Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Through the Lens of Time

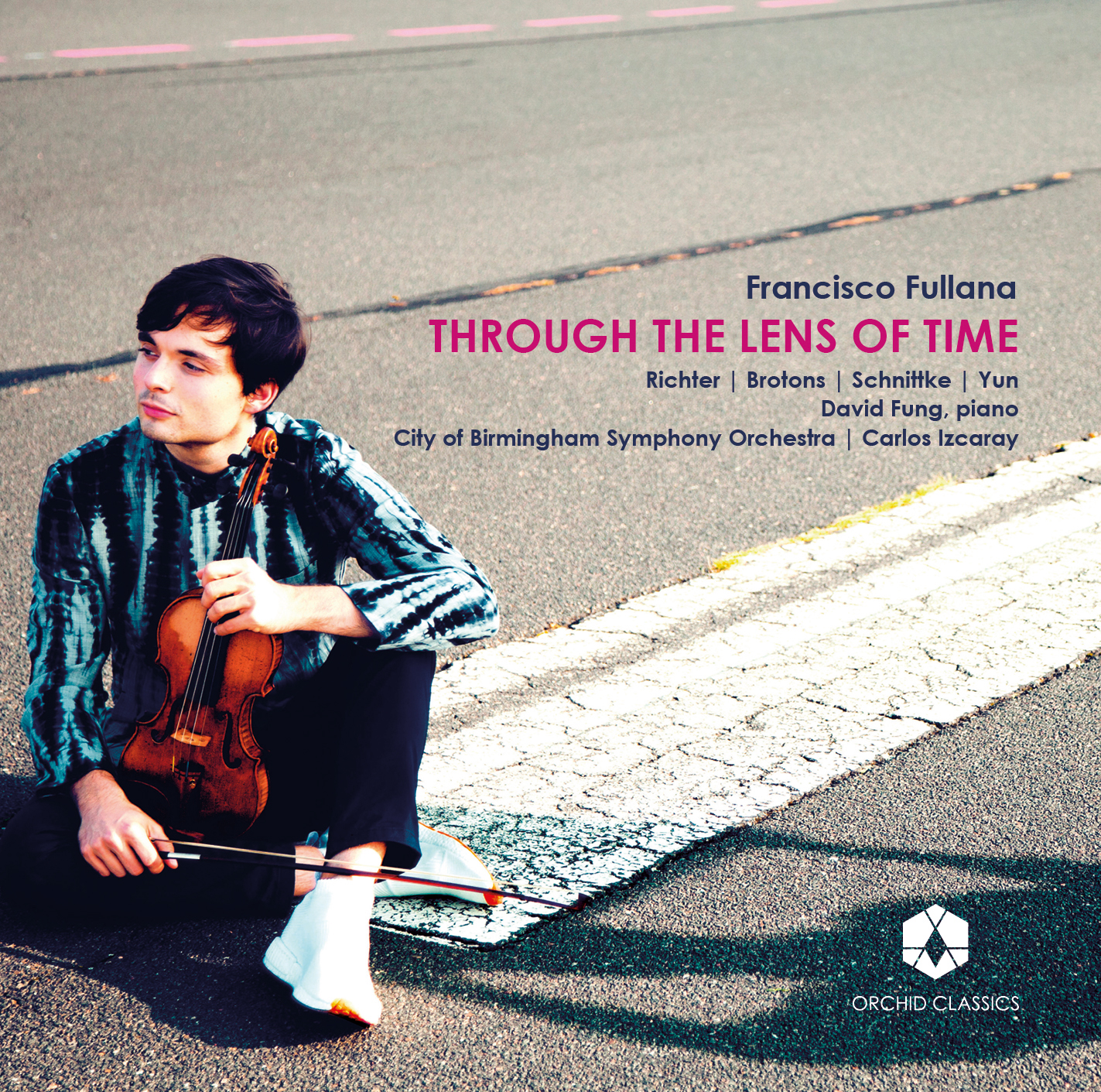

Francisco Fullana, violin

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

Carlos Izcaray, conductor

David Fung, piano

Release Date: March 2nd 2018

ORC100080

THROUGH THE LENS OF TIME

Max Richter (b.1966)

The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Spring

1. I 2.42

2. II 4.01

3. III 3.18

Isang Yun (1917-1995)

4. Königliches Thema for solo violin 7.43

Max Richter

The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Summer

5. I 4.07

6. II 4.23

7. III 3.37

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998)

Suite in the Old Style for violin and piano*

8. I Pastorale 3.25

9. II Ballett 2.25

10. III Menuett 2.52

11. IV Fuge 2.46

12. V Pantomime 3.28

Max Richter

The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Autumn

13. I 6.18

14. II 3.23

15. III 1.41

Salvador Brotons (b.1959)

16. Variacions sobre un tema barroc for solo violin 6.02

(World premiere recording)

Max Richter

The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Winter

17. I 3.04

18. II 2.48

19. III 5.12

Total time 73.21

* David Fung, piano

I invite you to join me on a musical journey that stands at the crossroads between musical paths. Through the Lens of Time brings together four modern perspectives reimagining the Baroque tradition: a dialogue between Old and New that prompts both composers and performers to explore music from giants of the past and its place in their own lives.

