Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Yu Kosuge, piano

Four Elements Volume I: Water

Release Date: 16th November 2018

ORC100092

Four Elements: Water

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

1 Songs Without Words, Op.30 No.6 in F sharp minor

(Venetian Gondola Song No.2) 3.37

Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924)

2 Barcarolle No.5 in F sharp minor, Op.66 5.37

Felix Mendelssohn

3 Songs Without Words, Op.62 No.5 in A minor

(Venetian Gondola Song No.3) 2.58

Gabriel Fauré

4 Barcarolle No.10 in A minor, Op.104 No.2 3.00

Felix Mendelssohn

5 Songs Without Words, Op.19 No.6 in G minor

(Venetian Gondola Song No.1) 2.10

Gabriel Fauré

6 Barcarolle No.11, Op.105 in G minor 4.23

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

7 Jeux d’eau 5.13

Dai Fujikura (b.1977)

8 Waves 3.03

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849)

9 Barcarolle in F sharp major, Op.60 9.05

Tōru Takemitsu (1930–1996)

10 Rain Tree Sketch I 4.23

Tōru Takemitsu

11 Rain Tree Sketch II: In memoriam Olivier Messiaen 3.55

Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

12 Les jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este from

“Années de pèlerinage III” S.163-4 8.02

Franz Liszt

13 Ballade No. 2 in B minor, S171 15.21

Richard Wagner (1811–1883) (transcribed Liszt)

14 Isoldes Liebestod from “Tristan und Isolde” 7.35

Total time 78.26

Yu Kosuge, piano

The Four Elements:

Water, Fire, Air, Earth

“The four elements are unified through Love (Philia) into one cosmos, andseparated by Strife (Neikos). They are the roots of everything: past, present and future.”

Empedocles (c.483 – c.423 BC)

“Our daily life has become routinely convenient in today’s society. We can get in touch with others wherever we are, and can travel anywhere easily. However, we could ask ourselves if our way of life is natural: are the depth of our relationships with one another, and our way of sharing time getting closer to the essence of humanity, or are we moving away from it? What is the meaning of our life nowadays?

Through “Four Elements”, those most essential to our universe, I wish to face these questions with my audience. Passed on by many philosophers from diverse eras since before Christ, the four-element theory has been interpreted differently in each cultural, religious or national background, giving birth to numerous myths and thoughts. Musically speaking, the four elements inspired composers’ imaginations to create not only images or impressions but also works with profound metaphoric messages based on literature or philosophy. These abundant pieces differ widely from each other; from clear, subtle or pure to cruel, passionate or demonic. Even if belonging to a fantasy or imaginary world, their poetry and emotions are always connected with our reality. I would like to visit these works born by nature to explore the origin of this wonderful world and the beauty of our life itself.”

Yu Kosuge

Four Elements: Water

On the project “Four Elements”

For six years from 2010, Yu Kosuge, one of the most critically acclaimed Japanese pianists, performed the complete Beethoven piano sonatas as a cycle in Tokyo and Osaka. Alongside this she recorded all 32 sonatas on five separate albums (Sony), of which Vol. 5 “Botschaft” (Op.13, 26, 54, 57, 109, 110 and 111) received the 54th Japan Record Academy Award for Best Instrumental Album in 2016. Subsequently, she launched a new Beethoven project “Beethoven MO-DE,” in which she will perform all existing compositions by Beethoven with piano, heading towards Beethoven’s 250th anniversary in 2020.

Thus, Kosuge has devoted herself to exploring Beethoven’s music all the more, but at the same time, her strong artistic desire has brought forth another project “Four Elements,” which is actually an outgrowth of the Beethoven sonata cycle.

“With the Beethoven cycle, my goal was to think together with the audience, especially with young people, about existential questions like “What is humanity, where are we from?” or “What does life mean?” This time, with the “Four Elements”, I want to dig deeper into those questions, for these elements are the basis of humanity. When you understand that Shakespeare’s plays, read ardently by Beethoven, refer to Greek mythology, or that Beethoven himself composed some works based on the Prometheus myth, you would know that an artist who is searching for human nature would surely look to Greek mythology or philosophy at some point. I myself was deeply impressed by ancient Greek philosophy while I was speculating about the answers to those questions.”

