Artist Led, Creatively Driven

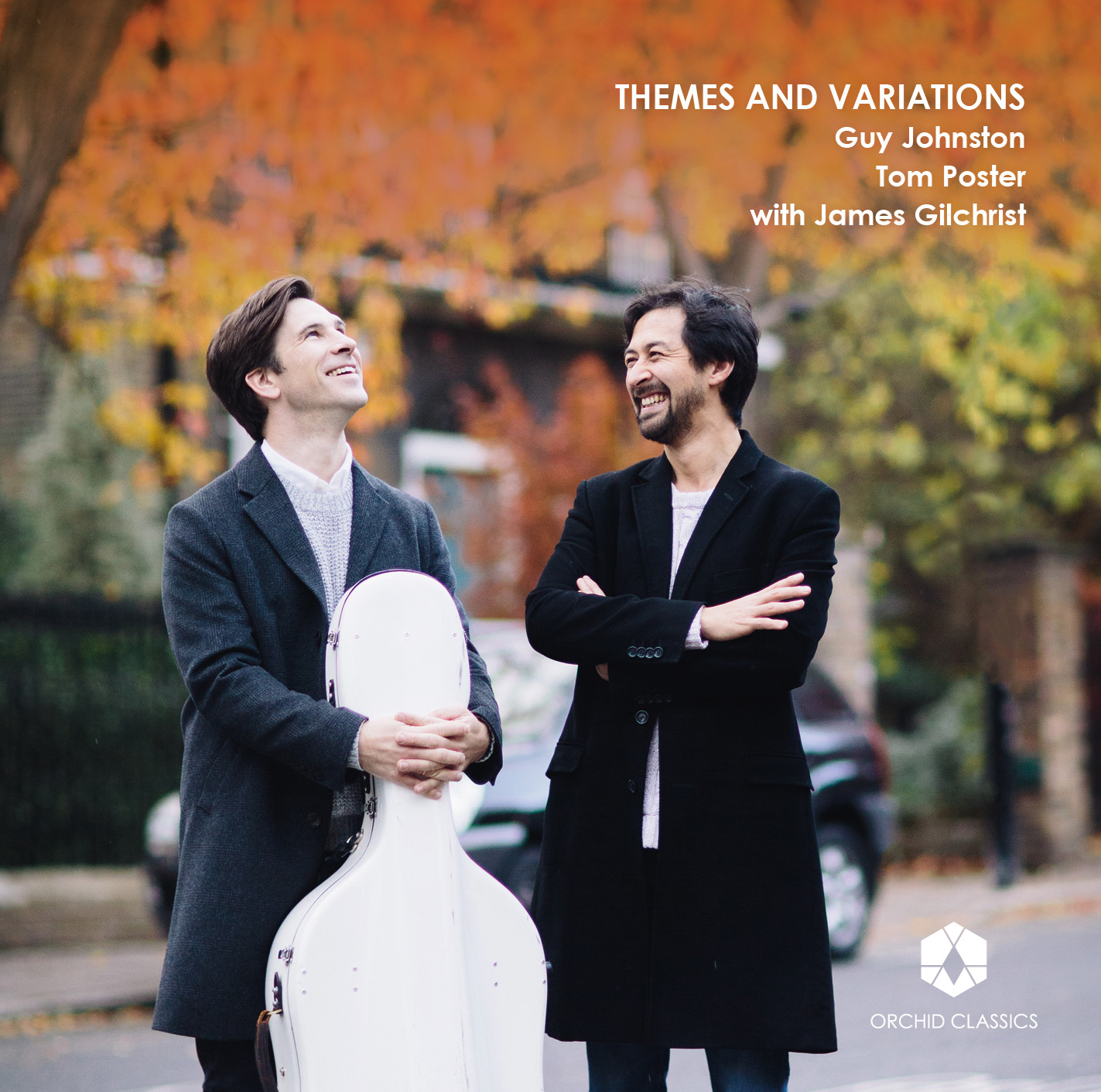

Themes and Variations

Guy Johnston, cello

Tom Poster, piano

James Gilchrist, tenor

Release Date: 1st March 2019

ORC100095

THEMES AND VARIATIONS

1 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827)

Variations on ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’

from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, WoO46 9.24

2 Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856)

Adagio and Allegro, Op.70 8.52

3 Gabriel Fauré (1845 – 1924)

Romance, Op.69 3.42

4 Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847)

