Artist Led, Creatively Driven

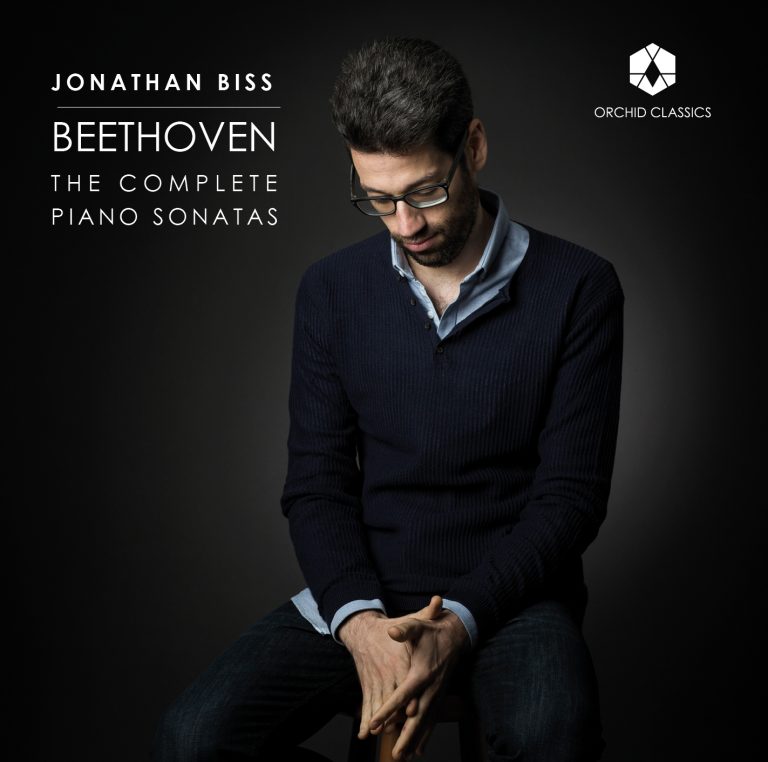

Jonathan Biss

Beethoven

Piano Sonatas vol.1

Release Date: 2020

ORC100118

PIANO SONATAS, Vol 1

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Sonata No.5 in C minor, Op.10 No.1

1 Allegro molto e con brio 5.18

2 Adagio molto 7.23

3 Prestissimo 4.11

Piano Sonata No.11 in B flat major, Op.22

4 Allegro con brio 7.24

5 Adagio con molt’espressione 6.37

6 Menuetto 3.12

7 Rondo: Allegretto 6.26

Piano Sonata No.12 in A flat major (‘Funeral March’), Op.26

8 Andante con variazioni 6.56

9 Scherzo. Allegro molto 2.37

10 Maestoso andante, marcia funebre sulla morte d’un eroe 5.20

11 Allegro 2.53

Piano Sonata No.26 in E flat major (‘Les Adieux’), Op.81a

12 Das Lebewohl. Adagio – Allegro 6.53

13 Abwesenheit. Andante espressivo

(In gehender Bewegung, doch mit viel Ausdruck) 3.08

14 Das Wiedersehen. Vivacissimamente

(Im lebhaftesten Zeitmaße) 5.35

Total time 74.10

Sonatas 5, 11, 12 & 26 (‘Les Adieux’)

The 32 Beethoven piano sonatas are often referred to as one of the greatest – if not the greatest – bodies of music ever composed. True enough. But to refer to them as such is to obscure the brilliance and individuality of each work, for what is perhaps most remarkable about the sonatas is that they really aren’t a ‘body of music’ at all: they are 32 masterpieces, 32 distinct structures, 32 fully realized, often awe-inspiring, always unique emotional universes. As individual works, each is endlessly compelling on its own merits; as a cycle, it moves from transcendence to transcendence, the basic concerns always the same, but the language impossibly varied.

In the end, I think, it is the nature of these concerns – which could crudely be described as being of the ‘man versus universe’ variety – which unites this music, in spite of the incredible amount of ground it covers both formally and stylistically. A favourite cliché about Beethoven is that he moved from thumbing his nose at the traditionalists in his first period, to magnificence in the middle one, to spirituality in the late. (Even the idea of three periods is a cliché, in fact – a figure as complex as Beethoven will probably always be vulnerable to over- simplification, and his compositional style was in a perpetual state of evolution.) But in fact, the last sonatas betray no lessening in his gruffness, or desire to shock, and the earliest ones have slow movements which already seem to stop time. (And this is to say nothing of the moments of extraordinary tenderness in the middle works.) And so it is with Op.10 No.1. The middle movement forms an oasis of profound beauty, always searching, yet with a deep stillness grounding it. ‘Oasis’, because the music which surrounds it is among the most restless Beethoven wrote. This is one of the first of Beethoven’s many works in C minor, and the qualities one associates with this composer in this key – anxiety, rage, the shaking of the fist – are fully in evidence here. Beethoven was, throughout his life, attracted to opposition, to dichotomy, of character and feeling – in no other composer’s music do the tender and the furious coexist so closely – and in this sonata that idea is extended to tempo: where the outer movements are meant to quicken the pulse not only of the player, but the listener, life itself slows down for the second movement. Or: if the fast movements grapple with a world which infuriated Beethoven, the slow one imagines a different, more perfect one.