Vivaldi and Bach’s melodies inspired by Chris Potter’s saxophone and the twelve-tone system; from the Roman Pantomime to Soviet cartoons, are you ready to come on a musical adventure through the centuries?

Francisco

Through the Lens of Time

Life is full of coincidences, seemingly meaningless and isolated events that on their own are just that, meaningless, but when combined have the power to shape a person’s life. In the case of musicians, our path and artistic approach is constantly being affected by the many ever-changing factors that shape our emotions and outlook on life: personal experiences in the realms of love, family and friendship, inspiring collaborations with other musicians and encounters with new works that resonate with something deeper, helping us discover the unknown within ourselves.

Take out any one of hundreds of these moments, and chances are I would not be here today, writing these notes tucked in a corner of my favourite cafe in the Upper West Side of Manhattan on a windy autumn morning. Call it the butterfly effect, call it luck. When I come to think of it, the fact I even started playing the violin is sort of a coincidence: my Mom bought me a plastic yellow toy violin at age three. I liked playing with it and from there, my parents decided to find a music teacher. I got lucky, who knows what would have happened if Bernat Pomar, by far the best music pedagogue my hometown of Palma de Mallorca has ever seen, taught a different instrument instead of the one that has become my life.

The concept for this album started with a couple of these “moments”: two seemingly separate conversations about a week apart from each other in early 2015. The first one was a phone call from the artistic director of the Chamber Orchestra of San Antonio: “I have the perfect piece for you. Max Richter’s The Four Seasons Recomposed. It has your character written all over it, and trust me, you will thank me later. Let’s do it next Spring.” About a week later, I was finalizing a concert programme centred around Bach’s masterful Chaconne, and I was looking for one more piece to pair with it. In a casual subway conversation among musicians in New York, my friend brought up this “crazy piece, it’s amazing but good luck learning it.” And so: Isang Yun’sKönigliches Thema.

After learning and understanding Yun’s devilish work, I started performing it alongside Bach’s Chaconne during the 15/16 season. There was something so exciting about getting the audience to explore the connection between the two. I soon realized how deep the connections between both styles were, motivating me to research some more and to start obsessing over them. These bridges between the Baroque tradition and music written in the past century have become a big part of my path as an artist and this album takes me one step further in that direction.

Spring of 2016 came around and I started preparing Richter’s work, a brand new piece for me that aligned with this newfound obsession. Richter’s The Four Seasons Recomposed brought to me this raw, primitive reaction when playing the piece: a renewed commitment to my musical approach focused on instinct, intensity and raw emotion. It was bringing me back to my own beginnings, reviving that fearlessness that I had playing the violin as a youngster, thankfully without forgetting my years of training and experience. Richter himself is going back to his own childhood, to his love for Vivaldi’s Four Seasons as a kid. He describes his piece as an “act of love towards this fantastic masterpiece.”

Who hasn’t grown up with Vivaldi’s colourful melodies and loud barks in the Spring or the sleepy drunkards in the Autumn? The Four Seasons was one of the few cassettes (yes, those rectangular things with tape in them, remember?) that my family would play in the car, sometimes seemingly on loop. From getting dropped off at the conservatory in Madrid, to road trips through Asturias’ green canyons, and regular weekend escapades through the narrow roads of the Sierra de Guadarrama: Perlman, Stern, Mintz and Zukerman, each one making Vivaldi his own, while I looked out the window from the back seat of a white Renault Kangoo.

“For me, the work is trying to reclaim the piece, to fall in love with it again”, Richter states. Here lies the soul of the The Four Seasons Recomposed: those melodies, those rhythms, they are a cornerstone of the Western music tradition for almost 400 years and they had become the soundtrack of my childhood. That memory is intensified by Richter’s insatiable repeats and loops of Vivaldi’s material, bringing us back to the first time we ever heard them as children.

One last conversation was needed for this album to happen, this time with Carlos Izcaray, the conductor on the recording. He conducted the Richter performance in San Antonio. We both share the same energetic and committed approach to music making, and it was the perfect fit. After the performance on that fateful weekend, we sat down for a quick coffee. One thing became clear: we both loved performing this piece too much not to do so again. The rest is history.

