“I always knew I would have to climb this mountain, and during the enforced solitude of the last 18 months it became clear that the time was right.”

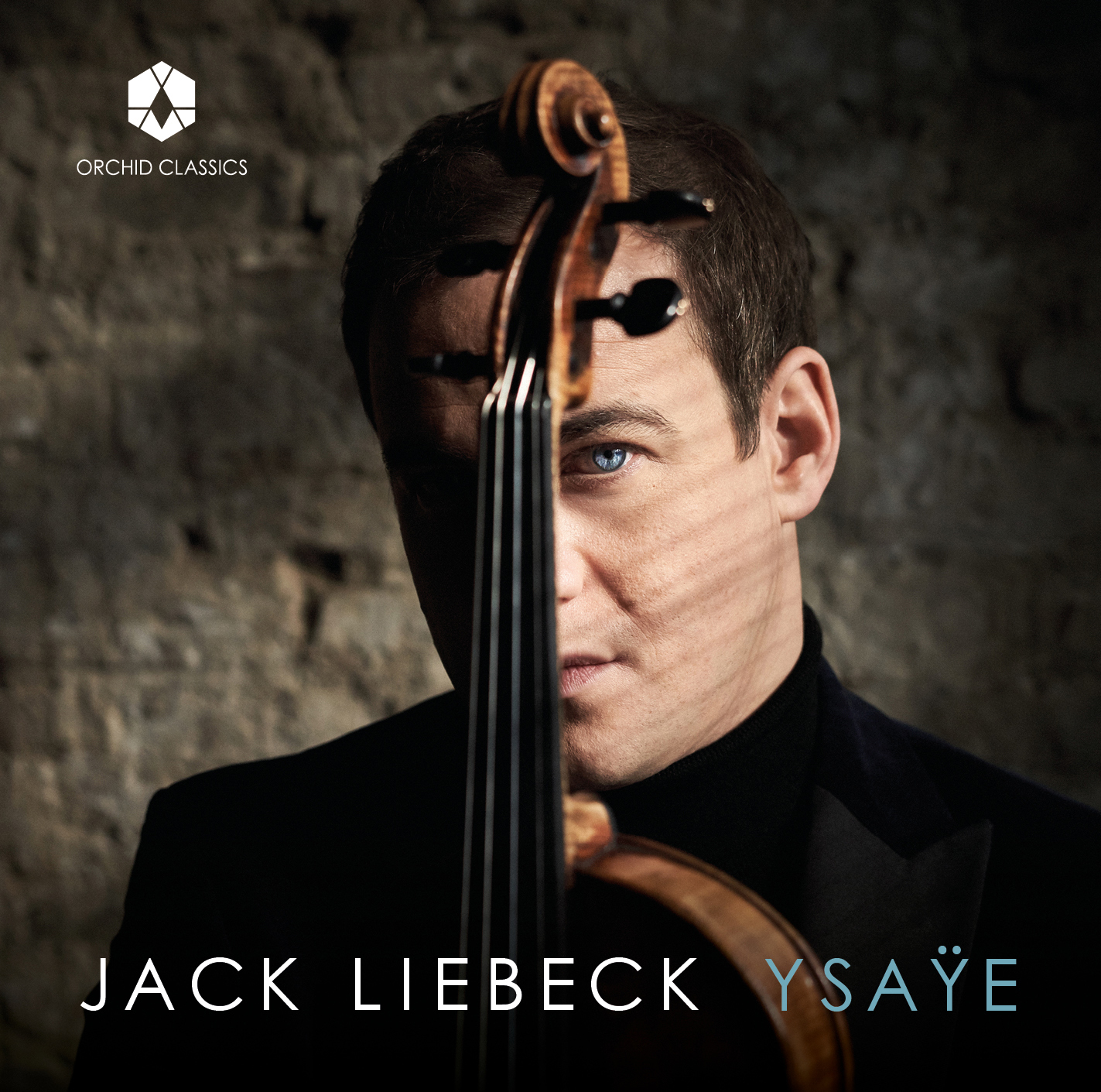

Following his acclaimed release of the Brahms and Schoenberg Violin Concertos, Jack Liebeck records one of the pinnacles of the violin repertoire, Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin.