Where Op.10 No.1, like so many of its neighbours, shows Beethoven inventing, Op.22 feels very much like a summation. Despite the early opus number, Beethoven had by this point written more than a third of his piano sonatas, and in this work – a particular favourite of his – he demonstrates an enormous ease and confidence with the form; the sonata’s ideas sound as if they had simply flown from the composer’s pen. Beethoven surely had as restless an imagination as any great artist, but in this sonata we find him looking more backwards than forwards; the last two movements in particular adhere closely to a model he had established, and throughout the piece, one is reminded of one or another of the previous sonatas. But while the sonata is revolutionary neither in form nor in content, it is no less marvellous for it: the impish wit of the work’s opening, for example, or the never-ending, heaven-directed song of the second movement are indicative of a master revelling in his own mastery.

It may be that this mastery came slightly too easily for Beethoven’s liking, for the next four sonatas find him experimenting with form as boldly and as variously as any group of works he wrote. It is astonishing that the first of these, the Opus 26, was written within a year of Op.22, its immediate predecessor; the only thing the two works have in common is that they are unjustly neglected – one hardly ever hears either, other than in the context of a complete cycle of the sonatas. While the 20th and 21st centuries may not have taken notice of this lovely and slightly peculiar masterpiece, the 19th certainly did: it was the funeral march from this sonata, not the ‘Eroica’ Symphony, which was played at Beethoven’s own funeral, and Chopin – almost alone among great musicians in his general indifference to Beethoven – admired it greatly, and was surely influenced by it. The aforementioned funeral march is the most obvious manifestation of that influence, but one imagines that Chopin was equally struck by the almost total absence of grand gesture, of rhetoric, throughout the work. The sonata opens with a theme of disarming simplicity and beauty, which – unprecedented in Beethoven’s output – becomes the basis not of a sonata movement, but a set of variations. So instead of developing – not to say manipulating – the theme, he embroiders it, allowing it to expand and contract, to unfold of its own accord. So often in Beethoven, one feels the composer attempting (and virtually always succeeding) to bend the material to his will; in this work, even in the funeral march, dedicated to ‘A Hero’, nothing ever feels imposed on the motives. The form of the Op.26 may be unprecedented, but after the brilliance and bluster of the early sonatas, its quiet confidence and utter absence of any attempt to ingratiate may be its most striking features.

Being ingratiating, of course, dropped ever lower on Beethoven’s list of priorities as he aged, and while there is no shortage of beauty in the works of his last two decades, it is increasingly a rugged, even gnarled beauty, and one always at the service of the idea at hand. And the ideas themselves grow ever bolder – less and less reliant on any convention of musical language. This sort of innovation did not come easily: Beethoven’s first 20 sonatas were composed in the space of seven years, from 1795 to early 1802; the subsequent seven years saw the composition of only five, and it was not until 1810 that the ‘Les Adieux’ Sonata (Lebewohl, in German, No.26) was completed. Conventional wisdom says that Beethoven’s late style was still several years away, but this work, despite the almost reckless exuberance of its finale, has an interiority which is a hallmark of every subsequent sonata he composed. (The ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata’s magnificently impenetrable slow movement is enough to make it qualify, despite the grandness of the rest of the piece.)

And accordingly, nothing about the sonata is business as usual. Its most obviously unique feature is its programmatic nature: whereas the Pastoral Symphony is programmatic only in the sense that it attempts to evoke the feelings attached to certain events, the ‘Les Adieux’ first movement is permeated with a three-note motif – actually marked Le–be–wohl at the sonata’s opening – obviously intended to mimic a horn call, a formal gesture of 45 parting. While nothing in the second or third movements conveys in such a literal way the absence and return, respectively, of Archduke Rudolph, the sonata’s dedicatee and inspiration, the idea of a formal narrative has been planted so firmly in our heads by this point that we can supply the imagery ourselves.