So here we are: three conversations that shaped not just this album, but three moments that are shaping my musical path moving forward. The result is Through the Lens of Time, a dialogue between the Baroque and the Modern world. Richter’s edgy recomposition on the Four Seasons is intertwined with three works that serve as the connective tissue between each of the seasons. Together, they provide four unique takes on a discussion across three centuries that only keeps getting more interesting. One can say it all started with that recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, as a 10 year old kid with a whole lot of dreams and endless energy. Fortunately, neither the dreams nor the energy have gone away. My only wish with this album is that, you, the listener, will be able to hear some of these conversations through time and connect them to some of your own moments that shape who you are today. I would never intend to impose my feelings or reactions to these pieces onto you, those are up to you to figure out: that’s the beauty of this universal language we call music.

Max Richter (b.1966)

The Four Seasons Recomposed

Max Richter describes his recomposition of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons as an “act of love towards this fantastic masterpiece.” He brings us back to his childhood: an innocent and naïve attitude towards one of the most celebrated works in the history of classical music and the cornerstone of the Baroque tradition in Italy.

Richter’s feelings towards the original Four Seasons shifted over the years. “As a child, I fell in love with it. It’s beautiful, charming music with a great melody and wonderful colours. Then, later on, as I became more musically aware […] I found it more difficult to love it. We hear it everywhere. [This] work is trying to reclaim the piece, to fall in love with it again.”

The recomposition is in many ways just that, a personal reorganization of Vivaldi’s material: Richter keeps the same structure of the four separate concerti that Vivaldi wrote, each one with the traditional three movements, fast-slow-fast. The instrumentation is also almost the same, strings and harpsichord, with the addition of the harp.

The listener is in for a surprise with the opening movement of Spring: by looping the opening bars of the first solo in Vivaldi’s Spring, Il Canto degli Uccelli, Richter is making a statement, bringing us into his sound world of loops and minimalist gestures in an endless echo chamber. One can only describe Spring 1 as diving headfirst into the middle of a forest, populated by colourful birds that are singing all at once. Each animal has a specific call, started by two single violins as a quiet whisper. Each of the violin parts, eight in total, progressively joins in, imitating the various calls and growing into a musical shouting match. After the opening five bars, the rest of the orchestra joins in with a series of long held chords. These evocative harmonies add verticality to the movement, tree-like pillars that lead the constant expansion until the end.

If the The Four Seasons Recomposed were a book, Spring 1 would serve as its colourful cover, ready to be picked out from the shelf: it challenges the listener to step away from any assumptions they had of the piece’s connection to Vivaldi. And for every cover there is a back cover: if Spring 1 is constructed as a constant crescendo and sets the wheels in motion, Winter 3 brings the listener back to earth. Along the same lines as the opening movement, Richter loops and repeats material from Vivaldi’s Winter, replicating the sonority of the Correr Forte (Run Fast) section in the original. A mantle of sound is created by combining eighth-note patterns with long sustained notes. Richter chooses to stagger these patterns in 12-bar phrases, each line starting in different places. On top of this texture, the original 10-bar solo line is extended into a 16-bar phrase, repeating it 12 times, almost like a broken record. After varying amounts of activity, the movement unravels until it vanishes, as if the piece were just a dream.

Spring 2 introduces a very different side of Richter: one that shows utter reverence for the melodies of Vivaldi’s slow movements. These precious jewels contained within each of the Seasons are left almost untouched in all four slow movements, highlighting the beauty and lyricism of the original writing. Richter leaves Autumn’s evocative slow movement untouched from the original, as well as the solo violin line of Winter 2. He adds a simple instruction: ad libitum. Richter is putting the focus on the performer, letting the solo violin explore the unknown over the sustained chord of the orchestra.

The Four Seasons Recomposed is also so much more than a simple reorganization: Richter’s sense of innovation and his desire to borrow from other genres brings to the foreground his take on the modern musical world. Soaring new melodies, such as the ones that carry Summer 1 and 3 to climaxes, are overlapped onto Vivaldi’s motifs: Richter’s writing dares the soloist to look for a sound that would be unknown to the musicians of the 18th century. Strings wound in metal, heavier bows and a higher string tension, all standard today, allow the modern performer to find a completely different palette of sounds to that which was available to the players of the 18th century. Exaggerated vibrato, flat hair, and intense pressure are some of the techniques that can make the instrument on which I perform, the 1735 “Mary Portman” Guarneri violin, sound as though it is plugged into an amp more suited for a rock concert in Wembley Stadium than for a traditional concert hall. Modern composers take full advantage of such tools now at their disposal, with the sort of results I mean to highlight in this recording.

