Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Beethoven/Liszt “Pastoral” Symphony

Ashley Wass, fortepiano

Release Date: October 2012

ORC100024

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony No.6 in F, Op.68 “Pastoral”

Piano Transcription: Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Erwachen heiterer Empfindungen bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande (The awakening of cheerful feeling on arriving in the country)

Allegro ma non troppo

Szene am Bach (Scene at the brook)

Andante molto moto

Lustiges Zusammensein der Landleute (Merry meeting of country folk)

Allegro

Gewitter. Sturm (Thunderstorm. Tempest)

Allegro

Hirtengesang. Frohe und dankbare Gefühle nach dem Sturm (Song of the Shepherds. Glad and thankful feelings after the storm)

Allegretto

Ashley Wass (fortepiano)

FOREWORD BY JOOLS HOLLAND

I first encountered the Pastoral Symphony when I was eight, around the same time I started to learn the piano. My method of study was based largely on copying the people around me, and the chaos of the universe had become ordered at the moment I heard my uncle playing boogie woogie. I discovered I could recreate his music by ear and naturally assumed – rather optimistically – the same approach would work on the Pastoral. I approached a kindly teacher at my school and asked if they could play it on the piano so that I, in my own naïve fashion, could copy them. At the time I was told a transcription probably did exist, but the teacher in question was not familiar with it. Years passed and this episode was largely forgotten, but at the back of my mind I still desperately wanted to hear the symphony on piano. When news came through there was to be a performance at Restoration House, I was anxious to attend: this was something I’d been waiting most of my life to experience.

Restoration House is a wonderful venue with a very special atmosphere, great acoustics and a unique fortepiano. The owners, Robert and Jonathan, arranged a concert of Liszt’s transcription of the Pastoral to be performed by the extraordinarily talented Ashley Wass. I was curious and unsure what to expect, but it turned out to be one of the best live performances I’ve ever heard. Composers often use pianos as their sketchpad and hearing Ashley play the symphony on the piano made me feel as if I was peering at Beethoven’s notes, discovering for the first time his spontaneous ideas and brilliant thoughts. It reinvented the piece and made me realise, once again, what an incredible work it is. And Ashley’s combination of attack and sensitivity brought another dimension to what is already something of great beauty.

I was recently asked what good music is. I had to think carefully before answering – after all, it’s very subjective and we all have differing tastes – but I eventually concluded that, for me, good music is defined by the desire to hear it again and again. That is certainly the case with this recording.

BEETHOVEN: SYMPHONY NO.6 “PASTORAL”

Premiered in December 1808 as part of a typically under-rehearsed concert marathon, Beethoven’s Symphony No.6 “Pastoral” disguises its complexities behind a veil of simplicity, demonstrating Beethoven’s extraordinary ability to construct large-scale compositions on miniscule motifs, and offering confirmation – were it needed – of his status as a master melodist.

Although described by Beethoven himself as “more the expression of feeling than painting”, there can be few works of any genre that so vividly portray their subject. From the birdsong which closes the second movement (so carefully notated and identified in the score) to the violent storm (even Liszt’s own “Orage” from the first book of Années de Pèlerinage has to concede ground in ferocity) and the heart-rending reappearance of sunshine and prayer in the Finale, the composer’s evident empathy for the natural world is conveyed in a manner both literal and spiritual.

It was during the summer of 1837, while staying at George Sand’s Nohant home, that Liszt began work on his solo piano transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies. Initially published in 1840, they underwent further revision before reappearing in their new form under the auspices of Breitkopf & Härtel in 1865.

Liszt’s admiration for Beethoven was evident throughout his life and career. Amongst his most treasured possessions were Beethoven’s death mask and Broadwood piano, and, in his later years, he recalled receiving praise following a childhood performance for the great master as “the proudest moment in my life – the inauguration to my life as artist.” Beethoven’s works were regularly included in his recitals and his transcription of the “Pastoral” appeared in his programmes almost immediately upon completion: concert flyers for his 1840 tour of England indicate he performed at least the Scherzo and Finale.

The instrument on which the “Pastoral” was recorded for this CD is a Girikowsky fortepiano, hailing from Moravia and dating from the mid-1820s. Although several concessions and revisions had to be made for a keyboard compass more limited than the Erards on which Liszt usually worked and performed in the 1830s and 40s, the warm timbre and distinctive sounding pedals recall closely the colour and vibrancy of the original orchestral score.

The name of Beethoven is sacred in art. His symphonies are at present universally acknowledged to be masterpieces; whoever seriously wishes to extend his knowledge or to produce new works can never devote too much reflection and study upon them. For this reason every way or manner of making them accessible and popular has a certain merit, nor are the rather numerous arrangements published so far without relative merit, though, for the most part, they seem to be of but little intrinsic value for deeper research. The poorest lithograph, the most faulty translation always gives an idea, indefinite though it be, of the genius of Michel Angelo, of Shakespeare, in the most incomplete piano-arrangement we recognize here and there the perhaps half-effaced traces of the master’s inspiration. By the development in technique and mechanism which the piano has gained of late, it is possible now to attain more and better results than have been attained so far. With the immense development of its harmonic power the piano seeks to appropriate more and more all orchestral compositions. In the compass of its seven octaves it can, with but a few exceptions, reproduce all traits, all combinations, all figurations of the most learned, of the deepest tone-creations, and leaves to the orchestra no other advantages, than those of the variety of tone-colours and massive effects – immense advantages, to be sure.