As seen in her preface to this album, Kosuge has been inspired by the Greek philosopher Empedocles, who, through his concept of unification (Love) and separation (Strife) of the classical four elements (water, fire, wind and earth), attempted to settle a controversy between two opposite theories: Parmenides’ idea of unchanging permanence (“nothing comes from nothing”) and Heraclitus’ idea of eternal change (“everything flows”). The pieces she chose for this album consist of different composers according to the period and region but they share the universal question of all ages: what is human nature? In a way, Kosuge’s programming concept for the “Four Elements” reflects Empedocles’ thoughts.

In her programme “Four Elements: Water”, Kosuge states her intention as follows:

“Water is considered the most essential element for living by any culture. In fact, 90 percent of the adult human body consists of water, and for Christians, water symbolizes the origin of existence. It is considered to be pure and calm, but on the other hand, causes chaos and floods, a source of destruction (Noah’s Flood)! In a word, this element brings about both vitality and death. Also, the flow of water is a metaphor for “eternity”. I put this program together thinking of this “flow” from past to future, from the real world to the unknown, and the power of water itself.”

After her tour of “Four Elements: Water” in 2017, Kosuge recorded this programme, i.e., the present album, but added Dai Fujikura’s new piece Waves (2018) which she premiered at the Wigmore Hall in February 2018.

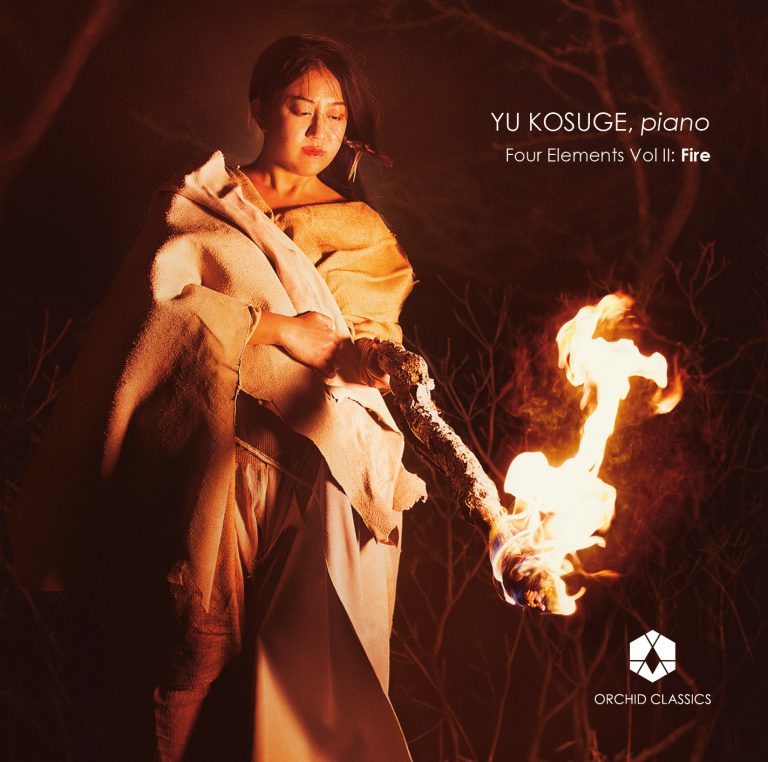

Hereafter, she is scheduled to make recital tours of “Fire” in autumn 2018,

“Wind” in autumn 2019 and “Earth” in autumn 2020.

The Tale of Water told through Barcarolles

The tale of water starts with Venetian barcarolles (boat songs).