Max Richter’s sonic world forges a kaleidoscope of his life: a collection of his previous encounters with all kinds of music. Classically trained at the Royal Academy of Music, Richter draws inspiration from many sources, from some of the great masters like Bach and Vivaldi to punk rock and ambient electronica. Since his childhood obsession with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on Disney’sFantasia, Richter was fascinated by “sound and music in all its forms”. A “complicated modernist” during his early composing days, Richter worked extensively with Italian composer Luciano Berio, who encouraged him to simplify his writing. He established himself as a pianist in London, founding the six piano ensemble Piano Circus. While keeping his focus on performing, Richter kept writing and exploring the world of electronics and minimalism. Through collaborations with Future Sound of London and the album Memoryhouse recorded by the BBC Philharmonic, his identity as a composer blossomed: Richter’s ground breaking projects have been experienced by audiences all over the world, from his eight-hour long work Sleep in collaboration with neuroscientist David Eagleman to the soundtrack for the Golden Globe-winning film Waltz with Bashir.

Two elements are central to Richter’s sound world – sonorities that highlight his connection to the world of jazz and irregular metres and virtuosic fast note passages inspired by electronica. The end of Winter 1 fuses both of these elements, creating a highly explosive musical cocktail. This virtuosic ending constitutes one of the most challenging places for the soloist, a labyrinth of patterns in which the performer’s hand coordination must keep up with the writing’s rapid pace: 7/8 metre, 32nd notes, and pure craziness. On a personal note, this moment brings me back to my undergraduate days at The Juilliard School: as a 17-year-old freshman, I was exposed to live jazz for the first time by a few classmates from the Jazz department. They invited me to go watch a show at The Jazz Gallery, known for its progressive jazz shows and its eclectic vibe. I was in for a treat: the lead man of the band at the saxophone was playing like nothing I had ever heard before. An intensity and virtuosity I have never seen since, runs so fast it made your head spin. He played everything so effortlessly, seemingly summoning Paganini himself. The saxophonist was Chris Potter, a legend in the jazz world and someone I always think of whenever I perform this spot. I simply try to evoke the way he would play it on the saxophone: feeling the groove and taking the listener over the edge and back again.

In a few words, Max Richter’s The Four Seasons Recomposed is simply a conversation over the centuries. Paying homage to Vivaldi, he uses the Italian’s masterwork as a starting point for a dialogue between Tradition and Modernity: Richter takes the listeners on a journey, straddling the familiar and the unknown, taking surprising turns and making connections through different eras, genres and styles. He forces both performers and listeners to question and break through the artificial walls we all create for ourselves. By exploring new musical frontiers, The Four Seasons Recomposed provokes the listener to walk away with essential questions about the concept of “classical music” and what kind of expectations those two words evoke.

Isang Yun (1917-1995)

Königliches Thema for solo violin

The art of conversation is the undercurrent that flows through both Richter’s Four Seasons and the rest of the works on this album. Conversations between the new and the old, in different languages, with different ideas, but sharing a common respect for the Baroque tradition. As Richter puts it, “My piece doesn’t erase the Vivaldi original. It’s a conversation from a viewpoint, I think this is just one way to engage with it.” Richter is looking back through a lens that is crowded with shadows from the digital age, the modern world and almost 300 years of music. These “Four Seasons” are his way of reaching out to the past, creating a bridge between the world today, his childhood memories, and the original Vivaldi Four Seasons.

Isang Yun’s Königliches Thema bridges traditions both in space and time. The undercurrent here is literal: Bach’s Thema Regium from “The Musical Offering”, Musikalisches Opfer. This is the melody that was supposedly given to Bach by Frederick the Great in 1747 to test his skills at improvisation as he visited the court where his son Carl Philipp Emanuel was employed. The Thema Regium constitutes the foundation of this piece, omnipresent as the foundation of the devilish and at times dark Passacaglia, onto which Yun builds a virtuosic set of variations before returning to its simple and sublime original form at the end.

This dialogue between J.S. Bach and Isang Yun isn’t the only conversation taking place in Königliches Thema. The performer finds himself at a crossroads, moderating a discussion between Western and Eastern musical traditions. Yun blurs the line between the two to the point of making it disappear. But one can’t fully appreciate the composer’s musical language without understanding his complicated life. Born in 1917 in today’s South Korea, Isang Yun grew up under the colonial Japanese regime that occupied Korea from 1910 until 1945. He left to pursue his studies in Japan and after the war, returned to South Korea, becoming an activist for the reunification of Korea while teaching music. He moved to West Berlin in 1956, where, after further studies and a promising start to a career as a composer, his life took a dramatic turn: he and his wife were abducted by South Korean agents and forced to return to South Korea, where the couple was found guilty of sedition. Yun was sentenced to life imprisonment and his wife given a three year sentence. The West German government and the music world as a whole were appalled: how could a foreign government abduct such a respected musician from his residence in Berlin, force him to fly to South Korea and send him to prison for life? Numerous leading figures in music, including Karajan and Stravinsky, wrote letters to South Korean officials, but only after diplomatic pressure from the West German government were Isang Yun and his wife released and returned to Germany, where he became a professor at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin in 1970.

