Artist Led, Creatively Driven

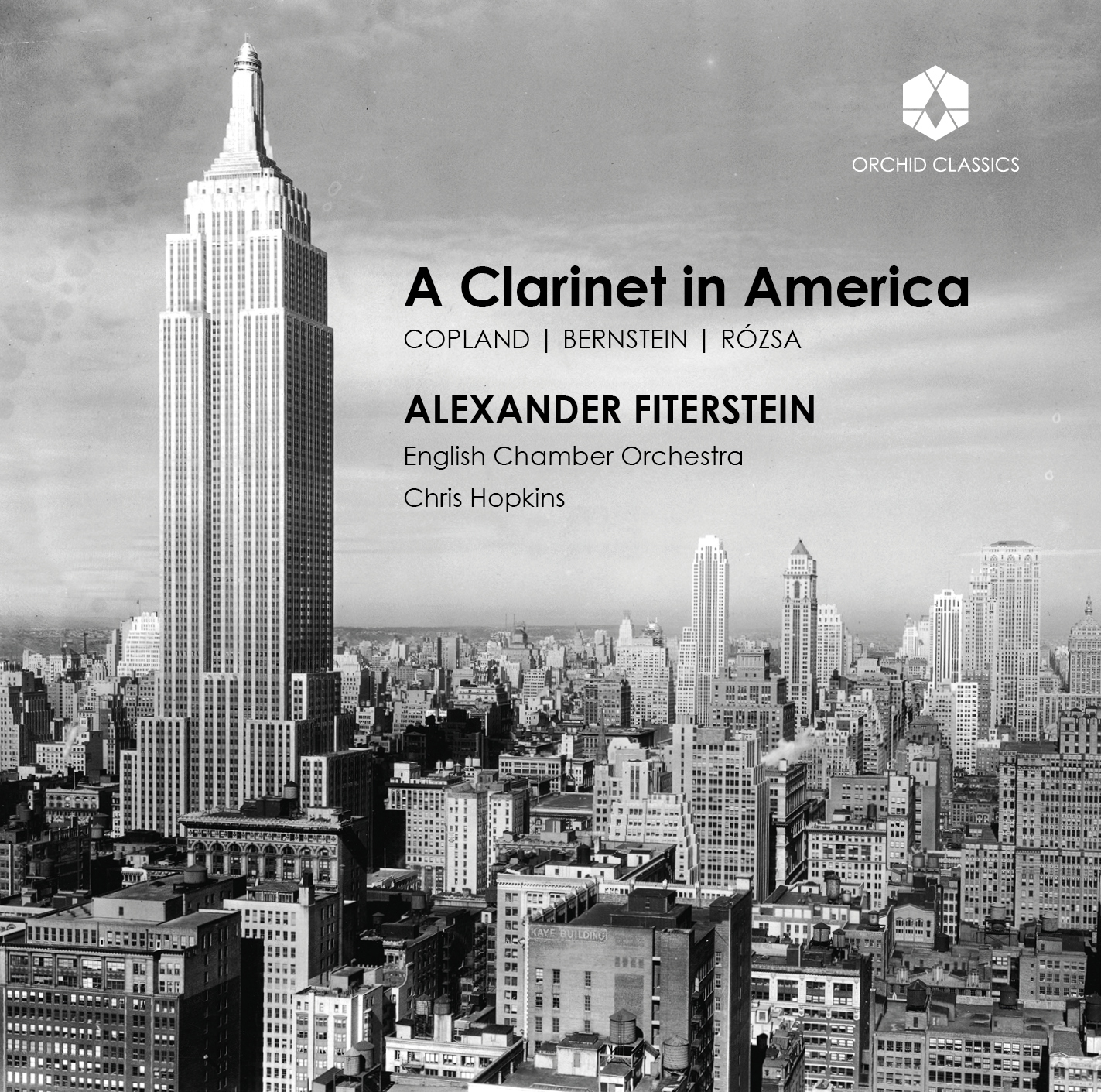

A Clarinet in America

Alexander Fiterstein

English Chamber Orchestra

Chris Hopkins

Release Date: Feb 12th 2021

ORC100155

A CLARINET IN AMERICA

Aaron Copland (1900 – 1990)

Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra

(with harp and piano)

1 Slowly and expressively 8.12

2 Rather fast 7.55

Leonard Bernstein (1918 – 1990)

