Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Hélène de Montgeroult

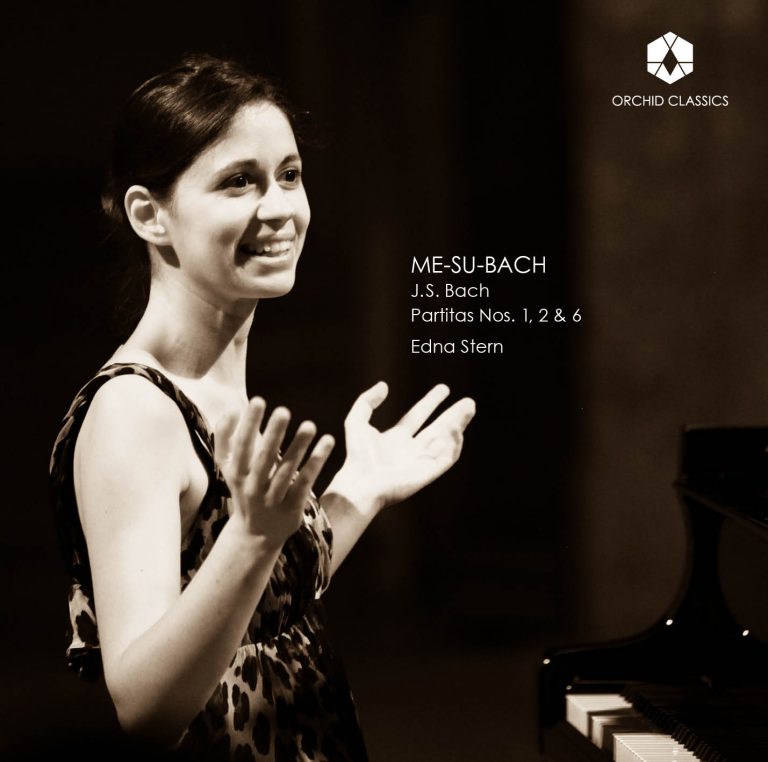

Edna Stern

Release Date: 1st February 2017

ORC100063

Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836)

Piano Sonata No.9 in F sharp minor Op.5 No.3

1. First movement : Allegro spiritoso 10’25

2. Second movement : Adagio non troppo 3’32

3. Third movement : Presto 5’28

4. Fugue No.1 in F minor 4’14

12 Etudes from Complete Course for the instruction of the pianoforte

5. Etude No. 7 in E minor 1’

6. Etude No. 17 in E flat major 1’36

7. Etude No. 19 in F major 1’09

8. Etude No. 37 in G major 0’49

9. Etude No. 26 in G major 1’28

10. Etude No. 28 in E major 2’20

11. Etude No. 55 in F minor 1’33

12. Etude No. 65 in E flat minor 1’07

13. Etude No. 66 in C minor 1’22

14. Etude No. 104 in G sharp minor 1’59

15. Etude No. 106 in E major 4’35

16. Etude No. 107 in D minor 1’50

17. Thème Varié dans le genre moderne 8’50

Total time 53’19

Recorded on a Pleyel 1860 Concert Grand from the collection of the Museum of the Cité de la Musique in Paris.

The rediscovery of Hélène de Montgeroult’s music, notably her Complete course for the instruction of the pianoforte (more than 700 pages, including 114 Etudes, varied themes, fugues, and a fantasy), which can be found in several of the world’s great public libraries, brings to mind Georges Perec’s short story The Winter’s Journey, in which a young man unearths a long-forgotten book that seems to anticipate Symbolist poetry avant la lettre, a book of “plagiarism by anticipation” that will vanish for good later in the story. The difference is that today, Hélène de Montgeroult’s work, still extant, is asserting itself as the missing link between Mozart and Chopin. Her personality, doubtless too modern for her contemporaries – who struggled to understand her audacious chord progressions and her rich and complex polyphony – now sheds light on the French music of the nineteenth century prior to Berlioz, as it touches listeners who are now familiar with the language of Romanticism. She sunk into oblivion soon after her death. However, it is hard to imagine any of the great Romantics (Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, Schumann, even Brahms) not having studied the piano on the basis of her method, who was popular at the time and was graced with a fourth reprint in Germany around 1830. And indeed, who would not think, for example, of Chopin’s “Revolutionary Etude” (Op.10/12) while listening to Montgeroult’s Etude No.107?

