Artist Led, Creatively Driven

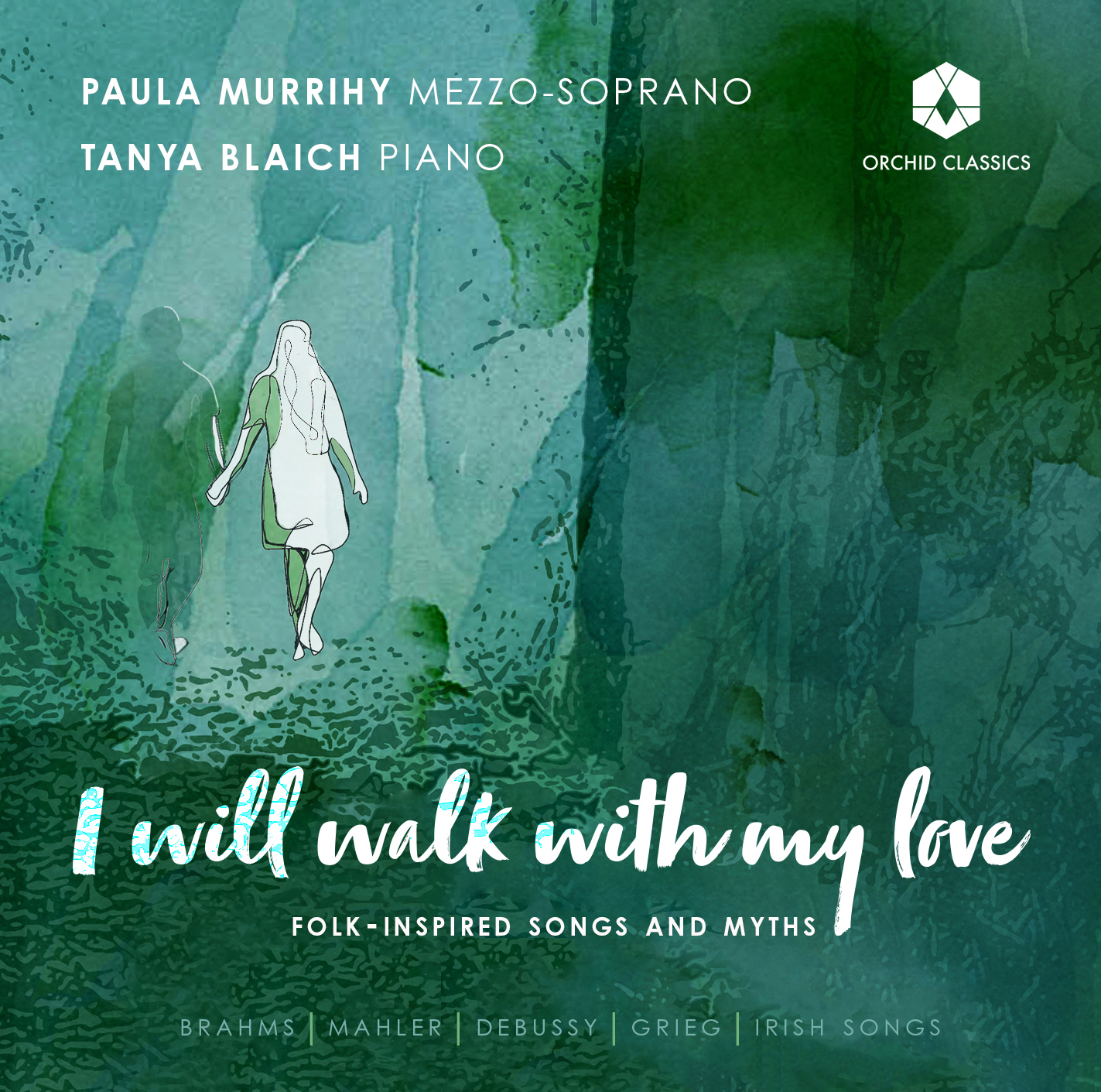

I will walk with my love

Folk inspired songs and myths

Paula Murrihy, mezzo-soprano

Tanya Blaich, piano

Release Date: October 2nd 2020

ORC100144

I WILL WALK WITH MY LOVE: Folk-inspired Songs and Myths

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

1 Da unten im Tale (49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033) 2.44

2 Ständchen, Op.14, No.7 1.53

3 Wie komm’ ich denn zur Tür herein

(49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033) 2.24

4 Es steht ein Lind (49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033) 2.48

5 Bei dir sind meine Gedanken, Op.95, No.2 2.07

6 Vergebliches Ständchen, Op.84, No.4 2.03

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

From Des Knaben Wunderhorn

7 Rheinlegendchen 3.24

8 Ich ging mit Lust 5.13

9 Verlor’ne Müh 2.53

10 Das irdische Leben 3.10

11 Urlicht 5.33

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Chansons de Bilitis, L97

12 La flûte de Pan 3.00

13 La chevelure 3.45

14 Le tombeau des Naïades 2.53

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

Sechs Lieder, Op.48

15 Gruss 1.14

16 Dereinst, Gedanke mein 3.20

17 Lauf der Welt 1.48

18 Die verschwiegene Nachtigall 3.41

19 Zur Rosenzeit 3.22

20 Ein Traum 2.20

Irish Folk Songs

21 I Will Walk With My Love (Hughes/traditional) 1.49

22 An Old Woman of the Roads (Victory/Colum) 3.07

23 The Salley Gardens (Britten/Yeats) 3.02

24 Wee Hughie (Larchet/Shane) 3.02

25 The Wee Boy in Bed (Larchet/Shane) 3.40

Total time 74.15

Paula Murrihy, mezzo-soprano

Tanya Blaich, piano

I Will Walk With My Love: Folk-inspired Songs and Myths. There’s a reason songs about love are so ubiquitous – love is an endlessly rewarding source of inspiration and exploration! The bookends of the album are Brahms’ Da unten im Tale and Herbert Hughes’ I Will Walk With My Love, and they encapsulate the parameters of this journey. Brahms’ classic German folk song walks us through the phases of lament, frustration, reconciliation and transcendence in a love relationship, almost like a Bach Cantata, but in under 3 minutes. I Will Walk With My Love widens the span to the beginnings of love: we hear of building a bower for the beloved in one’s breast, and in the next verse the text leaps forward to the transcendent phase post-breakup, but the brilliant and simple folk truth concludes that love in some form is still there – ”I will walk with my love now and then.” The rest of the album then explores everything in between: falling in love, courting, missing a beloved far away, love affairs, and love’s rejection. We make brief excursions to other expressions of love – love of God, love of family and one’s children.