More significant are the sonata’s formal innovations. What is so striking about the first movement is that while its body – its exposition, development and recapitulation – is perhaps the most compact of any of Beethoven’s movements in sonata form, it is flanked by an introduction and coda of extreme spaciousness. While this might in theory make the movement ungainly – think gigantic limbs attached to a modest torso – in reality, these appendages, in being far longer than one would expect, prove enormously effective in illustrating the pain of parting. This is the genius of Beethoven: his formal innovations are never theoretical, or merely ‘ideas’; his forms become maps of the works’ emotional content, of their truest nature.

There is one final way in which the ‘Les Adieux’ sonata points the way towards Beethoven’s last works. Early in his compositional career, Beethoven was content for his last movements to round the works off; this rounding off might be graceful (Op.22), or brash (Op.10 No.1), but there is nothing in these movements to alter the general course of the works. As Beethoven grew older, his conception of the multi-movement work changed so that ultimately he viewed them as emotional trajectories which were not resolved until the final notes were played. This is very much in evidence in ‘Les Adieux’. The last movement provides the work with a resolution not only because a movement called ‘The Absence’ must inevitably be followed by a return, but because the emotional ambiguity which permeates the first two movements absolutely demands the uncomplicated joy of the last.

Perhaps it is these two qualities – the complexity and ambiguity on the one hand, the optimism and occasionally even euphoria on the other – which best define what the Beethoven sonatas represent. To embark on this journey is thus both awe-inducing, and pure delight.

Jonathan Biss

Pianist Jonathan Biss’s approach to music is a holistic one. In his own words: I’m trying to pursue as broad a definition as possible of what it means to be a musician. As well as being one of the world’s most sought-after pianists, a regular performer with major orchestras, concert halls and festivals around the globe and co-Artistic Director of Marlboro Music, Jonathan Biss is also a renowned teacher, writer and musical thinker.

His deep musical curiosity has led him to explore music in a multi-faceted way. Through concerts, teaching, writing and commissioning, he fully immerses himself in projects close to his heart, including Late Style, an exploration of the stylistic changes typical of composers – Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Britten, Elgar, Gesualdo, Kurtág, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann – as they approached the end of life, looked at through solo and chamber music performances, masterclasses and a Kindle Single publication Coda; and Schumann: Under the Influence a 30-concert initiative examining the work of Robert Schumann and the musical influences on him, with a related Kindle publication A Pianist Under the Influence.

This 360° approach reaches its zenith with Biss and Beethoven. In 2011, he embarked on a nine-year, nine-album project to record the complete cycle of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. Starting in September 2019, in the lead-up to the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth in December 2020, he will perform a whole season focused around Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, with more than 50 recitals worldwide. This includes performing the complete sonatas at Wigmore Hall and Berkeley, multi-concert-series in Washington, Philadelphia, and Seattle, as well as recitals in Rome, Budapest, New York and Sydney.

One of the great Beethoven interpreters of our time, Biss’s fascination with Beethoven dates back to childhood and Beethoven’s music has been a constant throughout his life. In 2011 Biss released Beethoven’s Shadow, the first Kindle eBook to be written by a classical musician. He has subsequently launched Exploring Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, Coursera’s online learning course that has reached more than 150,000 subscribers worldwide; and initiated Beethoven/5,a project to commission five piano concertos as companion works for each of Beethoven’s piano concertos from composers TimoAndres, Sally Beamish, Salvatore Sciarrino, Caroline Shaw and Brett Dean. The latter will be premiered in February 2020 with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and subsequently performed by orchestras in USA, Germany, France, Poland and Australia.

As one of the first recipients of the Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award in 2003, Biss has a long-standing relationship with Mitsuko Uchida with whom he now enjoys the prestigious position of Co-Artistic Director of Marlboro Music. Marlboro holds a special place for Biss, who spent twelve summers there, and for whom nurturing the next generation of musicians is vitally important. Biss continues his teaching as Neubauer Family Chair in Piano Studies at Curtis Institute of Music.

Biss is no stranger to the world’s great stages. He has performed with major orchestras across the US and Europe, including New York Philharmonic, LA Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, CBSO, London Philharmonic Orchestra and Concertgebouw. He has appeared at the Salzburg and Lucerne Festivals, has made several appearances at Wigmore Hall and Carnegie Hall, and is in demand as a chamber musician.

He was the first American to be named a BBC New Generation Artist, and has been recognised with many other awards including the Leonard Bernstein Award presented at the 2005 Schleswig-Holstein Festival, Wolf Trap’s Shouse Debut Artist Award, the Andrew Wolf Memorial Chamber Music Award, Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award, an Avery Fisher Career Grant, the 2003 Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award, and the 2002 Gilmore Young Artist Award.

Surrounded by music from an early age, Jonathan Biss is the son of violist and violinist Paul Biss and violinist Miriam Fried, and grandson of cellist Raya Garbousova (for whom Samuel Barber composed his cello concerto). He studied with Leon Fleisher at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, and gave his New York recital debut aged 20.