Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Walton Façade

Carole Boyd, Zeb Soanes,

John Wilson

Release Date: 1st April 2017

ORC100067

SIR WILLIAM WALTON (1902-1983)

Façade. An Entertainment

Fanfare 0’31”

I

2 I. Hornpipe 1’11”

3 II. En Famille 2’55”

4 III. Mariner Man 0’34”

II

5 IV. Long Steel Grass 2’18”

6 V. Through Gilded Trellises 2’22”

7 VI. Tango-Pasadoble 1’54”

III

8 VII. Lullaby for Jumbo 1’39”

9 VIII. Black Mrs Behemoth 1’00”

10 IX. Tarantella 1’12”

IV

11 X. A Man from a Far Countree 1’27”

12 XI. By the Lake 1’52”

13 XII. Country Dance 1’48”

V

14 XIII. Polka 1’07”

15 XIV. Four in the Morning 2’07”

16 XV. Something Lies Beyond the Scene 0’54”

VI

17 XVI. Valse 3’06”

18 XVII. Jodelling Song 2’17”

19 XVIII. Scotch Rhapsody 1’09”

VII

20 XIX. Popular Song 1’54”

21 XX. Fox-Trot ‘Old Sir Faulk’ 1’49”

22 XXI. Sir Beelzebub 0’57”

Carole Boyd and Zeb Soanes, reciters

Ensemble 7×3

Joshua Batty (flute/piccolo); James Burke (clarinet/bass clarinet);

Howard McGill (alto saxophone); Alan Thomas (trumpet); Alex Neal (percussion); Richard Harwood and Pierre Doumenge (cellos)

Director: John Wilson

Frankly Speaking. Dame Edith Sitwell interviewed by Paul Dehn,

Lionel Hale and Margaret Lane.

Broadcast on the BBC Home Service on 25 November 1955 27’17”

23 Introduction…’what is the most beautiful line of poetry?’

24 Personal appearance 25 ‘…the technical side of your poetry…’

26 Façade 27 Thoughts on her early work 28 The Sitwell siblings…childhood 29 Other poets…poetry’s position in the world

30 Childhood reading 31 Façade again

32 Writing film scripts…America

33 Parental influence and childhood

34 Worst faults…battles against injustice…the aims of poetry

TT: 64’44”

It was while he was an undergraduate at Oxford University that William Walton first encountered the Sitwell family. Born to musical parents in the Lancashire town of Oldham in 1902, the young William had taken piano, violin and organ lessons, but it was for his singing voice that he was sent to Oxford with a scholarship to become a chorister at Christ Church. Although later he started working towards a Bachelor of Music degree, Walton was eventually to leave Oxford without graduating.

Having met his first Sitwell – this was Sacheverell, the youngest of Sir George Sitwell’s three children, who was then at Balliol – it was not long before he met his second, Osbert. Sacheverell, who already considered Walton, whose head he found ‘very intelligently shaped’, to be a genius, had invited his brother to Oxford to hear his protégé play part of a piano quartet he had just composed. Osbert also remarked on Walton’s head, which he described as ‘rather long, narrow, delicately shaped’ and with a ‘bird-like profile’. Before long, Walton was invited to London where he was to meet the third of the Sitwell siblings, Edith, who later noted that ‘his profile and mine…were so much alike in character and bone structure that many people who did not know us thought my two brothers, William, and I were three brothers and their sister.’

It was not long before Walton was ensconced, as a sort of composer-in-residence, in the attic of the Sitwell brothers’ London house at 2 Carlyle Square in Chelsea and it was there, on 24 January 1922, that Façade was to receive its first performance. Walton maintained that this ‘entertainment’ was Edith’s idea. According to Osbert it was the result of ‘certain technical experiments’ at which his sister had recently been working, ‘experiments in obtaining through the medium of words the rhythm of dance measures such as waltzes, polkas, foxtrots’. These exercises, Osbert explained, ‘were often experimental enquiries into the effect on rhythm, on speed, and on colour of the use of rhymes, assonances, dissonances, placed outwardly, at different places in the line, in most elaborate patterns.’ On hearing Edith read one of her poems, Sacheverell suggested that ‘it would be much better if you had music with it’ and it was soon agreed that Walton should compose the music to go not only with that poem but with several others as well. (Although reluctant at first, when told that if he would not write it they would offer the task to Constant Lambert, who was another young ‘genius’ of their acquaintance, Walton immediately agreed.)