These are not all folk songs or texts, strictly speaking – but there is something folk-like in many of them. All of these songs, even the truest of folk texts or songs, are lacking squeaky clean authenticity. Arnim and Brentano edited or invented parts of the poems they collected in Des Knaben Wunderhorn, and Mahler added his own edits to these folk texts. Zuccalmaglio invented or edited the poems in his folk collections, and Louÿs claimed his texts for Debussy’s Bilitis songs were translations of an ancient Greek poetess which later turned out to be a hoax. Grieg is known for his folk song style and many of the songs in Op.48 feel folk-like in their directness and simplicity, yet they cannot be claimed as folk songs. Britten put his own unmistakable personal stamp on his arrangements of folk songs and was not primarily concerned with authenticity. Yet in all these songs, we receive the enchanting and simple, unassuming insights into the human condition. They address universal experiences that have the power to speak across social, class and cultural boundaries.

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Da unten im Tale

Aus 49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033

Da unten im Tale

Läuft’s Wasser so trüb,

Und i kann dir’s net sagen,

i hab’ di so lieb.

Sprichst allweil von Liebe,

Sprichst allweil von Treu’,

Und a bissele Falschheit

Is auch wohl dabei.

Und wenn i dir’s zehnmal sag,

Daß i di lieb,

Und du willst nit verstehn,

Muß i halt weitergehn.

Für die Zeit, wo du gliebt mi hast,

Dank i dir schön,

Und i wünsch, daß dir’s anderswo

Besser mag gehn.

Ständchen

Franz Theodor Kugler (1808-1858)

Der Mond steht über dem Berge,

So recht für verliebte Leut’;

Im Garten rieselt ein Brunnen,

Sonst Stille weit und breit.

Neben der Mauer im Schatten,

Da stehn der Studenten drei,

Mit Flöt’ und Geig’ und Zither,

Und singen und spielen dabei.

Die Klänge schleichen der Schönsten

Sacht in den Traum hinein,

sie schaut den blonden Geliebten

und lispelt: “Vergiß nicht mein!”

Wie komm’ ich denn zur Tür herein

Aus 49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033

Er: Wie komm’ ich denn zur Tür herein,

sag’ du, mein Liebchen, sag’?

Sie: Nimm den Ring und zieh’ die Klink,

dann meint die Mutt’r es wär’ der Wind,

komm’ du, mein Liebchen komm’!

Er: Wie komm’ ich denn vorbei dem Hund?

sag’ du, mein Liebchen, sag’?

Sie: Gib dem Hund ein gutes Wort,

dann geht er wied’r an seinen Ort,

komm’ du, mein Liebchen komm’!

Er: Wie komm’ ich denn vorbei dem Feu’r,

sag’ du, mein Liebchen, sag’?

Sie: Schütt ein bißchen Wasser drein,

dann meint die Mutt’r es regnet ‘rein,

komm’ du, mein Liebchen komm’!

Er: Wie komm’ ich denn die Trepp’ hinauf,

sag’ du, mein Liebchen, sag’?

Sie: Nimm die Schuh’ nur in die Hand

und schleich’ dich leis’ entlang der Wand,

komm’ du, mein Liebchen komm’!

Es steht ein’ Lind’

Aus 49 Deutsche Volkslieder Wo033

Es steht ein’ Lind’ in jenem Tal,

ach Gott, was tut sie da?

Sie will mir helfen trauren, trauren,

daß ich mein’ Lieb’ verloren hab’.

Es sitzt ein Vöglein auf dem Zaun,

ach Gott, was tut es da?

Es will mir helfen klagen, klagen,

daß ich mein’ Lieb’ verloren hab’.

Es quillt ein Brünnlein auf dem Plan,

ach Gott, was tut es da?

Es will mir helfen weinen, weinen,

daß ich mein’ Lieb’ verloren hab’.

Bei dir sind meine Gedanken

Friedrich Halm (1806-1871)

Bei dir sind meine Gedanken

Und flattern, flattern um dich her;

Sie sagen, sie hätten Heimweh,

Hier litt’ es sie nicht mehr.