Variations concertantes, Op.17 8.24

5 Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828)

Auf dem Strom, D943* 8.52

6 Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849)

Introduction and Polonaise brillante, Op.3 9.03

7 Sergei Rachmaninov (1873 – 1943)

Prelude, Op.2 No.1 3.18

8 Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959)

Variations on a Theme of Rossini, H290 7.31

9 James MacMillan (b.1959)

Kiss on Wood 6.57

10 Sergei Rachmaninov

Vocalise, Op.34 No.14 5.44

11 Camille Saint-Saëns (1835 – 1921)

The Swan (from The Carnival of the Animals) 2.36

Total time 74.31

Guy Johnston, cello

Tom Poster, piano

* with James Gilchrist, tenor

THEMES AND VARIATIONS

It recently occurred to us that we’ve now been playing together for half our lives. We first met in the final of the BBC Young Musician Competition 2000 at the age of 19, read through some sonatas together later that year on a tour of the Middle East, and have since shared a stage in concert halls and festivals all over the world. We’ve covered a vast amount of duo repertoire along the way, as well as expanding into larger formations (most significantly the Aronowitz Ensemble), but inevitably there are certain pieces we’ve become especially attached to, and which have seemed particularly significant for us on our journeys through life.

So this album is really a celebration of a long-standing chamber music partnership and a deep and enduring friendship. We’ve called the album ‘Themes and Variations’: although only three of the eleven works are explicitly in variation form, the title seemed in a broader sense to encapsulate the recurring themes and variations of our lives as we’ve navigated our way from late-teenage years to something occasionally resembling responsible adulthood.

A few words on the music we’ve chosen:

Beethoven professed The Magic Flute to be his favourite of Mozart’s operas, and ten years after its 1791 premiere, he produced this glorious set of Variations on ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’, a duet sung by Pamina and Papageno – two characters not themselves romantically involved – in praise of love. Here the piano and cello immediately take on the roles of soprano and baritone respectively in their sharing of the theme, before journeying together in true operatic style through comic exchanges, dramatic outbursts and lyrical melodies. We have opened many recitals with this piece over the years, enjoying its generous spirit and its celebration of the companionable nature of cello and piano.

At one of our earliest recitals together, Tom was just about to launch flamboyantly into the rich opening chord of the Beethoven Variations, when he looked round at Guy, who was poised for the quiet, slow up-bow which begins Schumann’s Adagio and Allegro. (We have since learned the importance of checking we both know the programme order in advance of the performance!) This heartbreakingly beautiful Schumann work, composed in 1849, might well be the piece we have played most together. The first of two pieces on this disc ‘borrowed’ from the horn repertoire (here with the composer’s permission), the tender love-duet of its opening Adagio, which Schumann initially entitled Romance, makes a perfect foil for the ecstatic exuberance of the Allegro which follows. Clara Schumann described it as “a magnificent piece, fresh and passionate, and exactly what I like”.

An actual Romance next, by Fauré, a composer whose importance to the cello and piano repertoire cannot be overstated. While Fauré’s two cello sonatas are masterpieces of rare emotional depth, his miniatures are among the most enchanting of salon pieces. This meditative Romance, which started life as a piece for cello and organ, features exquisitely subtle shifts of harmony which could belong to no other composer, and it was Fauré himself who played the piano part at this version’s premiere in 1894.

The second of three sets of variations on this album, Mendelssohn’s Variations concertantes differs from the others in being written on an original theme, rather than borrowing from an earlier composer. Written in 1829, when Mendelssohn was twenty, to play with his cellist brother Paul, the variations show the classical influence of Mozart and Beethoven but eventually burst out into a more overtly Romantic display of passion and bravura. A performance of this piece at the Hay Festival a few years back gave rise to one of our favourite recital stories. We opened the concert with this work, and all went smoothly until the final variation, at which point – as Tom began the tranquil reprise of the theme – the piano suddenly shot a few feet across the floor. It transpired that nobody had thought to tighten the brakes, and as Tom leapt off his stool to chase the piano while continuing to play, the page-turner valiantly leapt down, caught hold of the piano leg and applied the brakes. Meanwhile, Guy calmly held his sustained note, wondering what on earth was going on behind him. To add to the excitement, the whole recital was being broadcast live on BBC Radio 3, whose listeners were presumably none the wiser about the extraordinary antics happening on stage!