During the last 20 years of his life, he led the efforts to introduce new music from the West to the hermetic North Korea. His multiple visits to Pyongyang facilitated collaborations between musicians from the South and the participation of international musicians in North Korea’s annual Isang Yun Festival. His relationship with the South was muddied by the political realities of the time, and he was never able to return to his homeland. Since his death in 1995, Isang Yun has been recognized as a cornerstone of classical music in South Korea. The Tongyeong International Music Festival was established in his honour in 2002 and the government of South Korea finally acknowledged in 2006 the fabrication of the accusations that had originally sent him to prison.

Königliches Thema demonstrates that conflict between East and West in Yun’s life. As he himself mentioned in an interview with Bruce Duffie in 1987, “I’m a man living today, and within me is the Asia of the past combined with the Europe of today. That’s my world and my independent entity.” For Yun, his inspiration comes from the flow of music in the cosmos. He’s a mere“antenna” as he calls himself, able to draw from this endless source, dictated by his “deep-lying inner feelings.” There is no East or West for him, it’s all drawn from the same source. He was convinced, as he states, “of the unity of these two elements”. This cosmic flow of music is the foundation for Königliches Thema’s circular structure. The piece starts with a literal quote of Bach’sThema Regium and after seven variations with increasing intensity and virtuosity, Yun returns to the simplicity of the beginning. A reimagined version of Bach’s theme, up an octave and with some liberties in the expression, ends the piece in a dreamlike state of mind. The influence of the Western tradition is clear from the beginning, as Yun utilizes twelve-tone techniques to compose the variations. The first five notes of the theme constitute the core for the whole work: he transforms these pitches by inversion and transposition methods, highlighting the pitch class set 0-1-4 (B-C-E flat and G-A flat-B) as the structural and melodic foundation of the work. The original Theme is transposed throughout the running Passacaglia, with restatements starting on E flat and G, just like the opening C minor triad. The theme reappears in its original form in C for the dream like conclusion. Western compositional techniques are only used to highlight Yun’s roots in Taoist philosophy. “Stillness in motion, motion in stillness.” The structural symmetry of the work evokes the balance that is at the heart of entering “the Way.” As stated on the Tao Te Ching, cornerstone of Taoism, “Returning to the source is stillness. It is returning to one’s fate. Returning to one’s fate is eternal.”

I hope the listener will appreciate the beauty that Isang Yun is able to capture from these conversations that are happening at the same time, while the Thema Regium never lets go. Bach’s long shadow over the music of the past 300 years is ever present. From 1747 to 1970, East to West, Yun finds himself at the crossroads between space and time, old and new.

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998)

Suite in the Old Style for violin and piano

A knowledgeable music lover, when first listening to Schnittke’s Suite in the Old Style, might well be shocked. Anyone familiar with anything the man had written until that point would think they had mistakenly put on the wrong track. What had become of Shostakovich’s influence? How about Schnittke’s exploration of the twelve-tone system, such as in his first Violin Sonata? He had already started developing his unique polystylistic style with his Second Violin Sonata, Quasi una sonata, rooted in his unparalleled ability to imitate music from different eras. But this work marks his best effort to that date to lose himself in borrowed styles, shying away from any sort of atonality until the shocking chord of the concluding Pantomime.

Suite in the Old Style presents the listener with a very interesting combination of different aspects of this so-called “Old Style,” the Western tradition from Baroque onward and its interpretation by performers of the era in which the Suite was written. Born in Engels, Russia, he spent a part of his childhood in Vienna, where he first encountered the Germanic music tradition. After moving back to Russia and studying at the Moscow Conservatory, Schnittke started exploring different paths of musical expression through the 1960s while following his obsession to write for the violin. During this time, he sustained himself by writing soundtracks for movies and cartoons. In fact, the music from Suite in the Old Style is a combination of fragments from different Schnittke soundtracks to Russian films, including music written for Klimov’s dark film, Adventures of a Dentist. Shortly after this composition, the success of his First Symphony was followed by a long career full of fruitful relationships with some of the best string players of our time, such as Gidon Kremer and Mstislav Rostropovich. Schnittke, though at times at odds with the Soviet authorities and in frail health during his later years, has become one of the giants of Russian music for his avant-garde incisive style and his invaluable additions to the string and chamber repertoire.

As this recording was coming together, I had a choice to make: whether to record it with piano or harpsichord. Schnittke leaves this choice to the performers, forcing them to make an informed decision after close study of his keyboard writing. Music written specifically for harpsichord is usually conceived with that antique instrument’s limitations in mind: its meagre resonance, and a mechanism that doesn’t allow for dynamics in single notes, plucking the string the same way no matter how much the player presses on it. Composers get around these obvious limitations by writing a lot of dense chords and fast passages, overlapping notes while creating the sense that it is louder by adding more activity. But Schnittke doesn’t generally use any of those elements in writing the keyboard part of this Suite; one could say that the writing is austere, almost stingy. At times, his writing for the keyboard consists of no more than two single note lines, interacting with the violin line as three equal voices with interchanging roles. The textures created by Schnittke seem, in my opinion, better suited to the piano: playing with barely any pedal and maximum clarity, the pianist can highlight the simplicity in the language of each of the movements.