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano

3 I Grazioso 3.45

4 II Andantino-Vivace leggiero 6.58

Miklós Rózsa (1907 – 1995)

Sonatina for Clarinet Solo Op.27

5 Tema con variazioni 6.35

6 Vivo e giocoso 3.39

Aaron Copland

Sonata for Clarinet and Piano

7 Andante semplice 7.31

8 Lento 5.06

9 Allegretto giusto 7.00

Total timing 56.44

Alexander Fiterstein, clarinet

English Chamber Orchestra

Chris Hopkins, conductor / piano

On 14 November 1937, the nineteen-year-old Leonard Bernstein found himself sitting in the front row of the balcony at the Guild Theater in New York next to someone he described as ‘an odd-looking man in his thirties’ with ‘a pair of glasses resting on his great hooked nose and a mouth filled with teeth’. When he was introduced to this neighbour and learnt that he was seated beside Aaron Copland, he was astonished as he had imagined that this composer he greatly admired would look like ‘a cross between Walt Whitman and an Old Testament prophet’. As it happened to be Copland’s birthday – his thirty-seventh – he invited Bernstein to join him and several of his friends at a party in his studio. Bernstein had recently learnt to play Copland’s Piano Variations and would play them often although, as he had to admit, his performances tended to empty the room. On this occasion, however, when Copland dared him to play the piece, nobody left.

According to Bernstein, Copland was the most sensational human being he had ever come across and later claimed that the closest he ever came to studying composition with anyone was by showing everything he wrote to the older man. A close friendship developed between them and they would often play piano reductions of Copland’s works together. As it turned out, the first time that Bernstein’s name was to appear in print on a musical score was in 1941 when his own piano transcription of Copland’s El Salón México was published.

Bernstein graduated from Harvard University in 1939, going on to study conducting with Fritz Reiner at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. In 1940 he enrolled at the Berkshire Music Center, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home at Tanglewood in northwestern Massachusetts, in order to continue his studies with its conductor Serge Koussevitzky. Copland was also on the teaching staff at Tanglewood, as was the distinguished German composer Paul Hindemith.

Following the 1941 Tanglewood Festival, Bernstein went for a holiday in Key West, Florida and there, influenced by the Cuban music he heard on Radio Havana, settled down to composition, one of the resulting pieces being a sonata for clarinet. Two years earlier, depressed and with no work, he had spent his last four dollars on a clarinet he had seen in a pawn shop. This, he claimed, comforted him for a while. He completed the Sonata the following year in Boston and its first performance was given there on 21 April 1942 at the Institute of Modern Art by the composer and the clarinettist, David Glazer, with whom he had shared a room at Tanglewood.

For that year’s festival, Bernstein had been appointed Koussevitzky’s assistant. In the orchestra was the twenty-two-year-old clarinettist David Oppenheim and, before long, Bernstein was telling Copland, now his mentor and confidant, of an idyllic hitchhiking holiday he and Oppenheim were enjoying in New England. On 21 February 1943, the two of them gave the first broadcast performance of the Clarinet Sonata and three weeks later, the first public perfomance in New York. Not surprisingly, Bernstein dedicated the piece to his new friend.

Later in 1943 – on 14 November, Aaron Copland’s forty-third birthday – Bernstein found himself conducting the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at an afternoon concert in the Carnegie Hall. The conductor should have been Bruno Walter but he had been taken ill at the last moment and the orchestra’s chief conductor, Artur Rodzinski, was on leave. With no time for rehearsal – just a few words with Walter – Bernstein, by then Rodzinski’s assistant, had to take charge. On the programme were works by Schumann, Richard Strauss, Wagner and Miklós Rózsa. Although he had never before conducted Rózsa’s Theme, variations and finale, Bernstein’s performance of it ‘brought the house down’. Thus was born Bernstein’s international career as a conductor.

Miklós Rózsa was born in Budapest in April 1907 and started playing the violin at the age of five. In 1925 he moved to Leipzig to study both chemistry and music, but soon decided to concentrate on the latter. He was to live in Paris during the early 1930s before moving to London where fellow Hungarian Alexander Korda invited him to write the music for some of the films he was about to produce. This work later took him to Hollywood where he continued to write film scores, three of which – Ben-Hur, A Double Life and Spellbound – were to win him Academy Awards. As well as composing music for the cinema which was admired by Aaron Copland amongst many others, Rózsa taught composition at the University of Southern California at Santa Barbara from 1945 until 1965 and took American citizenship in 1946. He died in Los Angeles on 27 July 1995 at the age of eighty-eight.