Bei dir sind meine Gedanken

Und wollen von dir, von dir nicht fort;

Sie sagen, das wär’ auf Erden

Der allerschönste Ort.

Sie sagen, unlösbar hielte

Dein Zauber sie festgebannt;

Sie hätten an deinen Blicken

Die Flügel sich verbrannt.

Vergebliches Ständchen

Anton von Zuccalmaglio (1803-1869)

Er: Guten Abend, mein Schatz,

guten Abend, mein Kind!

Ich komm’ aus Lieb’ zu dir,

Ach, mach’ mir auf die Tür,

mach’ mir auf die Tür!

Sie: Meine Tür ist verschlossen,

Ich laß dich nicht ein;

Mutter, die rät’ mir klug,

Wär’st du herein mit Fug,

Wär’s mit mir vorbei!

Er: So kalt ist die Nacht,

so eisig der Wind,

Daß mir das Herz erfriert,

Mein’ Lieb’ erlöschen wird;

Öffne mir, mein Kind!

Sie: Löschet dein’ Lieb’;

lass’ sie löschen nur!

Löschet sie immerzu,

Geh’ heim zu Bett, zur Ruh’!

Gute Nacht, mein Knab’!

Brahms was a great advocate of folk text and song and was the first great German composer to dedicate so much of his composition to this genre. Of his some 200 song compositions, around 70 were folk song settings. As mentioned above, we begin the album with the classic German folk song, Da unten im Tale taken from his 49 Deutsche Volkslieder. We continue with the playful scene of serenading students in Ständchen in the courting phase of love. The piano part seems to suggest the zither or a guitar that one of the students is playing (we later hear of a trio of instruments, zither, flute and violin). Brahms shows his ingenuity in variation of two melodic contours throughout the song. The piano introduces the first melodic gesture that reappears throughout the song in both the voice and piano parts, and is showcased in the long piano interlude depicting the musicians playing wholeheartedly; the opening vocal melody introduces a second melodic contour that is similarly woven into the fabric of both parts throughout this delightful bagatelle in ABA form.

The melody and text of Wie komm’ ich denn zur Tür herein is from Kretzschmar-Zuccalmaglio’s Deutsche Volkslieder mit ihren Originalweisen (German folk songs with their original tunes), but many contend that it most likely was an early 19th century song that Zuccalmaglio used to his advantage. Here the courting process continues, and the lovers are scheming how to meet in one of their bedrooms at home in secret without the parents detecting it!

Es steht ein Lind was included in Brahms’ 49 Deutsche Volkslieder even though it was a contemporary text written by Wilhelm Tappert with a tune purporting to be from Nuremberg from 1550. This song outlines the cathartic process of coming to terms with the loss of a love. The narrator sees a linden tree, that iconic tree which appears in so many German Lieder, often placed at the heart of a village community, and frequently the tree under which lovers meet in folklore. Here the abandoned one feels solidarity in grief from the linden tree. The second verse depicts a bird on a fence that helps the narrator lament the loss in its birdsong. And in the final verse, Brahms slightly, yet significantly alters the harmonic and melodic language to find progression in the grieving process – a flowing spring finally helps the narrator to weep out her pain and find physical release.

A pair of lovers are distant from one another, and the narrator sends her thoughts out to the beloved in Bei dir sind meine Gedanken. The winged thoughts flutter about the beloved in incessantly oscillating 16th notes in the piano part. In the last verse these thoughts have flown too close to the irresistible light of the beloved, and like moths, they have burned their wings. However the music resumes its fluttering in the postlude – it wasn’t fatal!

We return to another serenade in Vergebliches Ständchen, yet this one is in vain! Another poem from Zuccalmaglio’s folk poetry collection, this one originates from the Lower Rhine, where men are direct and women are equally direct. And as in so many Brahms songs, this woman has learned a thing or two from her mother about relationships. Here the suitor is confident in his sexual advances, but she coolly rejects them with coquetry. The lad then threatens (in minor mode) that his love for her will be extinguished out in the cold if she resists his advances. Without hesitation she responds (in major), encouraging him to do just that, yet all in good humour (as Brahms has marked).

GUSTAV MAHLER (1860-1911)

Aus Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Rheinlegendchen

Bald gras’ ich am Neckar,

bald gras’ ich am Rhein;

Bald hab’ ich ein Schätzel,

bald bin ich allein!

Was hilft mir das Grasen,

wenn d’ Sichel nicht schneid’t;

was hilft mir ein Schätzel,

wenn’s bei mir nicht bleibt!

So soll ich denn grasen

am Neckar, am Rhein,

So werf ich mein goldenes

Ringlein hinein.

Es fließet im Neckar

und fließet im Rhein,

Soll schwimmen hinunter

in’s Meer tief hinein.

Und schwimmt es, das Ringlein,

so frißt es ein Fisch!

Das Fischlein tät kommen

auf’s König sein Tisch!

Der König tät fragen,

wem’s Ringlein sollt sein?

Da tät mein Schatz sagen:

das Ringlein g’hört mein!

Mein Schätzlein tät springen

Berg auf und Berg ein,

Tät mir wiedrum bringen

das Goldringlein mein!