The most fascinating aspect of this work is how Schnittke’s compositional style is heavily influenced by the musical aesthetic of his own time: the writing represents a sort of time capsule, portraying what “Baroque style” meant to performers in the 1970s. The exaggerated gestures, verticality, and highlighting the sense of drama to the point of becoming ceremonial – all these very much defined the approach most violinists of the time applied to works like Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. When performing the Suite in the Old Style, one cannot help remembering Jascha Heifetz’s interpretation of Bach’s Chaconne, or thinking back to the two legendary recordings of Henryk Szeryng playing all six Sonatas and Partitas. The extended use of vibrato, highlighting the harmonies and the drama, combined with a strong articulated right hand, are some of the qualities that are characteristic to the Baroque playing of that era, qualities that Schnittke showcases throughout the piece.

This influence is specially noticeable in the cornerstone of the Suite in the Old Style: the A minor Fugue. The composer hammers the listener with repeated quarter notes and strong dynamics – blunt, square gestures that are exchanged among the three voices in a traditional fugal structure. The fugue’s martial character can be directly tied to its original purpose as part of the soundtrack for Klimov’s film Sport, Sport, Sport. A semi-fictional documentary “about the role and meaning of sport in a modern society,” Schnittke’s music highlights the brutality and competitiveness of sports in Soviet Russia. The philosophy of sport “as a continuation of war using peaceful means,” was not quite what Klimov had in mind. He saw this movie as a representation of sports as “mighty means to unite people, a formula of harmony.” Schnittke’s writing tells us otherwise.

Other movements throughout the Suite transport us to different places, such as the comfortable and peaceful Pastorale, which, with dotted rhythms, at times seems to take the listener for a leisurely stroll, or the quirky Ballet that follows, a miniature full of excitement that takes us to a fantasy land full of dancing creatures that are slightly too heavy and clumsy to dance gracefully.

The Menuett puts the performer in a conundrum: the music was written as part of the soundtrack for the Russian children’s cartoon The Butterfly, but it is probably the most sombre movement of the entire Suite. Its slow pace takes away most feelings we associate with childhood. Darkness takes over: minor harmonies, hemiolas appear between the bass line and the rest of the voices, and the almost constant and endless quarter note bass line dissipating into thin air with the C sharp picardy third, a characteristic Baroque ending.

After the ceremonial Fugue, the Suite ends with its most unique movement: The Pantomime. The music lives up to that name. It is extravagant and bizarre, taking us not just back to the Baroque, but to the ancient Pantomime of Roman times. That exaggerated style of dancing heavily influenced ballet masters during the 17th and 18th centuries, who sought to connect with the past and follow some of the principles of the Pantomime written down by Lucian in the second century AD. Schnittke reflects these bizarre qualities through strange melodies in a slow 3/4, in dance-like gestures that should be way too slow to work, and with the biggest surprise of the whole piece, a clashing minor second that appears out of left field, held by the violin for nine full bars before returning to the over-simplistic beginning, as though nothing had ever happened.

Suite in the Old Style is a strange but fascinating work, in which Schnittke seems not just to travel back to the 18th century, but also to take us back to 1972, showing us how much the meaning of the words “Old Style” has evolved in classical music over the past 50 years.

Salvador Brotons (b.1959)

Variacions sobre un tema barroc for solo violin

For me, Salvador Brotons’ Variations on a Baroque Theme serves as a roadmap back to my own personal musical origins. My relationship with Salvador dates to spring 2000. As a fearless nine year old kid wearing a light grey waistcoat and bow tie, I performed with an orchestra for the first time – Mozart’s Turkish A Major Violin Concerto, with the Balearic Islands Symphony Orchestra; four performances in two days, and Salvador on the podium. I still recall the excitement of getting on that stage and looking out at the audience. It was my time to share my innocent, almost naïve love for Mozart’s music with the 2000 students who came to the performances. The intensity coming from the podium was exhilarating. This very tall and energetic figure leading the orchestra, giving me the opportunity of playing with a great orchestra at such a young age.

The friendship stuck over the years, from Sibelius together with the Vancouver Symphony, to programming his solo violin work Et in Terra Pax in recital programmes over the years. In recording this album, I wanted to include a work that carried the listener back to my first steps as a musician, sharing the stage with Salvador in the island of Mallorca.