Such has been my aim in the work I have undertaken and now lay before the musical world. I confess that I should have to consider it a rather useless employment of my time, if I had but added one more to the numerous hitherto published piano-arrangement, following in their rut; but I consider my time well employed if I have succeeded in transferring to the piano not only the grand outlines of Beethoven’s compositions but also all those numerous fine details, and smaller traits that so powerfully contribute to the completion of the ensemble. My aim has been attained if I stand on a level with the intelligent engraver, the conscientious translator, who comprehend the spirit of a work and thus contribute to the knowledge of the great masters and to the formation of the sense for the beautiful.

(Franz Liszt, Rome 1865 – English translation by C.E.R. Mueller)

Many moons ago, as I tucked wearily into a slice of stale quiche in an elderly stranger’s house far away from home, my energy spent from the recital I’d just given and my concentration engaging only sporadically with the discussion about hip replacements and supermarket prices on-going around me, an inquisitive and unsuspecting gentleman asked me to articulate exactly what I wanted from my career. Suddenly energised by what I considered a probing enquiry, I waffled away for many merry minutes, ignoring the glazed looks that crossed the faces of all who listened and gleefully grasping the opportunity to steer conversation away from Morrison’s latest 3 for 2 offer. I listed all the things that genuinely interested me: the odd concerto, recitals full of quirky repertoire, chamber music (with an unrealistically long list of musical collaborators), festival programming, recording, masterclasses and teaching, presentations and on-stage interviews. It was, I confess, a very long-winded monologue, and the benefit of maturity and hindsight has taught me I could – and probably should – have saved my not-so-captive audience a great deal of time and tedium by condensing my bout of verbal diarrhoea to just two words: variety and fun. Unfortunately, as it happened, I never did get to hear how long it’d take Phyllis to be rid of her crutches.

One thing’s for certain: at the time of that misguided ramble I couldn’t have imagined my career would one day become so varied that I’d make an annual visit to Restoration House in Rochester to perform on a fortepiano, nor indeed that I should have so much fun when doing so. I readily admit to having no education and very little experience in playing period instruments. Yet, despite my co-ordination and orientation taking a battering from the resident Girikowsky’s reduced compass, and regardless that my feet have been scarred by countless lengthy splinters from the Great Chamber’s 19th Century floorboards (an extra foot pedal means my oversized plodders must go shoeless), I’ve played every single concert there with a broad grin and a soul refreshed from my daily confrontations with modern Steinway grands and shiny new concert halls. So varied – and valuable – is this departure from my ‘normal’ career, I truly consider it one of the highlights of my calendar.

The “Pastoral” has, quite simply, been my favourite symphony for as long as I can remember. I recall childhood holidays spent driving through mountainous scenery, the ‘Storm’ blasting from the car stereo, my arms air-conducting hysterically in a manner unintentionally recalling a hapless victim from the film Jaws. God only knows what passing motorists must have thought. I’m fairly certain I’ll never stand before an orchestra and revive my juvenile attempts to beat time, so I can only express huge gratitude to Liszt for having the mind-boggling skills to transcribe the piece for piano, and to Jonathan and Robert, custodians of Restoration House, for displaying the courage and sense of adventure required to let me perform it on their fortepiano.

Ever since my first visit to Restoration House, we’ve always agreed on one key ingredient to my recital programmes: that they should contain works which are not ordinarily associated with a keyboard instrument dating from the 1820s. We’ve gradually worked our way through a vast range of repertoire, each new experiment bringing a sense of excitement and anticipation. It’s probably fair to say not every choice has worked, but on many occasions the temperament, texture and timbre of the Girikowsky has engaged with the music to reveal colours and characters unavailable to the modern piano. And, despite any initial concerns and reservations, I sincerely feel this to be the case with the “Pastoral”: one has the sense – I think – of fortepiano, fortepianist and composition all being stretched to their limits in a unique combination that delivers drama, immediacy and dynamism in spades.

I know this disc will not be for everyone. Transcriptions by themselves are often a rather taboo topic, especially when the transcribed work in question is something as endearingly popular as the “Pastoral”. Throw a fortepiano into the mix – particularly when played by a man who treats it like a 20th Century grand – and I can only imagine a polarized reaction similar to that which generally greets Marmite. With this in mind, I must offer huge thanks to Orchid for sharing my faith in this project, to Jools for his enthusiasm and his kind offer to write an introductory note, to Mike Ponder my long-standing (long-suffering?) friend and producer, to Ed Pickering, tuner extraordinaire, who was on hand to nurse the Girikowsky back to health each time I broke it, to the Girikowsky itself for having the tenacity and courage to withstand my ferocious assault, and – most of all – to Jonathan and Robert for their endless generosity, encouragement and support.