Kannst grasen am Neckar,

kannst grasen am Rhein!

Wirf du mir nur immer

dein Ringlein hinein!

Ich ging mit Lust

Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald,

Ich hört’ die Vöglein singen;

Sie sangen so jung, sie sangen so alt,

Die kleinen Waldvöglein im grünen Wald!

Wie gern hört ich sie singen!

Nun sing, nun sing, Frau Nachtigall!

Sing du’s bei meinem Feinsliebchen:

Komm schier, wenn’s finster ist,

Wenn niemand auf der Gasse ist,

Dann komm zu mir! Herein will ich dich lassen!

Der Tag verging, die Nacht brach an,

Er kam zu Feinsliebchen gegangen.

Er klopft so leis’ wohl an den Ring:

“Ei schläfst du oder wachst mein Kind?

Ich hab so lang gestanden!”

Es schaut der Mond durchs Fensterlein

Zum holden, süßen Lieben,

Die Nachtigall sang die ganze Nacht.

Du schlafselig Mägdelein, nimm dich in Acht!

Wo ist dein Herzliebster geblieben?

Verlor’ne Müh

Sie: Büble, wir!

Büble, wir wollen auße gehe!

Wollen wir?

Unsere Lämmer besehe?

Gelt! Komm! Komm! Lieb’s Büberle,

komm’, ich bitt’!

Er: Närrisches Dinterle,

ich geh dir holt nit!

Sie: Willst vielleicht –

Willst vielleicht ä bissel nasche?

Hol’ dir was aus meiner Tasch’!

Hol’, lieb’s Büberle,

hol’, ich bitt’!

Er: Närrisches Dinterle,

ich nasch’dir holt nit!

Sie: Gelt, ich soll –

Gelt? Ich soll mein Herz dir schenke!?

Immer willst an mich gedenke1?

Nimm’s! Lieb’s Büberle!

Nimm’s, ich bitt’!

Er: Närrisches Dinterle,

Ich mag es holt nit!

Das irdische Leben

“Mutter, ach Mutter, es hungert mich!

Gib mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!”

“Warte nur, mein liebes Kind!

Morgen wollen wir ernten geschwind!”

Und als das Korn geerntet war,

Rief das Kind noch immerdar:

“Mutter, ach Mutter! es hungert mich!

Gib mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!”

“Warte nur, mein liebes Kind!

Morgen wollen wir dreschen geschwind!”

Und als das Korn gedroschen war,

Rief das Kind noch immerdar:

“Mutter, ach Mutter! es hungert mich!

Gib mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!”

“Warte nur! Warte nur, mein liebes Kind!

Morgen wollen wir backen geschwind!”

Und als das Brot gebacken war,

Lag das Kind auf der Totenbahr’!

Urlicht

O Röschen rot!

Der Mensch liegt in größter Not!

Der Mensch liegt in größter Pein!

Je lieber möcht’ ich im Himmel sein!

Da kam ich auf einen breiten Weg;

Da kam ein Engelein und wollt’ mich abweisen.

Ach nein, ich ließ mich nicht abweisen!

Ich bin von Gott und will wieder zu Gott!

Der liebe Gott wird mir ein Lichtchen geben,

Wird leuchten mir bis in das ewig selig’ Leben!

Mahler was a champion of the folk idiom, as is evident in his frequent use of folk poetry and the incorporation of folk music and dance in his compositions. More than half of his song compositions are set to texts from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn), a 3-volume set of folk poetry collected by Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim and first published in 1805. Just like Brahms, Arnim and Brentano were not overly concerned with issues of authenticity, as they freely added to or subtracted from these poems and even invented new ones entirely. They dedicated the work to Goethe, who recommended that every household have a copy, kept next to other essentials like the German cookbook and book of songs.

Mahler marks Rheinlegendchen with “kindlich-schalkhaft und innig” (childish-mischievous and heartfelt) and sets the song to a typical Austrian folk dance, the Ländler. The poem seems to welcome grazing for love along various shores, and mischievously traces the adventures of the narrator’s ring, which he tosses into the Rhine. He concludes that he is fine with the “travels” as long as that ring and his lover keep coming back to him. The word “grasen” in the poem is frequently translated as “mow,” taking its cues from the second verse about mowing and the sickle not cutting properly, but this overlooks the double entendre and sexual implications of “grazing” in the context of love relationships in the poem, and especially in the context of the first and last verses. The Grimm Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (The Grimm Dictionary of the German Language) published in 1854 first defines “grasen” as “to mow”, then later lists: The grazing of young maidens and women is a favorite literary motif in the context of love affairs

The nightingale, frequently a symbol for love and often of absent love, dominates in Ich ging mit Lust and suggests that something is awry in this love story. A maiden is awaiting a nighttime visit from her lover, and bids the nightingale to sing to him, reminding him of their evening’s tryst. The lover finally makes an appearance, but he is much later than expected, and he professes to have waited a long time in front of her door without her noticing or letting him in. The piano interlude right after makes a subtle melodic shift, and then Mahler replaces the final two verses with his own original verse wherein the narrator warns the maiden to watch out and asks, where did your sweetheart go? There is no verbal answer, and Mahler’s nightingale continues to sing as we ponder.

