Artist Led, Creatively Driven

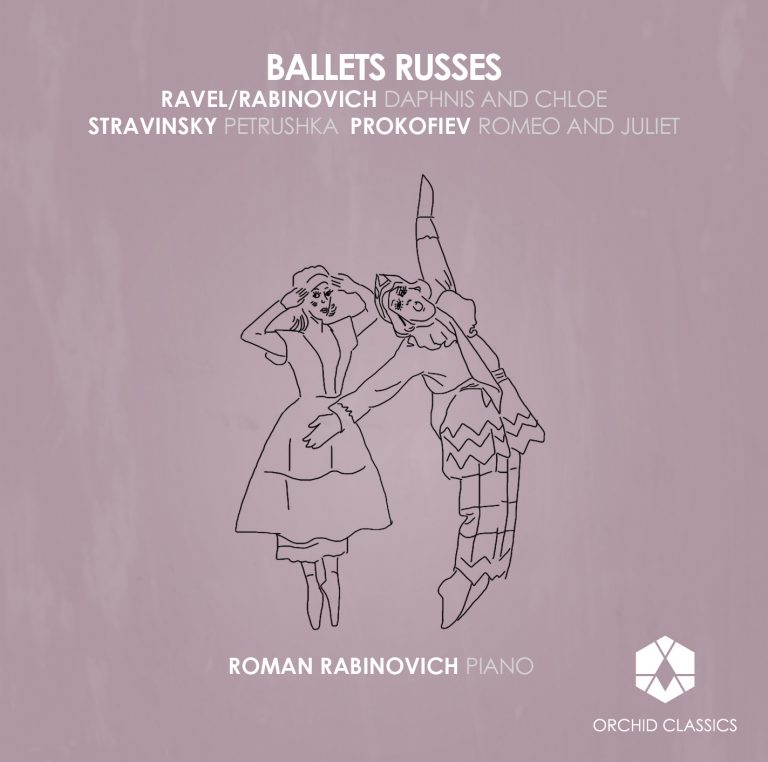

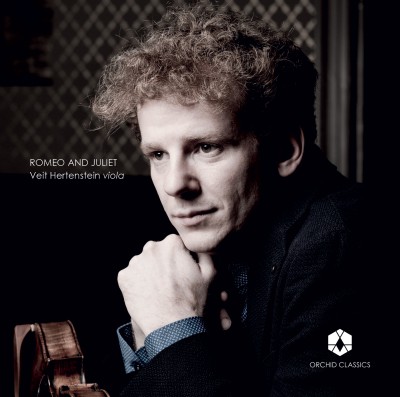

Romeo and Juliet

Veit Hertenstein, viola

Release Date: 1st September 2016

ORC100057

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Excerpts from ’Romeo and Juliet’ trans. for viola (two violas) and piano by Vadim Borisovsky

1. Introduction 2’24’’

2. The Street Awakens 1’31’’

3. Morning Serenade 2’22’’

4. Juliet as a Young Girl 3’06’’

5. Arrival of the Guests 3’12’’

6. Dance of the Knights 5’30’’

7. Carnival 3’36’’

8. Balcony Scene 5’31’’

9. Mercutio 2’26

10. Dance with Mandolins 1’46’’

11. Death of Mercutio 2’35’’

12. Romeo and Juliet meet Friar Laurence 6’41’’

13. Death of Juliet 7’06’’

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

14 Preludes from Op.34, trans. for violin and piano by Dmitri Zyganow, arr. for viola and piano by Veit Hertenstein

4 Preludes

14. Op.34 No.10 Moderato non troppo 1’57’’

15. Op.34 No.15 Allegretto 57’’

16. Op.34 No.16 Andantino 1’10’’

17. Op.34 No.24 Allegretto 1’14’’

10 Preludes

18. Op.34 No.2 Allegretto 56’’

19. Op.34 No.6 Allegretto 1’09’’

20. Op.34 No.12 Allegretto non troppo 1’36’’

21. Op.34 No.13 Moderato 51’’

22. Op.34 No.17 Largo 2’06’’

23. Op.34 No.18 Allegretto 47’’

24. Op.34 No.19 Andantino 1’50’’

25. Op.34 No.21 Allegretto poco moderato 43’’

26. Op.34 No.22 Adagio 2’41’’

27. Op.34 No.20 Allegretto furioso 42’’

Total time: 66’31”