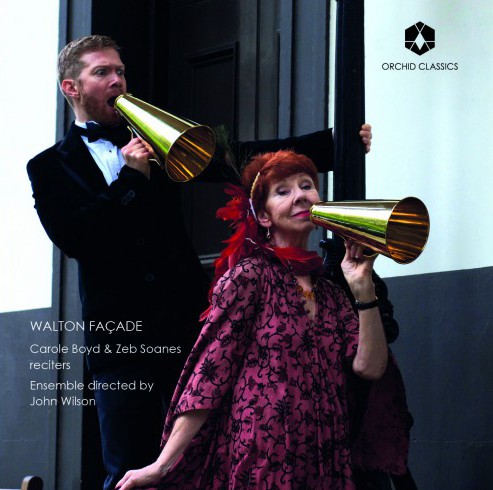

It is said that the title of these poems, and subsequently that of the musical composition they inspired, resulted from the judgement of a ‘bad artist, a painter with the side-whiskers of the period but with a name which, as it proved, has not attached itself to the epoch’ who claimed that Edith was ‘very clever, no doubt, but what is she but a façade?’ Although Walton had a reputation as a very slow worker, he claimed to have composed the first version of Façade in just three weeks. It was Osbert who came up with the idea that Edith should declaim her poems through a sengerphone (a kind of megaphone invented by the Swiss opera singer, George Senger, for the use of Fafner, the dragon in Wagner’s opera Siegfried) which would be positioned behind a curtain painted by Frank Dobson, along with the musicians who would therefore also be hidden. The intention was that those present should have the curtain to look at while listening to a human voice ‘speaking, not singing – but speaking at last on an equality with the music’. Thus they had, declared Osbert, ‘discovered an abstract method of presenting poetry to an audience’.

The first performance of Façade took place in the first-floor drawing room of 2 Carlyle Square before an audience of painters, musicians, poets and other worthies who were seated on ‘thin gold chairs’. For those who were likely to find the experience unsettling there was an ample supply afterwards of hot rum punch, described by Osbert as ‘an unusual but efficacious restorative’. One of the most enthusiastic listeners was Mrs Robert Mathias, an ardent patron of the arts who, as Helena Wertheimer, had been painted by John Singer Sargent in 1901. (It was in the same year that saw the first performance of Façade that the Wertheimer family presented this portrait to the Tate Gallery.) So keen was Mrs Mathias to hear the work again that she immediately requested that a repeat performance be given some two weeks later at her own home in Montague Square.

The first public performance of Façade did not take place until 12 June 1923 when a considerably amended version was heard at the Aeolian Hall in London’s New Bond Street with Edith as the reciter and Walton conducting the six instrumentalists. On that occasion the response of the audience was mostly hostile and Edith was warned not to come out from behind her curtain until everyone had left; ‘we had created a first-class scandal in literature and music’, claimed Osbert.

Two more public performances took place in 1926, this time at the New Chenil Galleries in Chelsea, and it was at this stage that Constant Lambert started to take over as the reciter. In a interview, many years later, Walton noted that it was over Façade that he had met Constant Lambert who was soon claiming that he could recite it better that anyone else could – and ‘of course he was right’ said Walton.

Façade is, indeed, dedicated to Lambert and in the printed score Walton acknowledges him as a collaborator in No.14 (Four in the Morning), the first eleven bars apparently having been written by him. The content of Walton’s ‘entertainment’ changed a good deal between 1923 and 1926 with items being dropped and new ones added from one performance to another. In its final form it ended up with twenty-one numbers set out in seven groups of three, a form which was suggested by Lambert as a parody of the Dreimal sieben Gedichte aus Albert Girauds ‘Pierrot lunaire’ (Three times Seven Poems from Albert Giraud’s ‘Pierrot lunaire’) which Arnold Schoenberg had set to even more controversial music than Walton’s in 1912 *. The first performance of this definitive version of Façade took place on 29 May 1942 at the Aeolian Hall with Lambert as speaker, Walton as conductor and the performers secreted behind a curtain designed by John Piper and painted by Alick Johnson.

* In his Pierrot lunaire, Schoenberg used a similar instrumentation to that chosen by Walton. Both require a cellist, a flautist who would also play the piccolo and a clarinettist to would also play the bass clarinet but, whereas Schoenberg had included a violinist doubling on viola and a pianist, Walton opted to complete his ensemble with a saxophonist, a trumpeter and a percussionist. Schoenberg also required his speaker to use the technique known in German as Sprechgesang, that is ‘speech-singing’ and invested more importance in the numerical aspect of his setting of these three times seven poems by giving the work the opus number 21 and requiring seven musicians, including the conductor, to perform it.