A maiden woos a lad in vain in Verlor’ne Müh, which alternates between his voice and hers in a Bavarian-Swabian dialect. Mahler adds significant text repetitions of the woman’s advances, making her questions humorously annoying and naïve in rising, rangy melodic gestures in another leisurely Ländler. The offers become ever more daring and desperate, offering him a “snack”, and finally even offering her heart with a bit of trepidation – all to no avail and to the increasing annoyance of the lad.

The dramatic ballad Das irdische Leben reminds us of Schubert’s Der Erlkönig, and eerily foreshadows Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder. Here a child faces starvation and cries out for bread while the mother repeatedly tells the child to just wait a little longer – now the harvest, now the threshing, then finally the baking of the bread. The stormy 16th notes in the piano drive relentlessly, only becoming more lyrical and even dance-like with the mother’s somewhat blithe answers. The storm finally subsides at the end after we learn the harrowing news that just as the bread finished baking, the child perished. Mahler wrote that he saw a much more important analogy for human life in this parable: we keep postponing essential sustenance for body and soul until it is too late.

Mahler incorporated Urlicht into the fourth movement of his Second Symphony, the “Resurrection Symphony.” Primal Light expresses the intense longing to return to God, given the immense turmoil and suffering present in humanity. Beginning with an initial address to “O little red rose!” (perhaps Christ, the rose of Jesse?), the piano solemnly sings a Bach-like chorale full of intense yearning and conviction. When an angel tries to block her way to heaven, she states fervently and lovingly (Mahler marks “passionately, but tenderly”) that she will not be deterred. The Gospels of Luke and Matthew instruct believers in the forceful character necessary to gain the kingdom of heaven. Here the narrator peacefully resists the deterring angel and perseveres in her journey to reunite with the primal light.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

3 Chansons de Bilitis

Pierre Louÿs (1970-1925)

La flûte de Pan

Pour le jour des Hyacinthies,

il m’a donné une syrinx faite

de roseaux bien taillés,

unis avec la blanche cire

qui est douce à mes lèvres comme le miel.

Il m’apprend à jouer, assise sur ses genoux;

mais je suis un peu tremblante.

Il en joue après moi,

si doucement que je l’entends à peine.

Nous n’avons rien à nous dire,

tant nous sommes près l’un de l’autre;

mais nos chansons veulent se répondre, et tour à tour

nos bouches s’unissent sur la flûte.

Il est tard;

voici le chant des grenouilles vertes

qui commence avec la nuit.

Ma mère ne croira jamais

que je suis restée si longtemps à chercher ma ceinture perdue.

La chevelure

Il m’a dit: «Cette nuit, j’ai rêvé.

J’avais ta chevelure autour de mon cou.

J’avais tes cheveux comme un collier noir

autour de ma nuque et sur ma poitrine.

«Je les caressais, et c’étaient les miens;

et nous étions liés pour toujours ainsi,

par la même chevelure, la bouche sur la bouche,

ainsi que deux lauriers n’ont souvent qu’une racine.

«Et peu à peu, il m’a semblé,

tant nos membres étaient confondus,

que je devenais toi-même,

ou que tu entrais en moi comme mon songe.»

Quand il eut achevé,

il mit doucement ses mains sur mes épaules,

et il me regarda d’un regard si tendre,

que je baissai les yeux avec un frisson.

Le tombeau des Naïades

Le long du bois couvert de givre, je marchais;

Mes cheveux devant ma bouche

Se fleurissaient de petits glaçons,

Et mes sandales étaient lourdes

De neige fangeuse et tassée.

Il me dit: “Que cherches-tu?”

Je suis la trace du satyre.

Ses petits pas fourchus alternent

Comme des trous dans un manteau blanc.

Il me dit: “Les satyres sont morts.

“Les satyres et les nymphes aussi.

Depuis trente ans, il n’a pas fait un hiver aussi terrible.

La trace que tu vois est celle d’un bouc.

Mais restons ici, où est leur tombeau.”

Et avec le fer de sa houe il cassa la glace

De la source ou jadis riaient les naïades.

Il prenait de grands morceaux froids,

Et les soulevant vers le ciel pâle,

Il regardait au travers.

Pierre Louÿs published “Les chansons de Bilitis” in 1895, claiming they were translations of the ancient Greek poetess Bilitis. These were erotically charged texts and considered socially risqué, but their status as translations from the Greek made them socially acceptable and even regarded as high art. In the preface, Louÿs described Bilitis’ tomb where her writings were found on the walls. Many archaeologists and scholars supported his claims and some even purported to have known Bilitis’ writings for some time. A few years later, Louÿs admitted that he had authored these texts, and the literary hoax became a scandal!

Louÿs traces Bilitis’ life experiences over 143 prose poems. The three texts that Debussy set offer three windows into Bilitis’ experiences of love. Debussy utilizes modality and pentatonic scales to evoke Greek antiquity, reflecting the influence of the Javanese gamelan which he had heard at the Paris Exhibition in 1889. He composed these while working on Pelléas et Mélisande, and the vocal line masterfully portrays the natural inflection of spoken French.