Veit Hertenstein, viola

Peijun Xu, 2nd viola (track 3 and 10)

Peiyao Wang, piano

“I do not remember exactly when I first saw Prokofiev, I only know that at some point during the rehearsals of Romeo and Juliet I became aware of the presence of a tall, somewhat stern-looking man who seemed to disapprove heartily of everything he saw and especially of our artists. It was Prokofiev.”

As the Soviet ballerina Galina Ulanova, who danced Juliet in the Kirov production of Prokofiev’s ballet, recalled, the composer could be a forbidding and intimidating presence, with a meticulous, demanding approach to productions of his music. Yet Prokofiev praised the Kirov production, explaining his reservations in terms of the choreography rather than the dancers themselves:

“The Kirov Theatre produced the ballet in January 1940 with all the mastery for which its dancers are famed – although with some slight divergences from the original version. One might have appreciated their skill more had the choreography adhered more closely to the music. Owing to the peculiar acoustics of the Kirov Theatre and the need to make the rhythms as clear-cut as possible for the dancers I was obliged to alter a good deal of the orchestration.”

Prokofiev had finished the first version of the score to Romeo and Juliet in 1935, and the premiere took place in a provincial theatre in Brno, in what is now the Czech Republic. The composer was initially cautious about having the work staged after Shostakovich and others received sinister criticism from the Russian State newspaper, Pravda. However, Prokofiev went on to arrange two suites from the ballet music (the full score boasts some 52 numbers), before a friend of the composer, and of Shostakovich, Vadim Borisovsky, presented this music in another fresh guise: as a selection of movements for viola and piano. The movements were published in two batches, firstly in 1961, and then in 1977. Borisovsky was the violist of the Beethoven Quartet between the early 1920s and 1964; and the versatile tone of the viola lends itself beautifully to Prokofiev’s original material.

The Introduction features Prokofiev’s distinctive harmony and sinuous melodic lines, which trace a path between hope and melancholy to convey the combination of young love and tragedy found in Shakespeare’s play. In his working notes, to which he referred during rehearsals, Prokofiev wrote of ‘The Street Awakens’ that: “The street comes to life. People emerge, meet. Belated strollers return home. The mood is carefree”. Prokofiev’s jaunty music is realised by Borisovsky with the viola’s pizzicato, double stopping and harmonics.

‘Morning Serenade’ features two violas, with chirpy pizzicato and light piano-writing. The frenetic opening of ‘Juliet as a Young Girl’ translates into passages of thrilling virtuosity for both viola and piano, contrasted with moments of lyricism. Prokofiev described the scene: “Juliet enters running. She is only 14 years old. She jokes and frolics like a little girl, and does not want to get dressed for the ball. Still, the Nurse manages to get her into her ball-gown. Juliet in front of the mirror. She sees a young woman in it and falls to thinking. Juliet runs out.”

Setting the scene for the vibrant ‘Arrival of the Guests’, Prokofiev wrote: “The guests arrive in huge opera-cloaks and shawls. The dance consists of unfastening and taking off these shawls. Guests constantly disappear into the inner rooms”. The famous ‘Dance of the Knights’ presents the Montagues and Capulets preening to imposing, threatening music, with more graceful interludes, featuring gossamer viola harmonics lightening the mood of foreboding. Prokofiev imagined the knights as “ponderous, in armour. The ladies dance. The men dance. Juliet dances in a formal and indifferent way with Paris. Romeo watches admiringly; gradually the general dancing starts up again.”