SIX SONATAS FOR SOLO VIOLIN, OP.27

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Sonata No.1 in G minor

Dedicated to Joseph Szigeti

1. Grave: Lento assai

2. Fugato: Molto moderato

3. Allegretto poco scherzoso: Amabile

4. Finale con brio: Allegro fermo

Sonata No.2 in A minor

Dedicated to Jacques Thibaud

5. Obsession. Prélude: Poco vivace

6. Malinconia. Poco lento

7. Danse des ombres. Sarabande: Lento

8. Les furies. Allegro furioso

Sonata No.3 in D minor, “Ballade”

Dedicated to George Enescu

9. Lento molto sostenuto –

Allegro in tempo giusto e con bravura

10 Poème elégiaque in D minor for violin and piano*, Op.12 14.38

Dedicated to Gabriel Fauré

Sonata No.4 in E minor

Dedicated to Fritz Kreisler

11. Allemanda: Lento maestoso

12. Sarabande: Quasi lento

13. Finale: Presto ma non troppo

Sonata No.5 in G major

Dedicated to Matthieu Crickboom

14. L’Aurore. Lento assai

15. Danse rustique. Allegro giocoso molto moderato –

Moderato amabile – Tempo I – Poco più mosso

Sonata No.6 in E major

Dedicated to Manuel Quiroga

16. Allegro giusto non troppo vivo

Jack Liebeck, violin

Daniel Grimwood*, piano

“Mercurial” is the first word that comes to mind when trying to describe these epic sonatas for solo violin by Eugene Ysaÿe. They have been an obsession of mine since I first heard them early in my violinistic life. The European roots of my violin playing mean that I deeply feel the musical language of the sonatas, but it is also my love of this music which has moulded my playing, building it up in such a way that I could do justice to the music. I always knew that one day the time would come for me to make a recording of the complete set, having first recorded the “Ballade” (No.3) for my debut album in 2002. With this in mind, and following the enforced musical isolation of recent times, now seemed the perfect moment to climb this violinistic mountain, a set of works amongst the most virtuosic in the entire repertoire.

In my last recording I navigated the Schoenberg and Brahms Violin Concertos with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Andrew Gourlay; both works being rather more symphonic than their titles would suggest. Similarly, despite being solo violin sonatas, Ysaÿe flexes his harmonic and violinistic muscles to such a degree that the music almost competes in its musical power with those grand violin concertos. He creates a world that is Wagnerian in its swagger, juxtaposing this with incredibly delicate and fragile inner moments reminiscent of the finest Debussy. Ysaÿe’s style is best described as monumental, with gothic themes, drama, and poignancy. I have endeavoured to bring out this perspective and range to the maximum as I feel that it is in this contrast where the power of the music is to be found.

As we approach the centenary of their publication in 2024, it feels a suitable moment to reflect that these Sonatas are the pinnacle of harmonic and technical challenge for the violin. Having been written by a great virtuoso (as musical gifts for the violinist contemporaries he most admired), they are so precisely tailored to the strength and sonority of the instrument that they fit a violinist’s hand like a glove – a gift for us all. The Sonatas exploit what I most value in violin playing, beautiful technical and physical motion that in turn creates music of equal beauty.

Jack Liebeck

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931) was born into a family of violinists in Liège and soon showed a prodigious aptitude for the instrument. His formative years were cosmopolitan and the young Ysaÿe absorbed influences from a range of sources, sowing the seeds for his philosophy that “real art should be international.” At the tender age of seven he began his studies at the Liège Conservatoire, and at 16 he travelled to Brussels, where he studied with fellow Belgian Henri Vieuxtemps and Polish violinist Henryk Wieniawski. According to the Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, Ysaÿe considered Wieniawski to be “the greatest of his contemporaries”. Then in Paris, Ysaÿe met the Russian pianist-composer Anton Rubinstein, who had a profound impact on his tastes, after which he headed for Berlin, becoming a founder member of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Ysaÿe returned to Paris in 1893. He joined the so-called “bande à Franck”, a group of musicians orbiting another Belgian composer, César Franck. Ysaÿe’s exceptional skills were soon recognised and a breathtaking line-up of works was composed for, or dedicated to him, including Franck’s Violin Sonata, Chausson’s Poème – inspired by Ysaÿe’s Poème élégiaque – and the string quartets of Saint-Saëns, Debussy, and Vincent d’Indy.

