Artist Led, Creatively Driven

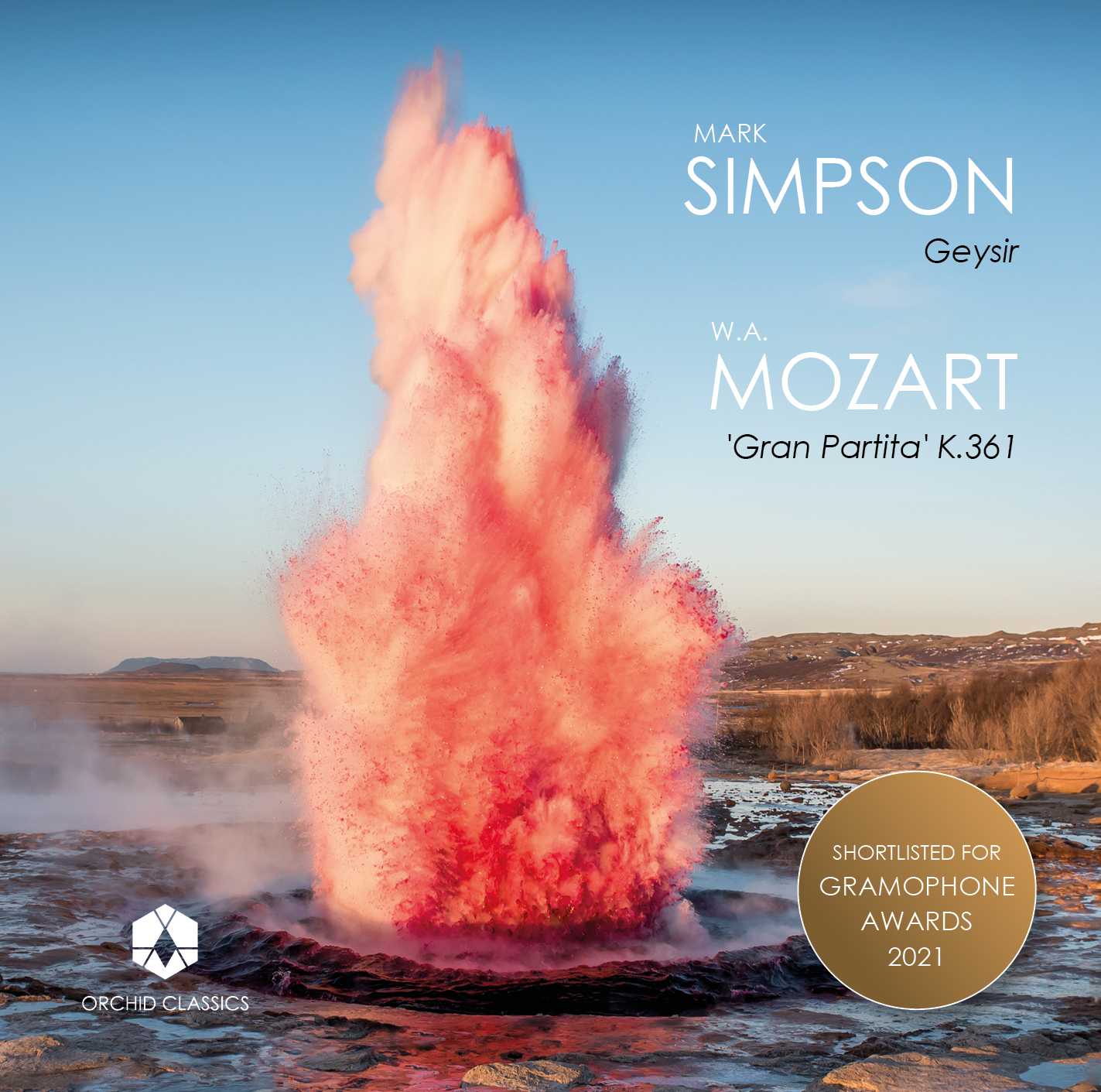

Mark Simpson

Geysir

Release Date: November 20th 2020

ORC100150

Mark Simpson (b.1988)

1 Geysir (world premiere recording) 7.55

W.A Mozart (1752-1796)

Serenade No.10, K.361 ‘Gran Partita’

2 I. Largo – Molto Allegro 9.24

3 II. Menuetto – Trio – Trio II 8.26

4 III. Adagio 5.06

5 IV. Menuetto – Allegretto – Trio – Trio II 4.48

6 V. Romanze: Adagio – Allegretto – Adagio 8.22

7 VI. Thema mit 6 Variationen – Andante 10.06

8 VII. Finale – Molto allegro 3.24

Total time 57.32

Mark Simpson, Fraser Langton, clarinet

Nicholas Daniel, Emma Feilding, oboe

Amy Harman, Dom Tyler, bassoon

Oliver Pashley, Ausiàs Garrigós Morant, basset horns

Ben Goldscheider, Angela Barnes, James Pillai, Fabian van de Geest, horns

David Stark, double bass

Mark Simpson, Geysir (2014)

Geysir was a commission for the Britten Sinfonia. It was imagined as a partner to Mozart’s Serenade in B flat (K.361), the ‘Gran Partita’, drawing on the same instrumental forces: pairs of oboes, clarinets, basset horns, bassoons, four horns, and double bass.