The energetic and witty ‘Carnival’ uses material from the ballet’s ‘Dance of the Five Couples’, about which Prokofiev wrote, “… the movements are tiny and very delicate. A cheerful procession with a brass band makes its way along the street. The dance resumes.”

During the ‘Balcony Scene’, “Juliet enters in her nightgown. She searches for a kerchief or a flower dropped during her meeting with Romeo. Romeo appears from behind a column. The love dance begins.” Prokofiev’s music here is amongst the most sensuous in the ballet, articulated by the viola’s long-breathed lines which seem to ache with longing. The skittish ‘Mercutio’ episode provides the violist with ample opportunity to paint a portrait of this playful, complex character. Prokofiev summarised the movement: “Mercutio greets [Romeo] and teases him.”

Borisovsky’s arrangement of the ‘Dance with Mandolins’ features two violas to create a full, jangling texture. The ‘Death of Mercutio’ begins with arresting, astringent double-stopping in the viola against the piano’s ominously repetitive, funereal rhythms. The sonority of the viola seems perfectly suited to this material, with haunting harmonics and stalking pizzicato enhancing the eerie atmosphere.

When ‘Romeo and Juliet Meet Friar Laurence’, Prokofiev relates how “Laurence gives her the potion. Juliet is ready, soothed, and even enthusiastic. Juliet goes out, growing up into a tragic figure”. This bittersweet movement has a gentle, ponderous quality, reflecting the character of the Friar. Finally, the ‘Farewell before Parting and Juliet’s Death’ brings the suite to a tragic conclusion. The movement opens with the piano’s low-pitched, almost Debussyan textures, answered by a fulsome, painfully hopeful viola melody. Yet the ending of the work, as the lovers breathe their last, avoids bleakness; rather, it is exquisitely delicate. The effect is far more heart-breaking than full-blown drama.

Summarising the significance of Romeo and Juliet, Leonid Lavrovsky, who choreographed the Kirov production, wrote:

Prokofiev carried on where Tchaikovsky left off… He was one of the first Soviet composers to bring to the ballet stage genuine human emotions and full-blooded musical images. The boldness of his musical treatment, the clear-cut characterisations, the diversity and intricacy of the rhythms, the unorthodoxy of the harmonies – all these elements of Prokofiev’s music, particularly in Romeo, serve to turn a performance into a dramatic entity.

In 1927, Dmitri Shostakovich admitted that, “Generally speaking, I composed a lot under the influence of external events”. Yet his 24 piano Preludes, Op.34, are unusual for being relatively self-contained, a characteristic which renders them more easily adaptable to transcription. Shostakovich’s earliest piano works are often acerbic, but the Preludes, written between 1932 and 1933, are warmer pieces, audibly influenced by Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives. Shostakovich strove in these works to bridge the gap between his own musical language and the genre’s stylistic precedents, as found in the Preludes by Bach, Chopin, Rachmaninov and Debussy, among others.

Dmitri Zyganow’s violin and piano transcription (adapted here for viola by Veit Hertenstein) divides the Preludes into two sets: Nos. 10, 15, 16 and 24; and Nos.2, 6, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22 and 20. The first set begins with No.10, in C-sharp minor, in which a Russian Romanticism redolent of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov is punctuated by sardonic interjections. No.15 in D-flat major is a frenetic waltz, followed by a rather hysterical march, in B-flat minor, No.16. This unhinged quality can also be found in No.24, in D minor, its maniacal, warped character creating that grim humour at which Shostakovich excelled.

The second set begins with the Prelude No.2 in A minor, a skittish waltz, followed by the humorous Prelude No.6, in B minor, with its angular motifs. The enervating Prelude No.12 in G-sharp minor is characterised by its sense of perpetual motion, before a tonally ambiguous ending. In No.13, in F-sharp major, a gentler humour is created with the contrasts in pitch between a singing viola line and growling piano. The Prelude No.17 in A-flat major – Romantic in spirit but leavened by distorted gestures – is followed by the nervy F minor Prelude, No.18.