At his best, Ysaÿe was considered the finest violinist of his generation. Health concerns intervened, however, and the onset of diabetes limited his capacity to perform. And so it was that Ysaÿe became increasingly devoted to composition, channelling the creativity he was no longer able to pour into his own performances into pieces written for others. It was Szigeti who prompted Ysaÿe’s most significant contribution to the repertoire. In July 1923, Ysaÿe attended a performance given by Szigeti of J.S. Bach’s Sonata for solo violin in G minor, BWV 1001, the first of his set of six solo violin sonatas and partitas, Sei Solo – a violino senza Basso accompagnato, BWV 1001-1006. Ysaÿe was so inspired that he produced his own Six Sonates pour violon seul in just 24 hours.

Luciano Berio would argue that in Bach the “violin techniques of the past, present and future coexist”, and Ysaÿe’s Sonatas, in which Bach’s influence is palpable alongside features more typical of the 20th century, bear this out. The works also communicate something of the spirit of each of their dedicatees, who represent a range of different nationalities. The Sonata No.1 is typical of this mixture; dedicated to Szigeti, the work blends folk-like, modal Hungarian traits with neoclassical nods to Bach such as the opening Grave and the second-movement Fugato.

Subtitled ‘Obsession’, the Sonata No.2 is dedicated to the French violinist Jacques Thibaud, who regularly toured with the Romanian violinist-composer George Enescu, dedicatee of the Sonata No.3, and who taught the Sixth Sonata’s dedicatee, Spanish violinist Manuel Quiroga. Thibaud invariably – perhaps obsessively – warmed up by playing the ‘Prelude’ to Bach’s Partita No.3 in E (BWV 1006). Ysaÿe includes quotations from this piece throughout the Sonata, alongside imposing allusions to the Dies irae (“day of wrath”) plainchant from the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. The juxtaposition of these contrasting materials creates a sort of musical collage, reflecting wider trends in early 20th-century art such as the paintings of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso.

Ysaÿe includes vivid movement titles in the Sonata No.2. The first movement’s ‘Obsession’ focusses on the tussle between Bach and the plainchant; ‘Malinconia’ (‘Melancholy’) conveys desolate loneliness. The ‘Danse des ombres’ (‘Dance of Shadows’) is a Sarabande, a triple-meter dance again harking back to Baroque precedents, but with the addition of vibrant pizzicato, folk-like, rustic pedal drones and multiple-stopping. The ‘shadows’ appear in the form of variations. In ‘Les furies’, scordatura (when a string is retuned) creates astringent clashes reminiscent of the Danse macabre by Saint- Saëns, or of Paganini’s devilish displays. Ysaÿe had used this technique in many of his youthful works; the unusual sonority and extra challenges inherent in playing the retuned violin add an extra frisson of daring and skill to a virtuoso performance.

Ysaÿe’s Violin Sonata No.3, Ballade, was written for Enescu and is at once concise in length and wide-ranging in scope. Yehudi Menuhin argued that Enescu embodied the breadth of Western violin music – a breadth embraced by Ysaÿe in these sonatas: “Enescu’s mind dealt in centuries… wide measures of time and space … his memory held the collected works of all the great composers from Bach to Bartók.” Over the course of a single movement, Ysaÿe’s violin writing becomes increasingly animated as it leads into a complex, technically demanding Allegro. Ysaÿe’s student, Josef Gingold, suggested that the Third Sonata is the closest of all to Ysaÿe’s own style of playing.

Dedicated to Fauré, the Poème élégiaque, Op.12, was composed rather earlier in Ysaÿe’s career, in 1892-93. The piece is a step away from his youthful showpieces, but still includes the virtuosic staple of scordatura, in this case with the G string tuned to an F to create a dark, woody timbre. Originally for violin and piano, Ysaÿe went on to arrange the piece for violin and orchestra. Its intense, intoxicating romanticism fired the imagination of Ernest Chausson, who wrote his Poème in 1896 for and with Ysaÿe, even referring to his work as “mon–ton poème” (“my–your poem”).