During his first visit to this “City of Water” Mendelssohn wrote about his impression of riding on a gondola in his letter dated October 1830. “At this moment the gondoliers are shouting to each other, and the lights are reflected in the depths of the waters. One is playing a guitar, and singing to it. It is a charming night”.

After this experience he composed three pieces entitled “Venetian Boat Song” which he subsequently included in “Songs Without Words” (Lieder ohne Worte). These three works are considered the first-ever solo piano pieces to depict Venetian barcarolles, with fluid rhythm in six-eight time.

“In all three barcarolles you can imagine the exact scenery the composer describes in his letter. The melody heard in No.2 (Op.30/6) carries a romantic atmosphere, while the beginning of No.3 (Op.62/5) reminds me of “echoing” yells by gondoliers. In No.1 (Op.19/6), in a typical manner, with his floating after-beat you can imagine the gondoliers rowing. I think the triple meter in western music, such as the waltz, is connected to the tradition and daily life of people living there.”

In 1891, almost 60 years after Mendelssohn’s visit, Fauré travelled to Venice for the first time, though six years earlier he had started composing a series of pieces entitled “Barcarolle” (he wrote a total of 13 during his lifetime). Here, Kosuge selects Barcarolle No.5 in F sharp minor, No.10 in A minor and No.11 in G minor, all of which were composed after the composer’s visit to Venice, and contrasts Fauré with Mendelssohn by making them a pair in the same key, clarifying differences between their styles.

“Unlike the simplicity of Mendelssohn’s boat songs, Fauré completely transformed this genre one step further, even if you do still hear the “rowing” rhythm. The importance of harmony, bass lines and use of daring modulations and Gregorian modes are typical to Fauré’s music. Among the three, No.10 and No.11 are written in a simple style which is characteristic of late Fauré. The influence of Bach is also present. The more complex style of No.5 shows Faure’s experimental attitude of the time, both in its chromaticism and harmonic instability. The florid, glittering colours of this music make you think of his song cycle “La bonne chanson”.

Chopin, unlike Mendelssohn and Fauré, never visited Venice, but widened the potential of the “Barcarolle” genre in a different way. His Barcarolle in F sharp major, with its graceful ostinato in twelve-eight time, evokes the heave of a mighty ocean.

“Here, with this grandness, the gondola could be pulling out into the ocean. I think this piece of late Chopin is one of his masterworks. How it slowly builds up to the incredible harmonies in the climax is just marvellous, you feel pain, joy and nostalgia all at the same time”

“Sketches” and “Metaphors” of Water

Chopin allegedly had his own students play Mendelssohn’s “Songs without Words”. Liszt devoted himself to performing Chopin’s pieces in his recitals, made a piano transcription of Wagner’s overture to “Tannhäuser”, and conducted the world premiere of “Lohengrin”, for the sake of promoting their music. Fauré went abroad many times to see Wagner’s operas, and Ravel dedicated his “Jeux d’eau” to his mentor, Fauré. In addition, Takemitsu composed “Rain Tree Sketch II” in memory of Olivier Messiaen, who was heavily inspired by Ravel. We notice all these composers selected by Kosuge for this album transcend time and space.

“After his visit to Bayreuth, Fauré composed “Souvenirs de Bayreuth” in collaboration with his friend André Messager. This piece for four hands is, in a way, a parody, but tells us also how Fauré knew Wagner and how deeply interested he was in his music. Even in his “Barcarolle” No.5 I hear some influence.”

On his manuscript for Jeux d’eau, Ravel wrote an epigraph “Dieu fluvial riant de l’eau qui le chatouille” (River god laughing at the water tickling him), a quote from Henri de Régnier’s poem “Fête d’eau” (Water Feast). This poem is certainly about Latona’s Fountain in the Gardens of Versailles (“Jeux d’eau” could be translated “fountain”). However, Ravel’s music written in sonata form doesn’t limit its expressions to pictorial depiction, which is classified in so called “Impressionism”.

“For me, the accelerando passage (during the development) is not just the fountain reaching the biggest climax, it is the outbursts of the innermost passion retained until then. I think in this youthful piece, Ravel’s romantic aspect comes to the surface.”