I can only hope this recording captures some of the fun we had when making it.

© Ashley Wass, 2012

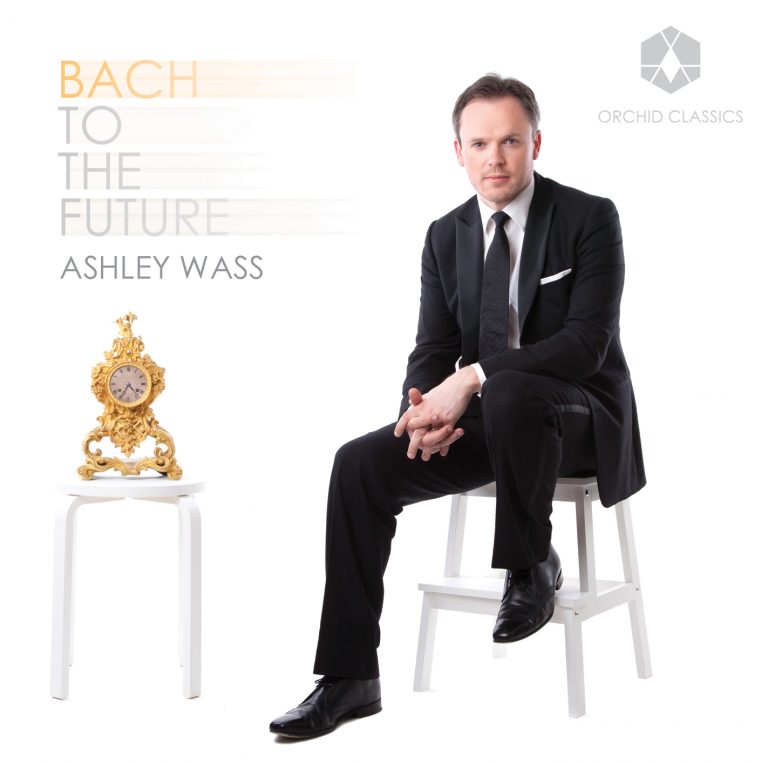

ASHLEY WASS

‘A thoroughbred who possesses the enviable gift to turn almost anything he plays into pure gold’

(Gramophone Magazine)

Described as an ‘endlessly fascinating artist’, Ashley Wass is firmly established as one of the leading performers of his generation. He is the only British winner of the London International Piano Competition, prizewinner at the Leeds Piano Competition, and a former BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist.

Increasingly in demand on the international stage, Ashley has performed at many of the world’s finest concert halls including Wigmore Hall, Carnegie Hall and the Vienna Konzerthaus. He has performed as soloist with numerous leading ensembles, including all of the BBC orchestras, the Philharmonia, Orchestre National de Lille, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, RLPO, and under the baton of conductors such as Simon Rattle, Osmo Vanska, Donald Runnicles, Ilan Volkov and Vassily Sinaisky.

In June 2002 he appeared alongside the likes of Sir Thomas Allen, Mstislav Rostropovich and Angela Gheorghiu in a gala concert at Buckingham Palace to mark the Golden Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, a performance broadcast live to millions of viewers around the world. In recent years he has become a regular guest at the BBC Proms, making his debut in 2008 with Vaughan Williams’ Piano Concerto, and returning in following seasons to perform works by Foulds, Stravinsky, Antheil, and McCabe.

Renowned for a broad and eclectic repertoire, Ashley has received great critical acclaim for his recordings of music from a wide range of styles and eras, with glowing reviews of his interpretations of composers such as Liszt, Franck, Beethoven and Bridge. His survey of Bax’s piano music was nominated for a Gramophone Award and his discography boasts a number of Gramophone ‘Editor’s Choice’ recordings and BBC Music Magazine ‘Choices’.

Much in demand as a chamber musician, Ashley regularly partners many of the leading artists of his generation. He is a frequent guest of international festivals such as Pharos (Cyprus), Bath, Ako (Japan), Cheltenham, Kuhmo, Mecklenburg, Gstaad, City of London, and Ravinia and Marlboro in the USA, playing solo recitals and chamber works with musicians such as Mitsuko Uchida, Steven Isserlis, Emmanuel Pahud, Richard Goode and members of the Guarneri Quartet and Beaux Arts Trio.

Ashley Wass is the Artistic Director of the Lincolnshire International Chamber Music Festival. The Festival has grown from strength to strength during his tenure, with sold-out performances of challenging repertoire and broadcasts on BBC Radio 3.

Ashley is currently a Professor of Piano at the Royal College of Music, London, and is an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music.

www.ashleywass.com

www.facebook.com/AshleyWassPiano

Twitter follow @ashley_wass

‘It is difficult to point to an orchestral ‘Pastoral’ more moving than this…’ (International Record Review, November 2012)