Geysir’s relationship to Mozart goes beyond programming convenience. Geysir – the Icelandic word for geyser, from the Old Norse geysa, ‘to gush’ – is the surface emanation of two ideas in the Serenade. The first is the resplendent B flat major chord that opens the ‘Gran Partita’: fulsome homophonic textures, making extravagant and atmospheric use of warm clarinets, basset horns, bassoons, and french horns, are key to the design of Simpson’s piece – though Geysir extends the spread and range of these chords to generate a sound world very much its own.

The second compositional seed comes from an especially numinous moment in Mozart: variation five of the Serenade’s sixth movement. A quartet of clarinets plays various iterations of a spread B flat major chord, pianissimo, with horns underneath; above this an oboe sings a plaintive and lightly-ornamented melody. These murmuring, overlapping figures are where Simpson finds the ‘bubbling’ clarinets at the outset of Geysir, and they shape its further melodic impulses. Texture itself is an idée fixe in Geysir, summoning a musical landscape that is organic, intuitive, even atavistic.

The title’s volcanic logic manifests in different ways. Its textural organisation combines a pulsing underlay of lugubrious French and basset horns, thickened by oozing bassoons and double bass, with lyrical eruptions from pairs of clarinets and oboes. The denser lower registers of the piece slacken and quicken across uneven syncopated rhythms like flows of magma or shifting tectonic plates, supplying energy for outbursts from clarinets and oboes above, as if a superheated column of steam and ash has breached the surface of the musical crust.

This is evident in the most intensely pressurised climax. The accompanying lower instruments pulse faster and surge upwards into loud blocks of sound that cover the ensemble’s entire range, cracking open to allow a screaming oboe through, like an old-fashioned kettle at a furious boil; the work’s tremors gradually subside and the lower instruments cool to a more dormant state, the piece ending more or less as it began. Simpson’s instrumental ensemble itself represents another canny link between title and timbre. Clarinets, oboes, and horns have a similar mechanism to volcanic eruptions themselves, as pressurised air is forced through narrow pathways to expel sound, breath, and moisture, in ways that can be explosive, spectacular, sinuous, or languid.

Inside Geysir

Mark Simpson in conversation with Benjamin Poore

Benjamin Poore: How did you write Geysir?

Mark Simpson: It was conceived as a companion piece to the ‘Gran Partita’. Initially I had wanted to explore the ensemble by dividing it into two symmetrical groups of six – an oboe, clarinet, basset horn, bassoon, and two horns – with the double bass at the centre and using that as a basis for a piece with palindromic structure. I gave up on this idea after some time working through it. I relistened to the ‘Gran Partita’ in an attempt to provide a new direction for the piece and it was the sensuousness of the instrumental writing and the sheer sound of the ensemble that eventually provided the springboard into a creative flow.

BP: How did the piece come together out of that?

MS: I took two very basic textural ideas from the Mozart as a starting point: the glorious B flat major homophonic chord at the outset of the piece, and the ‘bubbling’ clarinet parts in variation five of the Serenade’s sixth movement. Gradually it opened up and ended up being a flurry of colour and harmonic shifts.

BP: You dedicated Geysir to the composer Simon Holt. What’s his relationship to the work?

MS: Simon is someone whose music means a great deal to me – I conducted a piece of his whilst I was a student for oboe and ensemble, called Sparrow Night. I’ve played quite a lot of his clarinet music and later he wrote a basset clarinet concerto for me, Joy Beast, which I performed with the BBC Philharmonic. I just wanted to show him some gratitude, from one composer to another.

BP: What are the challenges of writing for an ensemble like this?

MS: I’m a wind player, so it was an instinctive thing – it never felt like trying to overcome any limitations. By the time I’d written the piece I’d played and directed the ‘Gran Partita’ several times. I remember that I really wanted to showcase the horns as they don’t get that much to do in the Mozart. I’d not written for basset horns before, and when I was re-listening to the ‘Gran Partita’ I wanted to try and use them in a more soloistic way.

BP: You began work on the piece in 2013. How does it look to you now?

