel with a rival. At the end of the song the nightingale’s reply can be heard. Granados instructed that this piece should be played ‘not with the grief of a widow but with the jealousy of a wife.’ The dedication of the movement to his wife Amparo makes this recommendation all the more intriguing.

In 1910 Fritz Kreisler, one of the greatest violinists of his time, gave a concert in Berlin, the programme for which included two posthumous waltzes by Joseph Lanner, an early 19th-century Viennese composer of dance music, together with his own Caprice Viennois.A critic of the Berliner Tageblatt reprimanded Kreisler for including his own ‘insignificant’ composition alongside the Lanner ‘gems’ and accused him of bad taste. Kreisler responded by confessing that the two waltzes, Liebesleid (‘Love’s Sorrow’) and Liebesfreud (‘Love’s Joy’) were actually written by himself and not by Lanner. Twenty-five years later it emerged that Kreisler had been performing a number of other pieces of his own in concerts that he had passed off as the work of other, often obscure composers, a mild deception which was seen as amusing by some critics and musicians and caused outrage to others.The two ‘Lanner’ waltzes became huge favourites with audiences throughout Kreisler’s long performing lifetime. Kreisler’s great friend Rachmaninov made his dazzling solo piano arrangement of Liebesleid (Track 15) in 1921, adorning the sweet-sad melody with virtuosic flourishes and dramatic eruptions and creating a favourite encore piece for his own recitals.

The last item on this recording is a simple and unadorned transcription by Max Reger of one of four songs that Richard Strauss presented to his bride Pauline on their wedding day in September 1894. Morgen (Track 16) is a serene and ecstatically beautiful evocation of undying and indestructible love. The couple’s relationship up to this point had been tempestuous to say the least, with frequent quarrels and break-ups. On the wedding day the groom was said to be phlegmatic and unflappable, while thebride was temperamental, fiery, tactless, rude and beguiling. Their stormy marriage was later commemorated, rather improbably, by Strauss himself in his opera Intermezzo (1924) in which the opening scene features a spectacular marital row. But despite all this turbulence, there must have been something of the spirit of Morgen in their relationship. The singer Lotte Lehmann said that after 25 years of marriage ‘there was a tie between them so elemental in strength that none of Pauline’s shrewish truculence could ever trouble it seriously’.

Morgen seems to tell of the calm at the heart of their strange but enduring union.

© William Howard 2016

WILLIAM HOWARD is established as one of Britain’s leading pianists, enjoying a career that has taken him to over 40 different countries. His performing life consists of solo recitals, concerto performances, guest appearances with chamber ensembles and instrumentalists, and regular touring with the Schubert Ensemble of London, Britain’s leading group for piano and strings and winners of the Royal Philharmonic Society Award for Best Chamber Ensemble. He can be heard on over 40 CDs, released by Chandos, Hyperion, ASV, NMC, Collins Classics, Black Box, Champs Hill and Nimbus.

His solo career has taken him to many of Britain’s most important festivals, including Bath, Brighton and Cheltenham, and he has been artist in residence at several others. He has performed many times at Wigmore Hall, the South Bank and at Kings Place in London and has broadcast regularly for BBC Radio 3. For many years he has been invited to perform and teach at the Dartington International Summer School. His recording of Dvořák Piano Works was selected as a Gramophone Critics’ Choice, and his recording of Fibich’s Moods, Impressions and Souvenirs won a Diapason D’Or award in France. His 2011 recording of Pavel Zemek Novák’s extraordinary 75-minute cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues, described by David Matthews as “one ofthe finest piano works of our time” received a double five-star review in BBC Music Magazine.

He is passionate about 19th-century piano repertoire, especially Schubert, Chopin, Schumann and Fauré. He also has a strong interest in Czech piano music, and has been particularly acclaimed for his performance of Janáček, for which he received a medal from the Czech Minister of Culture in 1986. Many leading contemporary composers have written for him, including Sally Beamish, Martin Butler, Piers Hellawell, David Matthews, Pavel Zemek Novák, Anthony Powers, Howard Skempton and Judith Weir.

www.williamhoward.co.uk

Producer: Jeremy Hayes

Engineer: Ben Connellan

Recorded at St. Silas the Martyr, Kentish Town, London

29 June to 1 July 2015

Piano: Steinway model ‘D’ 592087 from Steinway & Sons, London

Photography: Edward Webb

“A beautiful new recording of Sixteen Love Songs … how sensitively and expressively William Howard performs”

– John Brunning, Classic FM

“This poised, sensitively-played programme of ‘songs without words’ opens with Mendelssohn’s On the Wings of Song, but soon explores less well-charted waters.”

– BBC Music Magazine, 4*