The new work by Brotons doesn’t just connect to our personal relationship, but to our shared roots, each growing up on the shore of the Mediterranean. Born in Barcelona into a family of musicians, Salvador Brotons has developed a multifaceted career as a conductor, flutist and award-winning composer. With an opus extending over 140 works, his music is inspired by the Catalan and Mediterranean culture. This work brings Brotons back to the eight years spent in Mallorca as music director of the Balearic Islands Symphony Orchestra. It recalls one of the best-known songs by the Mallorcan composer Antoni Lliteres, from his zarzuela Acis Y Galatea, written in 1708. In the song, Galatea sings about the goldfinch’s lively movements, speaking of love and pain in a bittersweet and playful manner.

Si de rama en rama si de flor en flor Y vas saltando, bullendo y cantando dichoso quien ama las ansias de amor. Advierte que aprisa es llanto la risa Y es gusto el dolor. Ay!

(“From branch to branch, from flower to flower. You jump, bubbly singing how blessed is the one who embraces love’s anxieties. You warn us how quick laugh turns to cry; and how pain is enjoyable. Ay!”)

Brotons develops Lliteres’s theme in a deliberate manner. One can discern his obsession with the original melody; in fact, he seems reluctant to move away from the theme’s uncomplicated and smooth writing. Brotons puts a lot of effort into making sure he doesn’t venture too far too early into his own sound world, with the full array of luminous colours and angular gestures that become so characteristic of his opus.

The challenge when performing any theme and variations is to maintain the spirit of the original theme while exploring the transformation of its musical language into new modes of expression with each variation. In this case, Brotons establishes a balance between old and new by slowly moving away from techniques commonly associated with the Baroque era. After the opening variations are sculpted in consonance with Lliteres’s simpler style, the all-pizzicati fourth variation allows for a fully modern approach, here percussive and intense. Brotons then retreats immediately, back to the sounds of the Baroque, his fifth variation paying homage to the solo violin tradition of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas, just as he did in his earlier solo violin piece, Et in Terra Pax.

Brotons puts everything he has into the last variation. His outgoing and intense personality unfurls in this music, as he unapologetically pushes his performer to the limit. He has discarded all the layers that veiled his writing up until this point, showing us his true character. Put simply, Salvador Brotons’ constant motor brings music to life.

© Francisco Fullana

Francisco Fullana

Spanish violinist Francisco Fullana has received international praise as a “rising star” (BBC Music Magazine), an “amazing talent” (Gustavo Dudamel) and “a paragon of delicacy” (San Francisco’s Classical Voice). His 2016 recital debut at Carnegie Hall was noted for his “joy and playfulness in collaboration; it was perfection” (New York Classical Review).

A native of the Spanish Balearic island of Mallorca, Fullana is making a name for himself as both a performer and as a leader of innovative educational institutions. His active performing schedule has included a Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with the Bayerische Philharmonie, under the baton of the late Sir Colin Davis, the Sibelius Concerto with the Münchner Rundfunkorchester,and a Brahms Concerto led by Gustavo Dudamel at Venezuela’s Simon Bolivar Hall. He has performed as a soloist with the Vancouver, Pacific, Alabama, Maryland, Madrid and Hof Symphonies and the Spanish Radio Television Orchestra, while collaborating with such noted conductors as Davis, Dudamel, and also Alondra de la Parra, Christoph Poppen, Jeannette Sorrell, and Josh Weilerstein.

Francisco has taken part in the Marlboro Music Festival and “Musicians from Marlboro” tours. He has joined in prominent chamber series including the

Music@Menlo, the Da Camera Society, Perlman Music Program, and Yellow Barn, alongside members of the Guarneri, Juilliard, Pacifica, Takacs and Cleveland Quartets, while performing alongside such renowned artists as Viviane Hagner, Nobuko Imai, Charles Neidich and Mitsuko Uchida, among many others.

In 2017 Fullana had debut performances with the Castilla y Leon Symphony Orchestra, Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, in addition to first engagements in the U.S., Europe and Asia. Among the many chamber music engagements on his upcoming schedule, he has been invited to join the prestigious roster of Lincoln Center’s Chamber Music Society Two, starting in 2018.

Born into a family of educators, Francisco first studied with Bernat Pomar in his hometown of Palma de Mallorca, later graduating from the Royal Conservatory of Madrid, where he matriculated under the tutelage of Manuel Guillén. He is a graduate of The Juilliard School, where he received bachelor’s and master’s degrees, studying with Donald Weilerstein and Masao Kawasaki, and is also an Artist Diploma graduate from the USC Thornton School of Music, where he worked with the renowned violinist Midori.

Fullana was honoured in 2015 with the Pro Musicis International Award, the same year also finding him awarded First Prize in the Munetsugu Angel Violin Competition in Japan, along with all four special prizes including the Audience and Orchestra awards. He won First Prize in the 2014 Johannes Brahms International Violin Competition in Austria, while his other awards include First Prizes at the Julio Cardona International Violin Competition and the Pablo Sarasate Competition.