MS: Normally after I’ve written something I just want to leave it for a while and have nothing to do with it, perhaps if I don’t feel like I’ve succeeded in getting it to where I want it to be. But I don’t think I feel that way about this piece. I’m very proud of it – I think it sits well alongside the Mozart. It has an expressive depth and a virtuosity of colour. The ‘Gran Partita’ gets performed so much these days – just search on YouTube for performances of it – and I’d love to see Geysir joining it on the concert platform more often.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Serenade in B flat, K.361/370a (1781-82)

At the finale of Mozart’s Don Giovanni a small wind band takes to the stage – clarinets, oboes, bassoons, and horns – to serenade the Don’s supper. “Voi suonate amici, cari…io mi voglio divertir!” he says to the musicians: “Strike up and play, friends! I want to be entertained!” They perform arrangements of operatic arias, not least ‘Non piu andrai’ from Le Nozze di Figaro; “Not this again”, Leporello sighs.

This kind of Tafelmusik led Mozart’s contemporary Immanuel Kant to rate music as the lowest of the arts, unsure as to whether it can ever be more than merely agreeable. In Don Giovanni such music is the backdrop for the Don’s unseemly hunger as he munches his pheasant – “Ah che barbaro appetito!”, remarks Leporello. The musicians aren’t condemned to the flames with the titular anti-hero, but they are still stitched into the fabric of this dissolute, decadent world: musical light entertainment tarnished by moral turpitude.

How perplexing, perhaps, that the tradition of ‘Harmonie’ music sent up in Don Giovanni is the one that generated a masterpiece like the ‘Gran Partita’ Serenade. In characteristically effortless Mozartean fashion it is a work whose achievement is to summarise, perfect, and exceed the musical context that made it.

With its two minuets and celebratory finale the Serenade in B flat evidently belongs to a tradition of dance suites played by wind bands for the entertainment of aristocrats, whether at supper or wedding celebration. (A notion persists that it was composed for Mozart’s own marriage to Constanza.) But its expanded instrumental forces and scale make it much more than pleasant, relaxing background music, and see Mozart making a powerful expressive claim of his own in this medium. That its first documented performance took place in a concert hall – a benefit for clarinettist Anton Stadler – is a keen sign of the ‘Gran Partita’ stepping beyond its generic and artistic bounds.

As a compositional tour de force – comprising a set of variations, a sonata-form first movement, multiple ‘trio’ sections in the dances, and Rondo finale – it goes well beyond the mere arrangements of popular operatic numbers lampooned in Don Giovanni, a key part of the Harmonie ensemble’s day job. Of course Mozart himself would arrange numbers from his 1782 success Die Entführung aus dem Serail for wind ensemble, and it’s not hard to imagine the final burlesque of the Serenade embellished with a hit of ‘Janissary’ percussion. The ‘Gran Partita’ is a work that pivots between convention and invention.

This early 1780s saw Mozart particularly committed to writing for woodwinds. The ‘Gran Partita’ certainly relishes in the clarinet sounds available to him in Vienna that were absent in Salzburg, especially given the talents of the Stadler brothers; for the premiere of Die Entführung Mozart assembled a crack team of woodwind players for its vibrant score. Chamber works like the Serenade in C minor (K388) and the Oboe Quartet (K370) are notable examples, but so too in other works of the period did woodwind instruments become important musical protagonists in their own right, particularly in his piano concertos in G (K453) and in B flat (K456). 1781’s revolutionary Idomeneo would make extravagant and vivid use of a full woodwind section, such as in the concluding ballet, Act II March, or the titular character’s final aria ‘Torna la pace al core’.

Much has been written about what makes the ‘Gran Partita’ so miraculous. Its structural sophistication and formal variety is certainly key, alongside an intuitive melodic sensibility. But Mozart’s meticulous exploration of the textures and timbres possible in his wind ensemble is at the heart of this work too.

The Adagio – described exultingly by Salieri in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus – is an exquisite example. The opening bar of horns and bassoons, playing in octaves and in unison, is sumptuous but restrained; this richness grows and glows as clarinet and basset horn enter with pulsing semiquavers in the next bar. It is itself offset by the piquancy of the high oboe melody that joins the ensemble in bar four, finally smoothed out and softened by the more muted clarinet sound that takes up melodic responsibility a few beats later.

In expanding the second movement’s structure to include an additional trio section Mozart creates space for reflection and contrast, and there we see this fastidious working out of textural possibility too. In Trio I Mozart restricts himself to the warm and mellow sonorities of his single-reed basset horns and clarinets; in Trio II the darker harmonic turn into G minor is marked by the entry of the double-reeds of the ensemble, with pungent bassoon triplets and keening oboes.