This is also true for Liszt’s Les jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este. At a glance, the composer seems to depict numerous fountains (consisting of 500 large and small fountains) in his beloved gardens of Villa d’Este. But when the music modulates from F major to D major, he moves away from virtuosity; instead, a more inner expression arises from the depth of the music. In this section, Liszt inscribes on his manuscript a Latin translation of Jesus’ words from the New Testament: “…but whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a fountain of water welling up to eternal life.” (John 4:14)

“Indeed the religious outlook of late Liszt exudes here. I believe he acknowledges how human beings are alive, because water equals eternal life, which also shows how personal and intimate this music is, without any showmanship.”

Takemitsu’s Rain Tree Sketch I and Rain Tree Sketch II: In memoriam Olivier Messiaen contain this conversion of musical depiction of water into a metaphor of life itself. Both pieces were inspired by “The Clever Rain Tree (Atama no ii “Ame no ki”)”, a short novel by Kenzaburo Oe, a close friend of Takemitsu. In the novel, Oe describes an enormous Bodhi Tree (called “Rain Tree” in the story) with countless leaves retaining raindrops on the underside. The tree, even after a shower passes by, drips water like falling rain. Having these pieces’ scores on her music stand since childhood, Kosuge feels the existence of humanity and life itself in both pieces.

“As a child, when I was playing the moment the right and left hands cross in “Rain Tree Sketch”, I recalled the Buddhist bell ringing during my great aunt’s funeral. Then, when I got older and read Oe’s story, I was surprised that “Rain Tree” is the Bodhi Tree under which Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) gained enlightenment. In the novel, “Rain Tree” is also described as a symbolic tree carrying varied ethnic histories. That’s why the falling water drops of the tree seem to me not just water but tears that embrace various human emotions. But maybe my personal experience inspires this interpretation….”

It was the novelist and bookbinding designer Osamu Tsukasa, also a friend of Takemitsu, who was in charge of the binding of “The Clever Rain Tree”. Tsukasa’s autobiographical novel “Watercolour (Sui-Sai)” is based on an anecdote of the premiere of Takemitsu’s piece “Rain Tree” for percussion trio (his Rain Tree Sketch is related to this piece). Tsukasa quotes the composer’s words: “Have you ever watched Tarkovsky’s “Solaris”? There is a magical power in that film. Water is magical, too. And I hear music in Tarkovsky’s films.” Takemitsu loved Tarkovsky’s films, in which water appears in various metaphorical states such as the rain or sea, seeming itself to be living, especially in “Solaris” focusing on human memory. Taking this into consideration, it is possible that Takemitsu was aware of the magical power of water writing these two Rain Tree Sketches. Listening to them, like watching Tarkovsky’s films, with water as mere scenery metamorphosing into metaphors, wouldn’t be against the composer’s intention.

Love, Death and Transfiguration on the Ocean

Kosuge concludes “Four Elements: Water” with two Romantic pieces surrounding the related-to-water legends about love and death of the lovers, and their transfiguration.

“When I was in high school in Germany I had classes in Latin and classical Greek, and it was usual in our class to translate ancient Greek myths. It was difficult and I had a really hard time, but this experience made me deeply interested in Greek mythology. I always liked stories, and I love to watch movies as they tell all kinds of stories. I don’t think the ancient myths are more difficult to understand than modern novels, movies or animation.”

One theory is that Liszt’s Ballade No.2 was influenced by the Greek myth “Hero and Leander”. Claudio Arrau, the legendary Chilean pianist, also suggests that Liszt got his inspiration from this myth. The young Leander swims every night across the strait to see his beloved Hero. One night, Leander got tossed by raging waves and drowned, and the despaired Hero throws herself into the sea.