As Beethoven paid homage to Mozart in his variations, Schubert composed Auf dem Strom as a tribute to Beethoven, the composer he most revered, and at whose funeral he had been a pallbearer. Premiered on March 26th 1828, at the only public concert during Schubert’s lifetime devoted entirely to his music, Schubert sets a poem by Rellstab – which Beethoven had intended to set before he died – in which a journey to a faraway place becomes a metaphor for death and passage into the next world. Schubert’s choice of text seems both prescient and poignant: at the time of this setting, he had only eight months to live. Like the Schumann heard earlier on this disc, the cello part – which sings its own melody between each of the tenor’s strophes – was originally intended for horn, but seems equally idiomatic on the cello. We are so delighted that James Gilchrist, a regular and much-admired collaborator of ours, agreed to join us for this elegiac masterpiece.

Only one year separates this late work of Schubert from the extrovert world of Chopin’s early Polonaise brillante, written in 1829, the same year as the Mendelssohn Variations. Chopin self-deprecatingly declared this polonaise ‘nothing more than a brilliant drawing-room piece suitable for the ladies’, but the expressive introduction which he added a year later shows great lyrical beauty, while the polonaise itself has irresistible charm, energy, and a staggering number of notes-per-minute for the pianist in particular. This has proved one of our most enduringly beloved concert pieces, stretching right back to our earliest concerts together, one of them a live (and therefore slightly terrifying) broadcast on BBC TV in our undergraduate days.

Like Chopin, Rachmaninov’s music mostly casts the spotlight on his own instrument, the piano, but the small handful of chamber works which each of these great pianist-composers produced reveals in both cases a particular fondness for the cello. Rachmaninov’s early Prelude, probably written in 1891 when the composer was 18, is a reworking of a solo piano piece whose sweet lyricism seems particularly suited to the cello.

Like Beethoven, Martinů chose a theme of operatic inspiration for his virtuosic Variations on a Theme of Rossini, though here the theme’s origin is considerably more confusing and the title something of a misnomer. Most sources state that the theme is taken from Rossini’s opera Moses in Egypt, a factoid which resulted in Tom spending many puzzled moments trying and failing to find the theme in scores and recordings of the Rossini. In fact the theme Martinů uses was written by another Italian composer – Paganini – for his Variations on One String. In Paganini’s work, Rossini’s Moses is quoted only in its introduction, which is never actually used by Martinů; this is why the listener will not hear any notes actually written by Rossini in Martinů’s work. Written in 1942 for the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, this was one of Martinů’s first works completed after he fled Paris for the US in the face of the Nazi invasion. Its wit and light-hearted brilliance belie the troubled times in which it was written, though a darker shadow falls across the wistful third variation.

James MacMillan’s Kiss on Wood is a paraphrase on the Good Friday versicle, ‘Ecce lignum crucis’; it was originally written for violin and piano in 1993 and is, in the composer’s own words, a “short, static and serene meditation”. MacMillan adds that “the music and title are devotional in intent but can equally represent a gesture of love on the wooden instruments making this music”. Guy had the pleasure of working with James MacMillan on the orchestral version of this piece, and recalls his reference to the historical practice of keening – a wailing lament for the dead performed at Celtic funerals – whose echoes are heard in the cello’s haunting melodic line.

And out of the silence into which Kiss on Wood dissolves, a pair of reflective encores: firstly Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, originally a wordless song, spins – like the MacMillan – a long-breathed line of aching beauty, though here there is an unmistakably Russian flavour. Finally, it seems fitting that Saint-Saëns’ The Swan (the only movement of The Carnival of the Animals he permitted to be published in his lifetime) should close the album: this was the first piece we performed together, and I don’t think either of us will ever forget the sight of a muscular Russian ballerina pirouetting towards us on the Royal Opera House stage while we played, before sinking to the ground – as the Dying Swan – mere feet away. An exhilarating memory, which paved the way for many more unforgettable adventures in music and life… Here’s to the next 19 years and beyond!

© Tom Poster and Guy Johnston 2018

Guy Johnston is one of the most exciting British cellists of his generation, with early successes including winning the BBC Young Musician of the Year as well as a Classical Brit. He performs with many leading international orchestras including the London Philharmonic, Philharmonia, English Chamber Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Deutsches Symphonie Orchester Berlin, Orquestra Sinfonica do Estado de Sao Paulo, NHK Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo, Moscow Philharmonic and St Petersburg Symphony; he also appears regularly in major international festivals, such as the BBC Proms.