La flûte de Pan shows Bilitis’ sensual awakening as she encounters a shepherd who teaches her to play the panpipes. In Greek myth, Pan pursued the nymph Syrinx, and Diana transformed her into a reed to help her escape. Pan cut these reeds to create a panpipe, and this flute music is heard throughout the piano part. In La chevelure, Bilitis experiences mature sexual love. Everything is intertwined and reciprocal – hair, mouths, limbs – and they have become one another. Le Tombeau des Naïades suggests the waning and deterioration of passion. The text is full of frozen images in winter, and Debussy creates a hypnotic, numb trudging in the piano that takes us to the tomb of the satyrs, nymphs and naiads, and the traces of Bilitis’ past. Her companion tells her that these mythological creatures are long dead, and he breaks ice from the frozen spring where they once lived. The piece ends as he lifts the frozen ice up to the sunlight, peering through it to Bilitis’ past.

EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907)

Gruss

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856)

Leise zieht durch mein Gemüt

Liebliches Geläute,

Klinge, kleines Frühlingslied,

Kling hinaus ins Weite.

Kling hinaus bis an das Haus,

Wo die Veilchen sprießen,

Wenn du eine Rose schaust,

Sag, ich laß sie grüßen.

Dereinst, Gedanke mein

Emanuel Geibel (1815-1884)

Dereinst,

Gedanke mein,

Wirst ruhig sein.

Läßt Liebesglut

Dich still nicht werden:

In kühler Erden,

Da schläfst du gut;

Dort ohne Lieb’

und ohne Pein

Wirst ruhig sein.

Was du im Leben

Nicht hast gefunden,

Wenn es entschwunden

Wird’s dir gegeben.

Dann ohne Wunden

Und ohne Pein

Wirst ruhig sein.

Lauf der Welt

Johann Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862)

An jedem Abend geh’ ich aus

Hinauf den Wiesensteg.

Sie schaut aus ihrem Gartenhaus,

Es stehet hart am Weg.

Wir haben uns noch nie bestellt,

Es ist nur so der Lauf der Welt.

Ich weiß nicht, wie es so geschah,

Seit lange küss’ ich sie,

Ich bitte nicht, sie sagt nicht: ja!

Doch sagt sie: nein! auch nie.

Wenn Lippe gern auf Lippe ruht,

Wir hindern’s nicht, uns dünkt es gut.

Das Lüftchen mit der Rose spielt,

Es fragt nicht: hast mich lieb?

Das Röschen sich am Taue kühlt,

Es sagt nicht lange: gib!

Ich liebe sie, sie liebet mich,

Doch keines sagt: ich liebe dich!

Die verschwiegene Nachtigall

Walther von der Vogelweide (c.1170 – c.1230)

Unter der Linden,

An der Haide,

Wo ich mit meinem Trauten saß,

Da mögt ihr finden,

Wie wir beide

Die Blumen brachen und das Gras.

Vor dem Wald mit süßem Schall,

Tandaradei!

Sang im Thal die Nachtigall.

Ich kam gegangen

Zu der Aue,

Mein Liebster kam vor mir dahin.

Ich ward empfangen,

Als hehre Fraue,

Daß ich noch immer selig bin.

Ob er mir auch Küsse bot?

Tandaradei!

Seht, wie ist mein Mund so roth!

Wie ich da ruhte,

Wüßt’ es Einer,

Behüte Gott, ich schämte mich.

Wie mich der Gute

Herzte, keiner

Erfahre das als er und ich–

Und ein kleines Vögelein,

Tandaradei!

Das wird wohl verschwiegen sein.

Zur Rosenzeit

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Ihr verblühet, süße Rosen,

Meine Liebe trug euch nicht;

Blühet, ach! Dem Hoffnungslosen,

Dem der Gram die Seele bricht!

Jener Tage denk’ ich trauernd,

Als ich, Engel, an dir hing,

Auf das erste Knöspchen lauernd

Früh zu meinem Garten ging;

Alle Blüten, alle Früchte

Noch zu deinen Füßen trug

Und vor deinem Angesichte

Hoffnung in dem Herzen schlug.

Ihr verblühet, süße Rosen,

Meine Liebe trug euch nicht;

Blühet, ach! Dem Hoffnungslosen,

Dem der Gram die Seele bricht.

Ein Traum

Friedrich von Bodenstedt (1819-1892)

Mir träumte einst ein schöner Traum:

Mich liebte eine blonde Maid;

Es war am grünen Waldesraum,

Es war zur warmen Frühlingszeit:

Die Knospe sprang, der Waldbach schwoll,

Fern aus dem Dorfe scholl Geläut –

Wir waren ganzer Wonne voll,

Versunken ganz in Seligkeit.

Und schöner noch als einst im Traum

Begab es sich in Wirklichkeit –

Es war am grünen Waldesraum,

Es war zur warmen Frühlingszeit:

Der Waldbach schwoll, die Knospe sprang,

Geläut erscholl vom Dorfe her –

Ich hielt dich fest, ich hielt dich lang –

Und lasse dich nun nimmermehr!

O, frühlingsgrüner Waldesraum!

Du lebst in mir durch alle Zeit –

Dort ward die Wirklichkeit zum Traum,

Dort ward der Traum zur Wirklichkeit!

Edvard Grieg’s songs are all inextricably linked to his wife, the lyric soprano Nina Hagerup. She was his muse in composition and a strong advocate and interpreter of his songs in performance. Grieg confessed that he owed his creative genius to his love for her. The first two songs of Grieg’s Op.48 were composed in 1884 after a difficult time in their marriage, which also caused a lull in his creative output. After reconciliation, he launched back into song composition with the delightful Gruss to a text by Heine that giddily welcomes back springtime and greets a particular rose that symbolizes a lover. Dereinst Gedanke mein to a text by Geibel, by contrast, longs to be free of love’s torment and recognizes that this will only come with death. Grieg creates a strophic setting with a hymn-like texture that invites a meditative approach.