“From the beginning the first theme depicting stormy waves foreshadows the final tragedy and the lyrical theme embodies the couple’s pure love… If you actually read the myth, you can imagine quite plainly the story’s scenes while listening to Liszt’s music. At the end, when it turns into B major, it seems that there is a metamorphosis, suggestive of the dead lovers’ souls raising to the skies. We could probably say that such a metamorphosis is an element common to “Isoldes Liebestod (Isolde’s Love Death)”.

Liszt made a transcription of Isoldes Liebestod, the last piece of Wagner’s masterpiece “Tristan and Isolde”, which is based on the tragic love story of the knight Tristan and the princess Isolde. They drink a love potion on board a ship, making them fall madly in love. The lovers are torn from each other due to their allegiance, and in the final act, when Isolde arrives on a ship at Tristan’s side, he loses his life in her arms.

“If you read Wagner’s libretto, you find several moments where sensual images and water images overlap, e.g., “In dem wogenden Schwall” (In the billowing torrent). I think Isolde doesn’t merely sing about the love between two people, but comments on human love itself. The story of this opera tells us that the morals of society and human love are two different things. While restrictions in the 19th century were much greater than today, Wagner sends us a great message of freedom and love of humanity.”

Interestingly enough, Wagner composed the second act of “Tristan and Isolde” hearing gondoliers singing during his stay in Venice from 1858 to 1859. This tale of water which began with Venetian barcarolles, heads toward “Isoldes Liebestod”, as if on Charon’s boat, leading human souls to eternity.

© Hidekuni Maejima (Sound & Visual Writer)

On Dai Fujikura’s “Waves”

Dai Fujikura wrote this piano piece as a sketch for another work. He was hoping this material would be a part of the Piano Concerto No. 3 which he has written for me, but eventually it didn’t get included. It is now a beautiful independent piano piece and I’m happy to include it in this recording. I have always admired Dai’s harmonies and lyric sense, which stirs my imagination.

Dai comments:

“Waves has two contrasting sections. The harmony of the first section is gently and perpetually twisted in a lyrical fashion (perhaps like the spiral shape of DNA) and the second section is quite rhythmic, carrying a similar harmonic sense.”

Even though not directly connected to water, since there are many depictions of waves in this recording, I thought I can show another side of waves with this piece. In the first section I imagine different shapes of waves forming far away in the cosmos, and in the second section the staccato notes and accents in piano remind me of pointillism. With all these points together I see many kinds of waves moving around, with the rhythm constantly pulsing.

© Yu Kosuge

Yu Kosuge

With her superlative technique, sensitivity of touch, and profound understanding of the music she plays, Yu Kosuge has become one of the world’s most noted pianists of her generation.

She has appeared at leading venues in Berlin, Hamburg, Köln, Munich, Vienna, Salzburg, London, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Zurich, St. Petersburg, Tokyo, Washington and New York. She has been invited to festivals across Europe including Rheingau, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Salzburger Festspiele, Mozartwoche Salzburg and La Roque d’Anthéron Piano Festival.

As well as performances with all the major Japanese orchestras, Yu Kosuge has worked with leading European orchestras including the NDR Symphony Orchestra, NDR Radiophilharmonie, Berliner Symphoniker, Radio-Sinfonie Orchester Frankfurt, Camerata Salzburg, St Petersburg Symphony, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and the BBC Symphony Orchestra. She has performed with conductors of the stature of Seiji Ozawa, Philippe Herreweghe, Sakari Oramo, Yutaka Sado, Osmo Vänskä and Vasili Petrenko.

In September 2009 Sony released Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No.1 with the Mito Chamber Orchestra and Seiji Ozawa. Yu’s other recordings include Liszt’s 12 Études d´exécution transcendante and Mozart’s Piano Concertos Nos.20 and 22. Over the last few years Yu recorded all 32 Beethoven Sonatas. The boxed set was released in the autumn of 2016. In the autumn of 2018 Orchid Classics released the first of four CDs, ‘Water’, as part of her ‘Four Elements’ cycle.

Yu Kosuge is currently living in Berlin.

www.yu-kosuge.com