In recent seasons, he has given the premieres of the Howells Cello Concerto and Charlotte Bray’s Falling in the Fire, as well as concertos with the Royal Northern Sinfonia, Sibelius with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and Holst and Tchaikovsky with the BBC Philharmonic.

As a chamber musician, Guy gives concerts in Europe and throughout the UK, in venues including Wigmore Hall, working with distinguished chamber music partners such as Kathryn Stott, Melvyn Tan and the Navarra and Endellion Quartets.

Guy is Artistic Director of the Hatfield House Chamber Music Festival, a guest Professor of Cello at the Royal Academy of Music and a member of the faculty at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. He is a founder member of the Aronowitz Ensemble and the Aronowitz Piano Trio.

His mentors have included Steven Doane, Ralph Kirshbaum, Bernard Greenhouse, Steven Isserlis, David Waterman and Anner Bylsma.

Guy plays a 1714 David Tecchler cello, generously on loan from the Godlee-Tecchler Trust which is administered by The Royal Society of Musicians.

Tom Poster is a musician whose skills and passions extend well beyond the conventional role of the concert pianist. He has been described as “a marvel, [who] can play anything in any style” (The Herald), “mercurially brilliant” (The Strad), and as having “a beautiful tone that you can sink into like a pile of cushions” (BBC Music).

Tom has performed more than forty concertos ranging from Bach to Ligeti with the Aurora Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, BBC Scottish Symphony, China National Symphony, Hallé, Philharmonia, Royal Philharmonic, Scottish Chamber Orchestra and St Petersburg State Capella Philharmonic, collaborating with conductors such as Vladimir Ashkenazy, Nicholas Collon, Thierry Fischer, Robin Ticciati and Yan Pascal Tortelier.

Tom features regularly on BBC radio and television and has made multiple appearances at the BBC Proms, and his exceptional versatility has put him in great demand at festivals internationally. He is a regular performer at Wigmore Hall, and is pianist of the Aronowitz Ensemble (former BBC New Generation Artists) and the Aronowitz Piano Trio. He enjoys established duo partnerships with Alison Balsom, Guy Johnston and Elena Urioste, and also collaborates with Ian Bostridge, Steven Isserlis, Matthew Rose and the Danish, Navarra and Škampa Quartets.

Tom has recorded solo discs for Champs Hill Records and Edition Classics, chamber music for Chandos, Decca Classics and Warner Classics, and regularly features as soloist on film soundtracks, including the Oscar-nominated score for The Theory of Everything. He studied with Joan Havill at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and at King’s College, Cambridge.

Increasingly in demand as a curator and innovative concert programmer, Tom is artistic director of Kaleidoscope Chamber Collective, an ensemble with a flexible line-up and an ardent commitment to diversity. He is also a successful composer and arranger, and a lifelong fan of animals with unusual noses.

James Gilchrist’s musical interest was fired at a young age, singing first as a chorister in the choir of New College, Oxford, and later as a choral scholar at

King’s College, Cambridge.

James’ extensive concert repertoire has seen him perform in major concert halls throughout the world. A master of English music, he has performed Britten’s Church Parables in St Petersburg, London and at the Aldeburgh Festival, Nocturne with the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Tokyo and War Requiem with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. James is famed for his interpretations of Bach, and has performed Christmas Oratorio with the Academy of Ancient Music, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, further afield with Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra in Toronto and across Europe. The St John and St Matthew Passions feature prominently in his schedule, and he is celebrated as perhaps the finest Evangelist of his generation.

Highlights include the role of Reverend Horace Adams in Britten’s Peter Grimes with Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and Edward Gardner with performances at the Edinburgh International Festival, Haydn’s Creation for a staged production with Garsington Opera and Ballet Rambert, as well as performances with Aarhus Symphony Orchestra, Denmark, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and Bach Collegium Japan under the baton of Masaaki Suzuki. In 2017, James celebrated 20 years of collaboration with pianist Anna Tilbrook. Recent performances together include a new project for Wigmore Hall – Schumann and the English Romantics – pairing Schumann song cycles with new commissions from leading composers Sally Beamish, Julian Philips and Jonathan Dove.

James has made over 30 recordings including Albert Herring (title role) and Vaughan Williams’ A Poisoned Kiss for Chandos, St John Passion with the AAM, and the critically-acclaimed recordings of Schubert’s song cycles for Orchid Classics.

www.jamesgilchrist.co.uk