The remaining four songs were composed in 1889 and continue to explore the themes of love, beginning with courtship in the next two songs which are full of folk-like characteristics. Lauf der Welt is set to a text by Ludwig Uhland, who wrote many of his poems in a folksong style. Grieg sets this text in an ABA form with folk elements such as an oscillating tonic-fifth pedal point in the piano bass line for stretches at a time and jaunty melodic contours to express the inevitability of love between two people like clockwork – it is the way of the world! In a letter to his American biographer Henry Finck in July 1900, Grieg wrote that his songs, arising from his love for Nina, “came to life naturally and through a necessity like that of a natural law.”

Medieval poet and minnesinger Walther von der Vogelweide tells of a love affair with playful, roundabout descriptions in Die verschwiegene Nachtigall: “the grass was crushed…” and “my lips are so red…”. Grieg creates a folk-like aesthetic in the simple, strophic setting. No one knows of this secret love affair except for the ever-present nightingale that sings throughout the piano part and ornaments the vocal line.

Goethe’s Zur Rosenzeit recalls the doubts expressed in Dereinst Gedanke mein and depicts the rose of love (which was just beginning to bud in Gruss) in a wilted state, unable to sustain their relationship. The voice doubles the bass line in angular, drooping, and fragmented phrases, while the right hand of the piano pulses syncopated chords, creating a desolate and hopeless atmosphere. Grieg finds respite in dreamscapes in Ein Traum, text by Friedrich von Bodenstedt, where the nightingale makes two more appearances during dream interludes in fantasies about requited love. Yet the narrator wakes from the dream to find that reality mirrors the dream, making it all the more magical! Piano arpeggiations transform to repeated, pulsing chords that launch the song to blissful heights and triumphant resolve to never let go of this transformative love.

IRISH SONGS

HERBERT HUGHES (1882-1937)

I Will Walk Walk With My Love

Traditional

I once loved a boy and a bold Irish boy

Who would come and would go at my request.

And this bold Irish boy was my pride and joy

And I built him a bower in my breast.

But this girl who has taken my bonny bonny boy

Let her make of him all that she can,

And whether he loves me or loves me not,

I will walk with my love now and then.

GERARD VICTORY (1921-1995)

An Old Woman of the Roads

Padraig Colum (1881-1972)

O, to have a little house!

To own the hearth and stool and all!

The heaped up sods against the fire,

The pile of turf against the wall!

To have a clock with weights and chains

And pendulum swinging up and down!

A dresser filled with shining delph,

Speckled and white and blue and brown!

I could be busy all the day

Clearing and sweeping hearth and floor,

And fixing on their shelf again

My white and blue and speckled store!

I could be quiet there at night

Beside the fire and by myself,

Sure of a bed and loth to leave

The ticking clock and the shining delph!

Och! but I’m weary of mist and dark,

And roads where there’s never a house nor bush,

And tired I am of bog and road,

And the crying wind and the lonesome hush!

And I’m praying to God on high,

And I’m praying Him night and day,

For a little house – a house of my own –

Out of the wind’s and the rain’s way.

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976)

The Salley Gardens

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;

She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;

But I, being young and foolish, with her did not agree.

In a field by the river my love and I did stand,

And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand.

She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs;

But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears.

JOHN F. LARCHET (1884-1967)

Wee Hughie

Elizabeth Shane (1877-1951)

He’s gone to school, Wee Hughie,

An’ him not four.

Sure I saw the fright was in him

When he left the door.

But he took a hand o’ Denny

An’ a hand o’ Dan,

Wi’ Joe’s owld coat upon him –

Och, the poor wee man!

He cut the quarest figure,

More stout nor thin;

An’ trottin’ right an’ steady

Wi his toes turned in.

I watched him to the corner

O’ the big turf stack,

An’ the more his feet went forrit,

Still his head turned back.

He was lookin’,

Would I call him –

Och me heart was woe –

Sure it’s lost I am without him,

But he be to go.

I followed to the turnin’

When they passed it by,

God help him, he was cryin’,

An’, maybe, so was I.

JOHN F. LARCHET

The Wee Boy in Bed

Elizabeth Shane

I mind my granny wi’ her wrinkled hands cardin’ the wool;

I mind my mother at her spinnin’ wheel, on a low stool.

I mind myself…a wee boy in bed, lying so still;

I mind the quare wee lamp that glimmered on the window sill.

I mind my father climbin’ to the loft to work the loom,

I mind the clackin’ noise that it would make down in the room,

An’ well I mind the way I’d be afeart o’ what ‘twould be,

An’ then herself would lave the wheel and come whisperin’ to me.

“Och, whist ye ara-a-thais-ce, turn your face in to the wall,

There’s not a hait o’ harm in the ould loom…at all, at all.”

I mind the way, I mind the way her voice would murmer on close to my ear.

I mind the way I’d hear the crickets singin’ loud and clear.

An’ still I mind the light would flicker dim, the turf burn red.

But I can never mind, can never mind, the big ones when goin’ to bed.