Francisco Fullana has also become a committed innovator, leading new institutions of musical education for young people. He is a co-founder of San Antonio’s Classical Music Summer Institute, where he currently serves as Chamber Music Director. He also created the Fortissimo Youth Initiative, a series of baroque and classical music seminars and performances with youth orchestras, which aims to explore and deepen young musicians’ understanding of 18th century music. The seminars are deeply immersive, thrusting youngsters into the sonic world of a single composer, while inspiring them to channel their overwhelming energy in the service of vibrant older styles of musical expression. The results can be galvanic, and Fullana continues to build on these educational models.

Mr. Fullana currently performs on the 1735 “Mary Portman” ex-Kreisler Guarneri del Gesù violin, kindly on loan from Clement and Karen Arrison through the Stradivari Society of Chicago.

www.franciscofullana.com

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra

The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra gives over 130 concerts each year in Birmingham, throughout the UK, and around the world, playing music that ranges from classics to contemporary, to film music and more. The orchestra, steeped in commitment to its home city and the Midlands, dates to a first concert in 1920, conducted by Sir Edward Elgar. Ever since, through war, recessions, social change and civic renewal, the CBSO has served the city of Birmingham. Under principal conductors including Adrian Boult, George Weldon, Andrzej Panufnik and Louis Frémaux, the CBSO won an artistic reputation that spread far beyond the Midlands. But it was when it discovered the young British conductor Simon Rattle in 1980 that the CBSO became internationally famous – and showed how the arts can help give a new sense of direction to a whole city.

Rattle’s successors Sakari Oramo (1998-2008), Andris Nelsons (2008-2015), and the current leader, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, have helped cement that global reputation, and continued to build on the CBSO’s tradition. As the only professional symphony orchestra in its region, the orchestra has travelled to Japan and the United Arab Emirates in recent seasons, and in December 2016 the CBSO made its debut tour of China. Its recordings continue to win acclaim. In 2008, the CBSO’s recording of Saint-Saëns’ complete piano concertos was named the best classical recording of the last 30 years by Gramophone.

Carlos Izcaray

The Venezuelan born Carlos Izcaray is Music Director of the Alabama Symphony Orchestra and of the American Youth Symphony. As a widely-praised conductor, he has led performances of ensembles around the world, including the St. Louis, North Carolina and Grand Rapids Symphonies, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, Orquesta Sinfónica Venezuela, Orquesta Filarmónica de Bogotá, the Bangkok Symphony Orchestra and Sweden’s Malmö Symfoniorkester, among many others. His operatic work includes performances with the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, Opera Omaha, and in particular the Wexford Festival Opera (Ireland), where he has led several productions, in 2010 conducting the 19th century tragedia lirica Virginia that won Best Opera prize at the Irish Theatre Awards. He is also a distinguished cellist.

Born in Caracas, Izcaray began studies in conducting in his teens. He is an alumnus of the Interlochen Arts Academy, the New World School of the Arts, and Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. He won top prizes at the 2007 Aspen Music Festival and at the 2008 Toscanini International Conducting Competition. He has taught in his nation’s renowned El Sistema, while working with educational institutions throughout the Americas and British Isles.

David Fung

Described as “stylish and articulate” in the New York Times and having “superstar qualities” by Le Libre, pianist David Fung regularly appears with the world’s premier ensembles, including the Cleveland Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, the National Orchestra of Belgium, National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra, New Japan Philharmonic Orchestra, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, San Diego Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, and Australia’s Sydney Symphony Orchestras. David Fung’s 2016 debut at Cleveland’s Blossom Music Festival elicited wide acclaim, being noted as “everything you could wish for” (Cleveland Classical).

David Fung has performed at the Kennedy Center, Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, Wigmore Hall, the Zürich Tonhalle, the Gewandhaus, the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, the Louvre, and numerous major venues in Asia including the Beijing Concert Hall, National Concert Hall in Taiwan, Guangzhou Opera House, and the Tianjin Grand Theatre. He is a frequent guest of major festivals including Aspen, Caramoor, Ravinia, Sun Valley, Hong Kong Arts Festival, and the Edinburgh International Festival, where the Edinburgh Guide described him as being “impossibly virtuosic, prodigiously talented … and who probably does ten more impossible things daily before breakfast.”

The first piano graduate of the prestigious Colburn Conservatory in Los Angeles, David Fung also studied at the Hannover Hochschule für Musik and the Yale School of Music. He was a winner in the Queen Elisabeth International Music Competition in Brussels and the Arthur Rubinstein Piano International Masters Competition in Tel Aviv, where he was further distinguished by the Chamber Music and Mozart Prizes.