Hélène de Nervo was born in Lyon on 2 March 1764, but she grew up, a child prodigy, in Paris. Married at 20 to the 48-year-old Marquis of Montgeroult, she began playing exclusively in the salons, making a strong impression on her privileged listener. It was then forbidden for a person of noble descent to give public concerts or to publish under her own name. During the Revolution, her situation was fraught with danger. She endured a series of misfortunes: capture by Austrian soldiers and her later escape; the death of her husband; her return to Paris, only to be imprisoned. She owed her freedom to her improvisations on the Marseillaise performed in front of the Committee of Public Safety. Afterwards, her son was born, she was nominated to the Paris Conservatory (1795) and was the first woman professor ever to be nominated. A second, short-lived, marriage was followed by her resignation from the Conservatory and the onset of health problems. In favour of the Revolution, one might say, she made the bold move of daring to publish her nine sonatas. Her masterwork is the Complete course, which she probably started around 1788 and finished in 1812; it was published in 1816, and afterwards, it seems, she no longer composed. Again married in 1820, she was soon widowed for a second time. In 1834, while very ill, she left for Italy to undergo treatment, accompanied by her son, the great art collector His de La Salle, and died in Florence on May 20, 1836.

Her music is multifaceted in its styles, first inspired by venerable predecessors (Montgeroult designates among them J. S. Bach, Handel and Scarlatti). Her strong connection to Bach anticipates the Romantics. It is to this style’s category that we attach the Etudes No. 7 in E minor, No. 106 in B major, and No. 19 in F major, an homage to Bach’s First prelude from the well-tempered keyboard, where she reveals herself to be a magician in sound.

The Ninth Sonata in F# minor, is a reference to the Viennese classics. The Allegro spiritoso adopts a clear sonata form, with two themes, typical of this style. The Adagio non troppo seems to echo the Mozart of the piano fantasies, and the Presto takes again a bi-thematic sonata form. The third facet of her style, the prophetic one, shows her prescient romanticism, even though the great Romantic generation was born about fifty years after her, and Schubert was her son’s age. The aesthetic of the miniature form, or fragment, is central and constitutes the very heart of Romantic piano music: the form of the Etude is new and therefore favourable for all sorts of inventions and audacities. These Etudes are often fleeting moments that embody a pedagogical idea, and more importantly a profound show of musical invention. The First Fugue, composed in 1800, celebrates this form “from which science excludes neither the warmth nor the grace”, and the Varied Theme in modern style can be placed somewhere between Haydn and Schumann. The eleven variations show her genius in creating atmospheres with tools that are both subtle and discreet: restraint, ardour, the evocation of a daydream, and, in the final variation, a symphonic heroism.

C Jérôme Dorival, May 2016.

The pieces recorded here are published in the Éditions Modulation (editionsmodulation.com), and one can find out many more details and information at www.HélènedeMontgeroult.com

The biography Hélène de Montgeroult (1764-1836), La Marquise et la Marseillaise (2006), by Jérôme Dorival, is published by Éditions Symétrie.

Edna Stern, piano

“Her piano playing bears the mark of three great pianists who formed her and of whom she managed to create an improbable synthesis: The panache of Martha Argerich, the musicality of Leon Fleisher and the impeccable finish of Krystian Zimerman.” – Diapason Magazine

Edna Stern began her studies in Israel with Viktor Derevianko, a student of Heinrich Neuhaus. She continued studying with Krystian Zimerman at the Basel Hochschule and with Leon Fleisher at the Peabody Institute and at the Lake Como International Piano Foundation. Her recordings are highly praised by critics, receiving such awards as Diapason d’Or, Diapason Découverte, Arte Best CD, Gramophone upcoming artist, and selection by Le Monde of best classical CDs for the years 2010 (Mozart Concerti/Zig-Zag Territoires) and 2014 (Beethoven Sonatas/Luna). She has performed at prestigious halls and festivals such as the Olympia in Paris, la Roque d’Anthéron Festival, Concertgebouw of Amsterdam, Munich’s Hekulessaal, Paris’ Châtelet Theater, Moscow’s Music-House, Petronas in Kuala Lumpur and Musashino hall in Tokyo; performing in solo recitals and with orchestras, with conductors such as Claus Peter Flor and Andris Nelsons. Stern gives masterclasses all over the world, including at the CNSM Paris, Rutgers University and Tel-Aviv Zubin Mehta School of Music. She has been a Professor at the Royal College of Music, London since 2009.

“…it [the album] uncovers the strangely paradoxical distance, like a drawn cross bow, between the science of the counterpoint, and the art of the rubato in this musician’s work.” – Figaro, February 2017

“Chopin’s C minor Étude sounds less Revolutionary after you’ve heard de Montgeroult’s swirling Étude No 107, which anticipates it by 20-odd years.”

– The Guardian, January 2017

Perfumed and poised in equal measure…

… A sprightly, smiling joy in her playing… …historically valuable… – Pianist Magazine