Of all his Six Sonatas, the Sonata No.4 was Ysaÿe’s favourite. It is dedicated to the Austrian violinist-composer Fritz Kreisler, who was not known as an interpreter of Baroque music, but who was skilled at writing pastiche. Ysaÿe acknowledged this in the neoclassical opening movements, and during the final Presto ma non troppo, with its allusions to Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro in the style of Pugnani. The first two movements recall those of a Baroque suite: an Allemanda (a dignified German dance), and a Sarabanda (a Spanish dance in triple time). The final Presto is in a more fluid, modernist style, but is connected to the Sarabanda by an insistent motif that permeates both movements, including the joyous final coda.

The Sonata No.5 is dedicated to Ysaÿe’s most devoted disciple and a member of the Ysaÿe Quartet, the Belgian violinist Mathieu Crickboom. An ethereal opening movement, ‘L’aurore’, evokes the dawn, followed by a ‘Danse rustique’ with folk-like open harmonies. The use of whole-tones and quarter-tones, as well as ‘contrapuntal’ devices such as sustained notes interrupted by pizzicato interjections, are remarkably forward-looking, and there are parallels to be drawn between these innovations and those in Bartók’s Violin Sonatas, which date from 1921 and 1922 – just a year or so earlier than Ysaÿe’s set.

Manuel Quiroga, the dedicatee of the Sonata No.6, never got a chance to play the work owing to an injury that cut short his promising career. But he is immortalised in its music: a colourful, single-movement habanera conjuring up Quiroga’s native Spain.

Ysaÿe’s Six Solo Sonatas are, according to David Oistrakh, characterised “by the truest inspiration and originality. At the same time they open up new horizons in the history of violin virtuosity: in them Ysaÿe stands out as the greatest innovator after Paganini.” As these works attest, Ysaÿe, like Paganini, relished technical virtuosity – but he also regarded it as a vehicle for emotional expression rather than as an end in itself. Ysaÿe declared that: “… at the present day the tools of violin mastery, of expression, technique, mechanism, are far more necessary than in days gone by. In fact they are indispensable, if the spirit is to express itself without restraint.”

© Joanna Wyld, 2021

Following his acclaimed release of the Brahms and Schoenberg Violin Concertos, Jack Liebeck returns to Orchid Classics with Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, as well as the lyrical Poème élégiaque for violin and piano, for which Liebeck is joined by Daniel Grimwood.

Ysaÿe was hailed as the greatest violinist of his day until illness cut short his career as a soloist, prompting him to channel his energies into writing these sonatas dedicated to six of his most outstanding contemporaries, including George Enescu and Fritz Kreisler. Jack Liebeck has been playing Ysaÿe’s music since he was a teen and has always felt a natural affinity with this repertoire: “I’ve always felt it was in my blood – its romantic richness felt right for my playing, my voice”. Recording Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas was a case of when, rather than if: “I always knew I would have to climb this mountain, and during the enforced solitude of the last 18 months it became clear that the time was right.”

Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas were inspired by hearing Joseph Szigeti play J.S. Bach’s Sonata for solo violin in G minor, BWV 1001, and each sonata was composed with a specific colleague in mind. For Liebeck, this is crucial; as he explains, whereas a composer such as Paganini was writing for himself, “Ysaÿe was a violinist writing for his admired colleagues” so “his writing always feels comfortable. Despite its technical demands, the writing is so clever because it is entirely idiomatic. It is tailored to the violinist’s hands like a piece of clothing – it fits beautifully.”

Bach’s influence is palpable throughout the set, alongside folk idioms that reflect the nationality of each dedicatee, and more characteristic 20th-century elements. Liebeck observes that the sonatas become more adventurous and individual as they go along. He is also particularly struck by their rich textures: “The violin is by nature a sociable instrument in that it is essentially melodic, but Ysaÿe somehow manages to create incredibly interesting harmonies and a sense of harmonic direction in these works. The soloist has to channel multiple personalities. It is difficult to believe that this music is being produced by a single instrument”.

Jack Liebeck’s previous Orchid Classics release was a recording of the Brahms and Schoenberg Violin Concertos, for which BBC Music Magazine praised his “astonishing command, allowing the music’s expression to speak with a real degree of freedom, even fantasy…” At first glance, solo violin music may seem a much more intimate undertaking, but Ysaÿe achieves incredible richness in this context, as Liebeck argues: “Ysaÿe manages to create the same monumental, Wagnerian scale, full of Gothic drama – a sense of conquering the world via the solo violin.”