The work constantly examines contrasting sonorities – pairs of clarinets and oboes, thick textures against spare ones, homophony versus counterpoint – with the care and thoroughness of an eighteenth-century polymath discovering the spectrum of visible light. Mozart is hardly avant-garde here. But Mozart’s subtleties in shading and timbre seem to presage, for instance in the Romanza’s opening bars, the kind of Klangfarbenmelodie pioneered by the Second Viennese School over a century later, showcasing the futurity of this music’s imaginative world.

© Benjamin Poore

Mark Simpson

Composer and clarinettist Mark Simpson (b.1988, Liverpool) became the first ever winner of both the BBC Young Musician of the Year and BBC Proms/Guardian Young Composer of the Year competitions in 2006. He went on to read Music at St. Catherine’s College, Oxford, and studied composition with Julian Anderson at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, before being selected for representation by the Young Classical Artists Trust. Simpson was a BBC New Generation Artist from 2012-2014. He received a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Fellowship in 2014 and the Royal Philharmonic Society Composition Award in 2010, and was a Visiting Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. In 2015 he was appointed Composer in Association of the BBC Philharmonic for a period of four years.

Simpson’s The Immortal (2015), an oratorio for baritone, chorus and symphony orchestra, was premiered by the BBC Philharmonic and Juanjo Mena at the Manchester International Festival, with support from Sky Arts Futures Fund and IdeasTap, receiving immediate critical acclaim: ‘blazingly original’ (The Guardian); ‘the best new choral work I’ve heard in years’ (The Times). Other orchestral works include Israfel (2014), premiered by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and Andrew Litton, sparks (2012), commissioned for the Last Night of the Proms and A mirror-fragment… (2008), written for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

Highlights of 2016 included the premiere of Simpson’s first opera Pleasure, with a libretto by Melanie Challenger, commissioned by Opera North, the Royal Opera and Aldeburgh Music with performances in Leeds, Liverpool, Aldeburgh and London. Simpson also premiered Hommage à Kurtág for clarinet, piano and viola with Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Antoine Tamestit, commissioned by the Salzburg and Edinburgh International festivals. He also gave the online premiere of Darkness Moves for solo clarinet, commissioned by the Borletti-Buitoni Trust. Under his Composer in Association role with the BBC Philharmonic Simpson has composed a Cello Concerto for Leonard Elschenbroich in 2018 and a Clarinet Concerto for himself as soloist in 2019.

Simpson performs widely as a soloist and chamber musician and is hugely committed to the performance of new music. He performed and recorded the Lindberg Clarinet Concerto with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Adams’s Gnarly Buttons with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and has given many solo performances including with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Vasily Petrenko), Northern Sinfonia (Yan Pascal Tortelier), BBC Philharmonic (Gianandrea Noseda), City of London Sinfonia and BBC Concert Orchestra. He has played recitals at Wigmore Hall, Royal Festival Hall, Sage Gateshead, Cheltenham Festival, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, BeethovenFest, O’Modernt and Trasimeno Festivals, with premieres of works by Simon Holt, Jonathan Harvey and Edmund Finnis.

Simpson performed Magnus Lindberg’s Clarinet Concerto with the BBC Philharmonic and HK Gruber in February 2016 and was invited to play the concerto again in Salzburg in November of the same year and at the 2018 BBC Proms with Juanjo Mena. During summer 2016 he made his debut at the Edinburgh and Salzburg festivals in a trio programme of Schumann and Kurtág, alongside his own new work, with Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Antoine Tamestit. In 2019 he was composer in residence at the Leicester International Music Festival, who co-commissioned his Oboe Quartet for oboist Nicholas Daniel, and in 2020 he is featured composer at the Trondheim Chamber Music Festival, the first major feature of his music in Norway. Simpson is currently working on a Violin Concerto for Nicola Benedetti with commissioners including the London Symphony Orchestra, WDR Sinfonieorchester and Royal Scottish National Orchestra.

Recording of the Year Winner

Presto Music

Ten Best Classical Events of 2020

The Observer

“This ad hoc group’s Mozart playing is buoyant, nimble, expansive, elegant, witty and muscular… Each detail, accent or ornament, is precise and purposeful. It’s gone straight on to my best albums of the year list.”

Fiona Maddocks, The Observer

“Brave is the composer who would venture a companion piece to Mozart’s Serenade K361… Mark Simpson isn’t just brave. He has also triumphed.”

BBC Music Magazine

“[Geysire is] a fascinating, accessible work, an ideal curtain raiser for the Mozart Serenade.”

The Arts Desk

“Each listening reveals new interesting features missed before; this is contemporary music that wind ensembles should make part of their regular repertoire.”

The Classic Review

“this is a fresh and absorbing album of its type, well worth the attention of anyone…”

AllMusic