Rózsa composed two works for solo clarinet – the Sonatina, Op.27 and the Sonata, Op.41. The later work was given its first performance by Gervase de Peyer in 1987 but there seems to be confusion over the origins of Op.27, with some sources giving 1951 as the date of composition and others 1957; indeed, in Christopher Palmer’s monograph about the composer, both dates are given, the first in the work list and the second in the text. In his autobiography – Double Life – Rózsa mentions the Sonatina only in passing but, in the list of his compositions it appears, along with a Suite for Orchestra from his latest film Quo Vadis, in the year 1951. There is no reference to a first performance but it seems that the first recording of it was made by Charles MacLeod who was Principal Clarinet with the Santa Barbara Symphony Orchestra. Rózsa dedicated the Sonatina to fellow film composer, Bronislau Kaper. Born in Warsaw in 1902, Kaper composed the music for many films notably Mutiny on the Bounty, a commission which had first been offered by MGM to Rózsa who was too busy at the time with the score of El Cid for another film company.

On 23 October 1943, a US Army aircraft, piloted by 1st Lieutenant Harry Hickenlooper Dunham, crashed on its way to New Guinea. Born in Cincinnati in 1910, Dunham was a film cinematographer in civilian life and a close friend of Aaron Copland. At that time, Copland was composing a Violin Sonata which he subsequently dedicated to Dunham’s memory. The Sonata was given its first performance on 17 January 1944 at New York’s Town Hall by the composer and the violinist Ruth Posselt, wife of Richard Burgin who was another member of the Tanglewood teaching staff.

It was in 1978, at the suggestion of Timothy Paradise, who was then Principal Clarinet with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, that Copland transcribed his Violin Sonata for clarinet and piano, transposing it down a major third to make good use of the clarinet’s lower register. He was assisted in this task by Michael Webster who was to give this version its first performance with the pianist Barry Snyder on 10 March 1986 at the Merkin Concert Hall in New York City.

Copland began to compose his Clarinet Concerto in 1947 in Rio de Janeiro during a goodwill tour of South America arranged by the US State Department. It had been commissioned the previous year by the American jazz clarinettist and ‘King of Swing’, Benny Goodman (1909-1986) who was also a fine performer in the concert hall. Some ten years earlier, Goodman had commissioned Béla Bartók to compose a work for him – Contrasts for clarinet, violin and piano – and he was later to give the first performances of works by several other composers including Francis Poulenc (his Clarinet Sonata with Leonard Bernstein as pianist) and Bernstein’s own Prelude, Fugue and Riffs.

Copland continued work on his Clarinet Concerto at Tanglewood in the summer of 1948, completing it at his home in Sneden’s Landing that October. Goodman, as he later told an interviewer, had ‘made no demands on what Copland should write’ but at their first read-through of the completed work – in the presence of David Oppenheim – Goodman did ask for a few changes to be made.

The Concerto was heard for the first time on 6 November 1950 during an NBC radio broadcast with Goodman as soloist, the NBC Symphony Orchestra being conducted by Fritz Reiner. The first public concert performance took place at New York’s Carnegie Hall on 28 November when the Philadelphia Orchestra was conducted by Eugene Ormandy and Ralph McLane, the Orchestra’s Principal Clarinet, was the soloist. Goodman and Copland were to record the work twice, first in 1950 and then in 1963. (There had been talk of Bernstein and Oppenheim recording the Concerto at about that time but in the event Bernstein did not record it until 1989 and then with Stanley Drucker.)

In 1951, the Concerto was used for The Pied Piper, a ballet choreographed by Jerome Robbins (who was later to work with Bernstein on West Side Story), the piper being the clarinet and not the Pied Piper of Hamelin, the subject of Robert Browning’s famous poem.

© 2020 Peter Avis

Alexander Fiterstein is considered one of today’s most exceptional clarinettists. Fiterstein has performed in recital, with distinguished orchestras, and with chamber music ensembles throughout the world. He won first prize at the Carl Nielsen International Clarinet Competition and received the prestigious Avery Fisher Career Grant Award. The Washington Post has described his playing as “dazzling in its spectrum of colors, agility, and range. Every sound he makes is finely measured without inhibiting expressiveness” and The New York Times described him as “a clarinettist with a warm tone and powerful technique.”