Even so, Liebeck acknowledges that the Six Solo Sonatas may not have been intended to be heard back-to-back, so he made the decision to break up the group with a refreshing interlude in the form of Ysaÿe’s delicious Poème élégiaque for violin and piano, for which he collaborated with friend Daniel Grimwood, praised by The Telegraph for playing that is “Stimulating and revelatory in equal measure”.

Jack Liebeck’s recent engagements have included LIVE From London Summer featuring Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time with Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Katya Apekisheva and Julian Bliss alongside a new arrangement for voices and violin of The Lark Ascending with VOCES8. Upcoming engagements include Bournemouth Symphony, Philharmonia, Uppsala and Queensland Symphony. He is also a member of the Salieca Piano Trio.

From 2022, Jack Liebeck will be the Artistic Director of the Australian Festival of Chamber Music (AFCM). He is also the artistic director of his own festivals Oxford May Music and Alpine Classic in Grindelwald, Switzerland. As the first Émile Sauret Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music he works as an ambassador helping to recruit future talent both at home and internationally. He plays the ‘Ex-Wilhelmj’ J.B. Guadagnini violin dated 1785 and is generously loaned a Joseph Henry bow by Kathron Sturrock in the memory of her late husband Professor David Bennett.

For Jack Liebeck’s official bio and publicity pictures please visit Percius Management

For Jack Liebeck’s official bio and publicity pictures please visit Percius Management

Jack Liebeck

Violin

In the 25 years since his debut with the Hallé, Jack Liebeck has worked with some of the world’s leading conductors including Andrew Litton, Leonard Slatkin, Karl-Heinz Steffens, Sir Mark Elder, Sakari Oramo, Vasily Petrenko, Sir Neville Marriner, Brett Dean, Daniel Harding, Jukka Pekka Saraste, David Robertson, Jakub Hrůša and major orchestras across the globe including Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Swedish Radio, Oslo Philharmonic, Belgian National, MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony, Moscow State Symphony, Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia, St Louis Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony and most of the UK orchestras.

Jack’s fascination with all things scientific culminated in the founding of his own festival in 2008 to combine Music, Science and Art, Oxford May Music. He has collaborated with physicist Professor Brian Cox in several unique symphonic science programmes which have included the world premieres of two violin concertos written especially for Jack, Voyager Concerto by Dario Marianelli commissioned by the Queensland Symphony and Swedish Radio orchestras, and A Brief History of Time by Paul Dean, commissioned by Melbourne Symphony.

Jack is the Artistic Director of the Australian Festival of Chamber Music from 2022, Émile Sauret Professor of Violin at the Royal Academy of Music and a member of Salieca Piano Trio. Also a professional photographer, he enjoys collaborating across many mediums and can be heard in the film soundtracks of The Theory of Everything, Jane Eyre and Anna Karenina.

Jack plays the ‘Ex-Wilhelmj’ J.B. Guadagnini violin dated 1785, and the ‘Professor David Bennett’ Joseph Henry bow.

Daniel Grimwood

Piano

With repertoire ranging from Elizabethan Virginal music to the works of living composers, Daniel Grimwood enjoys both a solo and chamber career which has taken him across the globe. His musical interest started as a 3-year-old playing next door’s piano, and from the age of 7 he was performing in front of audiences.

Although primarily a pianist, he is frequently found performing on harpsichord, organ, viola or composing at his desk. Grimwood is a passionate exponent of the early piano and has given a recital of Chopin’s Etudes on the composer’s own Pleyel piano.

His most recent CD releases include a disc of works by William Alwyn and Doreen Carwithen, “Daniel Grimwood dispatches with aplomb” (Jeremy Nicholls, Gramophone), and works by Adolph Von Henselt who’s “virtuosic compositions have found a modern champion in British pianist Daniel Grimwood. Titanic variations, lilting waltzes, thundering impromptus and reflective nocturnes send the senses reeling in a blizzard of dazzling pianism, Grimwood admirably demonstrating why Henselt, who settled in St Petersburg, was considered the father of Russian pianism” (Stephen Pritchard, The Guardian).

As editor, Grimwood is currently preparing editions of Adolph von Henselt’s Piano Concerto and complete Etudes for Edition Peters.

Daniel Grimwood regularly performs on live broadcasts on BBC Radio 3 and has been featured in BBC Four’s TV documentary series Revolution and Romance.

Click the button above to download all album assets.