© Peter Avis, October 2016

Bibliography:

Laughter in the Next Room – Osbert Sitwell – Macmillan 1949

British Composers in Interview – Murray Schaffer – Faber & Faber 1963

Constant Lambert – Richard Shead – Simon Publications 1973

Beyond the Façade – Susana Walton – OUP 1988

Portrait of Walton – Michael Kennedy – OUP 1990

William Walton: A Catalogue – Stewart R. Craggs – OUP 1990

ALLUSIONS OF GRANDEUR – Understanding Façade

When Andrew Keener first spoke to me about making this recording, Dame Felicity Palmer cautioned, ‘Never underestimate Façade’, a work she has performed many times. It’s easy to think of Façade as nonsense poetry but in preparing the text for performance I was impressed how widely drawn Sitwell’s references are. When coupled with Walton’s music the sheer density and exoticism of her allusions transforms the voices into another percussive instrument as references fly past, particularly in the rapid-fire numbers such as Tarantella:

‘Trampling and sampling mazurkas1, cachacas2 and turkas3, Cracoviaks4 hid in the shade.’

(1Polish dance, 2Brazilian spirit distilled from sugar-cane, 3Turkish dance and 4Native of Kraków, Poland)

In this recording we wanted particularly to serve Sitwell’s poetry, given the often frenetic tempi set by Walton. I was thrilled when Carole Boyd agreed to take on the role of co-reciter; I had grown up hearing Carole’s voice on audio books and in later years as Lynda Snell in The Archers on BBC Radio 4 and I knew she would bring a Sitwellian quality to the project coupled with an actor’s approach to the text. Between us we went through the numbers, finding opportunities to share them wherever possible as new voices are introduced, which, in Sitwell’s somnambulistic imagination, isn’t always easy to discern. I think it makes this a very collaborative recitation.

Sitwell draws deeply on Greek and Roman mythology but real people also share her ethereal world with the nymphs and satyrs. Sir Joshua Jebb (En Famille) was the British Surveyor-General of prisons and helped to design Pentonville, Croesus (Tarantella) was a king, famous for his riches, hence the expression ‘as rich as Croesus’ and Baglioni and Grisi (Valse) were 19th Century Ballerinas – the original Sylphide and a noted Giselle. Valse is a veritable haberdashery of references to fabrics: tarlatine (muslin), balzarine (a blend of cotton and wool), barège (gauze), blond (silk lace) and her colours: retriever red, cassada green, bison black and elephantine grey read like a heritage paint-chart three decades before Farrow & Ball started their business.

Sitwell described her poetry in a letter to Robert Graves,

‘You say that my ‘ass-ear grass’ and ‘hairy sky’ etc, terrify you, and you want to know what makes me do it. It is rather difficult to explain. I think it is that I have always been in two lives, – if you can understand what I mean. It’s a queer somnambulistic floating back from my own perilous life to other people’s safe one … and waking up with a scream. Perhaps subconsciously I wish I could get on friendly terms with the safe kind of life I hate, and am never able to do it.’

Queer or not, I noted that her love of words has earned her immortality in the Oxford English Dictionary which adds this note to its definition of the word Ombrelles (parasols),

‘Only known in the work of Edith Sitwell.’

© Zeb Soanes, November 2016

A glossary of Sitwell’s references for Façade can be downloaded from www.zebsoanes.com

Carole Boyd trained at the Birmingham School of Speech & Drama, where she won the Carleton Hobbs Award –a six-month contract with the BBC Radio Drama Company. Extensive work in theatre led to her creation of Lynda Snell in The Archers. Voice-overs and audiobooks are a speciality including award-winning recordings of The God of Small Things, Suite Francaise and Middlemarch – but she feels most privileged to have won a Talkie for playing all the female characters in Postman Pat! TV appearances include Minder, Campion, Hetty Wainthrop and the evil Mrs. S. Melly in Bodger and Badger. She is delighted to be a part of this recording.

Zeb Soanes is a familiar voice across the BBC. He is a Radio 4 Newsreader for those who wake up to the Today programme and puts the nation to bed with The Shipping Forecast. He is a regular on Radio 4’s The News Quiz, reports for From Our Own Correspondent and has presented Radio 3’s Saturday Classics. On television his voice launched BBC Four, where he presented the BBC Proms. He was the Voice of God in the Britten Centenary production of Noye’s Fludde and concert work includes Peter and the Wolf, Little Red Riding Hood and The Snowman. Sunday Times readers voted him their favourite male voice on UK radio.

Born in Gateshead, John Wilson studied composition and conducting at the Royal College of Music, where he was taught by Joseph Horovitz and Neil Thomson. In 2011 he was made a Fellow of the College. A charismatic figure and communicator on the concert platform, known for his vivid interpretations of repertoire ranging from core classical through twentieth-century symphonic repertoire to reconstructions of Hollywood film scores, he has developed long-term affiliations with many major UK orchestras including the Philharmonia, City of Birmingham Symphony and the BBC Orchestras. In 2016/17 he became Associate Guest Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. Operatic work includes his debut at Glyndebourne Festival Opera with Madama Butterfly in Autumn 2016.