As soloist he has appeared with the Czech, Israel, Vienna, and St. Paul Chamber Orchestras, Belgrade Philharmonic, Danish National Radio Symphony, Tokyo Philharmonic, China National Symphony Orchestra, KBS Orchestra of South Korea, Jerusalem Symphony, Orchestra of St. Luke’s at Lincoln Center, Kansas City Symphony, and the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela. He has performed in recital on the Music at the Supreme Court Series, the Celebrity Series in Boston, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, the Kennedy Center, the Louvre in Paris, Suntory Hall in Tokyo, Tel Aviv Museum, and NYC’s 92d Street Y.

A dedicated performer of chamber music, Fiterstein frequently collaborates with distinguished artists and ensembles and regularly performs with the prestigious Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Among the highly regarded artists he has performed with are Daniel Barenboim, Yefim Bronfman, Mitsuko Uchida, Richard Goode, Emanuel Ax, Marc-Andre Hamelin, Pinchas Zukerman, and Steven Isserlis. He spent several summers at the Marlboro Music Festival and appeared at the Caramoor, Moab, Music@Menlo, Montreal, Toronto, Jerusalem, and Storioni Chamber Music Festivals.

Fiterstein has a prolific recording career and had pieces written for him by Samuel Adler, Mason Bates and Paul Schoenfield. He was born in Belarus and immigrated to Israel at the age of two with his family. A Juilliard graduate, he won first prize at the Young Concert Artists International Auditions and received grants from the America-Israel Cultural Foundation. He is currently Associate Professor of Clarinet and Chair of Woodwinds at the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University. Fiterstein is a Buffet Crampon and Vandoren Performing Artist.

Equally at home on the concert stage as in the pit, conductor and pianist Chris Hopkins is engaged on a wide range of projects across many disciplines. Recently appointed principal conductor of the English Sinfonia, he is also a frequent face at the London Coliseum, following the success of his ENO conducting debut in 2017. He has since returned to conduct The Magic Flute, Iolanthe and the most recent revival of the legendary production of The Mikado (‘faultlessly conducted by the excellent Chris Hopkins’ London Theatre Reviews). Previously he has worked at the Royal Opera House, Glyndebourne Opera, Opera de Paris, Grange Festival Opera, English Chamber Orchestra, Royal Ballet Sinfonia, Crash Ensemble, WNO, NI Opera, HGO, Opera Holland Park, Wide Open Opera, Garsington Opera, Grange Park Opera, Opera Danube, London Mozart Players, and appeared at many festivals including Aldeburgh, Presteigne, and Latitude. He has performed throughout the UK, in the US, Asia and extensively in Europe as well as live and recorded appearances on BBC 1, Classic FM and BBC Radio 2, 3 and 4. Chris was honoured in 2013 to be made an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music.

The English Chamber Orchestra is the most recorded chamber orchestra in the world, its discography containing 860 recordings of over 1,500 works by more than 400 composers.

The ECO has also performed in more countries than any other orchestra, and played with many of the world’s greatest musicians. The American radio network CPRN has selected ECO as one of the world’s greatest ‘living’ orchestras. The illustrious history of the orchestra features many major musical figures. Benjamin Britten was the orchestra’s first Patron and a significant musical influence.

The ECO’s long relationship with Daniel Barenboim led to an acclaimed complete cycle of Mozart piano concertos as live performances and recordings, followed later by two further recordings of the complete cycle, with Murray Perahia and Mitsuko Uchida.

Recent tours have included the USA, Bermuda, China, Finland, France, Greece, Slovenia and Austria (culminating in a concert at Vienna’s Musikverein) as well as concerts across the UK and at London’s Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Kings Place and Cadogan Hall.

The Orchestra has been chosen to record many successful film soundtracks including Dario Marianelli’s prizewinning scores for Atonement and Pride and Prejudice, and several James Bond soundtracks, and has taken part in a variety of other film and television projects.

The ECO is proud of its outreach programme, Close Encounters, which is run by the musicians in the orchestra and takes music into many settings within communities and schools around the UK and abroad.