I Will Walk With My Love is a traditional Irish text and tune from County Dublin arranged by Herbert Hughes. As mentioned earlier, it is an Irish version of the subject matter in Brahms’ Da unten im Tale, but here beginning with the blossoming of love, then leaving off in a walk with the now former love, wishing him well with his new partner.

An Old Woman of the Roads was composed by Gerard Victory to a text by Padraig Colum, where a peddler woman is seen leading a nomadic life, selling her wares. She longs for a house of her own, and the simple pleasures of a hearth, sod fire, and a bed of one’s own. She prays to God for a house to keep her safe and warm, if not in this life, then in paradise. Gerard Victory sets the scene in the piano with a pendulum-like clock tick, tracking the passing time and perhaps also representing her constant walking from town to town.

Benjamin Britten longed for his homeland in composing his folk song settings from the British Isles while in America in 1943. He frequently performed these with his lifelong partner, the tenor Peter Pears. The Salley Gardens is an Irish tune to words by W. B. Yeats, which he said he’d adapted from an old folk song. The salley gardens refer to the willow trees where young lovers would meet. As in the previous song, we have a uniting texture throughout the song with flowing, repeated 8th notes (mainly in thirds). This simple and folk-like texture is challenged by the little rising gestures of the piano’s left hand, while the vocal line retains the traditional melody.

The final two songs were composed by John Larchet to texts by Elizabeth Shane, both born in the 1880s. A poet, playwright and violinist, Shane lived most of her life in County Donegal. Larchet studied and later taught at the Royal Irish Academy of Music and his dedication to traditional Irish music led to his appointment as music director of Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. Wee Hughie recalls a child’s first day of school and describes the poignant emotions both parent and child experience at this important milestone. The Wee Boy in Bed is a trip down memory lane, recalling childhood and little details etched into his brain like the lamp, the loom and granny comforting him by saying endearingly, “Och, whist ye ara-a-thais-ce” meaning “well then, O treasure.” The one thing he can’t remember is when his older siblings came to bed since he was then long asleep. The next generation of lovers is on their way!

Notes and translations, © Tanya Blaich, 2020

Paula Murrihy

Internationally acclaimed Irish mezzo-soprano Paula Murrihy is a regular guest at the world’s major opera houses and concert halls performing a wide variety of repertoire. Previously a member of the Ensemble at the Oper Frankfurt, Paula’s roles have included creating the title role Carmen in Barry Kosky’s iconic production, Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier, Dido in Dido and Aeneas, title role Pénélope, Fauré and Polissena in Radamisto. Highlights have also included Stéphano in Roméo et Juliette at the Metropolitan Opera, Ruggiero in Alcina for Santa Fe Opera, Concepción in L’Heure Espagnole for the Opernhaus Zürich, Frances, Countess of Essex in Gloriana for Teatro Real, Madrid and Idamante in Idomeneo for Salzburg Festival.

On the concert platform Paula enjoys a close relationship with MusicAeterna and Teodor Currentzis, with performances including Cosi fan tutte, Le nozze di Figaro, Purcell’s Indian Queen, Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, Hindemith’s Die Junge Magd and Des Knaben Wunderhorn at the Mariinsky Theatre and on a tour of Europe. She made her debut at the BBC Proms in 2016 in Haydn’s Paukenmesse, in 2018 she joined the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment for a European Tour of Bach’s St Matthew Passion under the direction of Mark Padmore and in 2019 debuted with the Britten Sinfonia and Sir Mark Elder for performances of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. An accomplished recitalist, Paula has given performances at the Wigmore Hall together with Malcolm Martineau, Aldeburgh Festival, the International Lied Festival Zeist, and Diaghilev Festival in Perm together with frequent collaborator and friend Tanya Blaich.

Paula is an alumna of DIT Conservatory of Music and Drama, Dublin and New England Conservatory, Boston.

Tanya Blaich

Tanya Blaich is a pianist and teacher with particular sensitivity for and expertise in the song and collaborative piano repertoire. A faculty member of New England Conservatory’s collaborative piano and voice departments since 2006, Blaich is co-coordinator of NEC’s Liederabend Series and teaches classes dedicated to the performance of song repertoire and in language diction and expression.

Blaich has performed in concert venues and festivals throughout the United States, Europe, and Russia with such recitalists as Thomas Hampson, Paula Murrihy, Klemens Sander, and Sari Gruber. Recent highlights with Murrihy include recitals at Teodor Currentzis’ International Diaghilev Festival, Performance Santa Fe’s Festival of Song, and in concert venues across Europe. She also worked with Murrihy and composer John Harbison in preparation for the world premiere of Harbison’s Sixth Symphony with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

As a guest artist, Blaich has given song recitals and master classes at universities and colleges throughout the USA. In addition to her collaborations with singers, she has performed as a chamber music partner with members of the Colorado, Lydian, and Miro string quartets. She has also served as a coach and rehearsal pianist for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Handel and Haydn Society, and Odyssey Opera.

Tanya Blaich attended the University Paris-Sorbonne and graduated from Walla Walla College in Washington. She moved to Vienna to pursue her passion for the German Lied repertoire, earning a diploma in performance from the Vienna Conservatory in vocal accompaniment and chamber music. She subsequently earned both her M.M. and D.M.A. from New England Conservatory.