In No.19 in E-flat major, a rocking piano accompaniment underpins the viola’s lyrical, impassioned melody. The intricate Prelude No.21 in B-flat major is playful and complex, with a concise, witty ending, and No.22 is a melancholic piece exploiting the piano’s spatial qualities, as well as the viola’s plangent tone. The arrangement ends with the frantic C minor Prelude, No.20, in which Shostakovich issues forth a burst of fiery material – extinguished with comedic rapidity.

The intimacy of works such as these Preludes, which reveal Shostakovich’s character in a way that larger-scale works cannot, was praised by Benjamin Britten when he paid tribute to Shostakovich in 1966, on the occasion of the latter’s 60th birthday:

… much as I admire the Symphonies and the opera, to me Shostakovich speaks most closely and most personally in his chamber music. There is a time in every artist’s life when he wishes to communicate intimate thoughts to a few friends – and I do not mean only his actual friends, but people unknown to him, who have souls sensitive to his (people from all over the world, whatever race or colour). And for this one doesn’t need the mass of full chorus or orchestra and the big halls and theatre, but small groups of performers and small halls, sometimes only private rooms.

© Joanna Wyld, 2015

One of the most exciting musicians on his instrument to emerge in years, German violist Veit Hertenstein plays with “admirable precision, dedication and strong musical expression“ (Augsburger Allgemeine 2013) as well as “maturity, technique, thoughtful musicianship, and a tone of dark honey” (The Boston Musical Intelligencer 2013).

Mr. Hertenstein has been invited to the Marlboro Music Festival, the Seiji Ozawa International Music Academy, the Viola Space Festival Tokyo, Menuhin Festival in Gstaad and the Verbier Festival, where he was awarded the “Henri Louis de la Grange” viola prize. He has also been several times invited to the La Folle Journée Festival in Nantes and Tokyo.

As a chamber Musician he collaborated with Trio Wanderer, Modigliani and Ysaye Quartets, Brigitte Engerer, Valentin Erben (Alban Berg String Quartet) and with Midori.

In the United States Mr. Hertenstein performed in concert halls such as The Merkin Hall, New York, The Kenendy Center in Washington D.C. after winning First prize as well as eight performance prizes in the Young Concert Artists International Auditions 2011 in New York City.

Mr. Hertenstein has won several prestigious competitions. In 2009 he was the first violist to win the New Talent Competition of the European Broadcasting Union in Slovakia founded by Yehudi Menuhin, which was followed by world-wide radio broadcasts. He was a prize-winner of the first Tokyo International Viola Competition 2009. In 2007 he was the first violist to win First Prize at the Orpheus Competition in Zurich, Switzerland.

Pro Helvetia commissioned a Viola Concerto by Swiss composer Nicolas Bolens which was premiered in Geneva 2014.

Born in Augsburg, Germany, Mr. Hertenstein began studying the violin and piano at the age of 5 and switched to the viola when he was 15. In 2009 he graduated with distinction from the Haute Ecole de Musique in Geneva, where he worked with violist Nobuko Imai. He also has been artistically influenced by György Kurtag, Krzysztof Penderecki, Gabor Takács-Nagy, Yuri Bashmet and Kim Kashkashian.

In 2011 Mr. Hertenstein became the principal violist of the Basel Symphony Orchestra in Switzerland.

In October 2015 he became a professor at the Hochschule für Musik in Detmold, Germany.

Taiwanese American Pianist Pei-Yao Wang has established herself as a prominent soloist and chamber musician.

Since her official orchestral debut with the Taipei Symphony Orchestra at age 8, Ms. Wang has performed as soloist with the Stamford Symphony, Orlando Symphony and Taipei Philharmonic. She also has performed throughout the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia; including venues such as the Carnegie, Avery Fisher, Alice Tully, 92nd street Y, Merkin Halls in New York City, the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. Salle des Varietes in Monte Carlo, Suntory Hall in Tokyo and the National Concert Hall in Taipei, Taiwan.

As a chamber Musician, Pei-Yao has collaborated with members of the Guarneri, Orion, Chicago, Mendelssohn and Miro quartets; and has performed with other distinguished artists such as Claude Frank, Hilary Hahn, Nicola Benedetti, and Mitsuko Uchida. She is also regularly invited to perform at festivals including Marlboro, Caramoor, Chamber Music North West, La Jolla, Ravinia, and Bridgehampton in New York.

Peijun Xu, born in Shanghai, is widely recognised as among the foremost violists of her generation. She is the recipient of several international awards. In 2012 she was awarded the first prize and audience prize at the International Max Rostal Competition, Berlin. In 2010 she won first prize as well as two special prizes at the International Yuri Bashmet Viola Competition in Moscow, and in 2006 she was awarded second prize in the Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition.

As soloist Peijun Xu has performed at prestigious venues such as the Shanghai Concert Hall, Hamburg Laeiszhalle and Frankfurt Alte Oper. She has appeared with the Shanghai Philharmonic Orchestra, the Moscow Soloists, the State Symphony Orchestra ‘New Russia’, the Hofer Concert Orchestra, the Osnabru?ck Symphony Orchestra, Baden-Baden Philharmonie, Kurpfa?lzisches Chamber Orchestra , the Wurttemberg Chamber Orchestra, Heilbronn and the Hamburger Camerata, under conductors such as Muhai Tang, Yuri Bashmet, Pavel Baleff and Ralf Gotho?ni. Peijun Xu’s chamber music partners have included Paul Rivinius, Evgenia Rubinova, Mihkel Poll, Jens Peter Maintz, Alexander Sitkovetsky and Julian Steckel.

Peijun Xu’s debut CD including works of Bach, Schubert, Vieuxtemps, Chopin and Rebecca Clarke was released by Label Ars in 2012. It has since been broadcast by WestDeutscher Rundfunk, Bayerischer Rundfunk and Deutschlandradio Kultur. In August 2014, her second CD of works of Vieuxtemps, Milhaud, Faure? and Franck was released by Profil Ha?nssler.

Peijun Xu studied at the Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts with Prof. Roland Glassl, the Kronberg Academy with Prof. Nobuko Imai and the Berlin University of Music ‘Hanns Eisler’ with Prof. Tabea Zimmermann. Since 2011, Peijun Xu has held a viola teaching position at Frankfurt University of Music and Performing Arts.

My connection to Romeo and Juliet began already at a young age. At 7 years old I first discovered this wonderful Ballet music from the viewpoint of a dancer. In my mid twenties I was able to experience it further from within the orchestra where I was transfixed, open eared and stary eyed by the multitude of colors and intricate use of orchestration. It has always been my ultimate goal to bring out as much as possible these colors in Borisovsky’s version on the viola. To be able to combine all the many influences from my experiences as a dancer as well as a musician has enabled me to widen and develop my interpretation.

While searching for fitting music to Romeo and Juliette for a CD recording I stumbled across Dmitri Zyganow’s violin and piano transcription of the Prélude op. 34 by Shostakovich.

Shostakovich wrote to his friend Zyganow after hearing him play his transcription:

When I heard the pieces in this format I totally forgot that I originally wrote them for piano solo. They sounded so “violinistic“.

It is my ongoing wish that this viola version of the prelude, while favouring the darker tone colours when compared to the violin transcription would have recieved similar appraisal from the composer.

Veit Hertenstein

“A fascinating and rather enchanting album from violist Veit Hertenstein … puts the spotlight on this often-neglected instrument, as well as reimagining the vivid orchestral colours of the ballet in a more intimate, chamber-music form.”

– Presto Classical