Artist Led, Creatively Driven

VOICE OF RACHMANINOFF

John-Henry Crawford, cello

Victor Santiago Asuncion, piano

Release Date: 9th June

ORC100241

VOICE OF RACHMANINOFF

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Morceaux de Fantasie, Op.3

1. No.1 Elégie – Moderato

12 Romances, Op.21 No.7

2. Zdes Khorosho “How fair this spot”

6 Songs, Op.4 No.4

3. Ne poy krasavitsa pri mne “Oh never sing to me again”

Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, Op.43

4. Var XVIII – Andante Cantabile

Sonata for Cello and Piano in G Minor, Op.19

5. I Lento – Allegro Moderato

6. II Allegro scherzando

7. III Andante

8. IV Allegro Mosso

9. Vocalise, Op. 34 No.14

10. “Preghiera”

Arranged by Fritz Kreisler & Shelbie Rassler from

Piano Concerto No.2 in C Minor, Op.18 2nd movement

John-Henry Crawford, cello

Victor Santiago Asuncion, piano

Rachmaninoff is most revered as a pianist and for his magnificent compositions for the instrument, but he also had a remarkable ability to sing through the soaring melodies one finds across his entire musical output.

This album celebrating his one hundred and fiftieth anniversary displays not only the power and richness of his piano writing, but also his extremely vocal style. His romances for voice like “How fair this spot” and “Oh never sing to me again” show his heart on his sleeve while his Vocalise magnifies the human voice to an almost total purity, devoid of any given syllables or words.

Also in this programme are transcriptions from his solo piano literature which highlight the singing nature of his orchestral melodies. From the slow movement of his second piano concerto in the seemingly infinite lines of the winds and strings, the yearning Elegie adapted from his Morceaux de Fantasie, to the eighteenth variation of his Rhapsody for piano and orchestra which climbs to an ever-reaching climax.

The mainstay of the program is the Sonata in G Minor for Cello and Piano, which is the only sonata Rachmaninoff wrote for any solo instrument other than piano. Rachmaninoff had a great affection for the cello, not surprisingly given its likeness to the human voice. The Sonata boasts one song after another in a vast work with a devilishly difficult piano part, on par with that of his piano concerti. This collection of works shows Rachmaninoff at his most nostalgic and illustrates how adept he was at fusing pianistic brilliance with rich soulful lyricism.

John-Henry Crawford

Sergei Rachmaninoff began his studies at the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1883, aged only 10. He then transferred to the Moscow Conservatory, where he shared lodgings with his teacher, Nikolai Zverev, and other students. Surrounded by the constant din of piano practice, Rachmaninoff struggled to compose, and he was ejected after requesting more privacy. In a pattern that would recur throughout his career, Rachmaninoff retreated to the countryside to compose, finding the quiet and solitude much more conducive to creativity. Some of the music written at this time, in the 1890s, included several pieces for cello and piano, written for himself and the celebrated cellist Anatoly Brandukov. Brandukov was 14 years Rachmaninoff’s senior and a close friend; he went on to be best man at the composer’s wedding in 1902. Brandukov was also greatly admired by Tchaikovsky and performed many of his cello works – but whereas Tchaikovsky balked at combining the piano with stringed instruments owing to their different timbres, Rachmaninoff seems to have been quite at home with bringing these forces together.

Rachmaninoff’s first Prelude for solo piano, in C-sharp minor, dates from those early years; he composed the piece at the age of 19. He then wrote four pieces to add to the Prelude to create the suite Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3; he premiered the set on 27 December 1892, presenting Tchaikovsky with a newly published copy two months later. Tchaikovsky wrote to his former student and Rachmaninoff’s cousin Alexander Siloti singing the work’s praises. The first piece in the set is the Élégie in E-flat minor, which opens with a widely spaced, brooding piano texture over which, in this arrangement, the cello’s plaintive, song-like melody unfolds.

Rachmaninoff’s fourth set of songs, Op.21, was composed a decade later in 1902 (apart from the first song written in 1900). The pieces are striking for the way the piano writing reflects the texts; many of the piano parts act as studies on the poems. ‘How fair this spot’, Op.21 No.7, lends itself beautifully to the combination of cello and piano, the original poem by Glafira Galina painting a vivid picture of nature and the joys of solitude. The Six Songs, Op.4, were complete by 1893. A poignant tone characterises the fourth piece of the set, ‘Oh do not sing’, Pushkin’s poem expressing the very specific desolation of missing life in Georgia, transformed into a more universal sense of longing in the cello’s mournful lines and the piano’s aching harmonies.

Rachmaninoff composed his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op.43 in a burst of creativity between 3 July and 18 August 1934. Paganini’s Caprice No.24 has inspired numerous sets of variations, but Rachmaninoff’s is particularly sophisticated; he side-steps the purely episodic feel of variation form by giving the piece a concerto-like structure. Livelier outer sections frame the slower material at the heart of the work, specifically the luminous 18th variation – a gorgeously expansive, long-breathed melody based on an inversion of the original theme. Rachmaninoff himself recognised the popular potential of this melody, remarking: ‘This one is for my agent’.

The catastrophic premiere of Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony in 1897 hit him hard, and he suffered a nervous breakdown; it took several years and extensive psychotherapy for his mental health to rally. When the Piano Concerto No.2 was premiered to great acclaim, Rachmaninoff’s self-assurance grew, and this newfound confidence spurred him to compose his Sonata for Cello and Piano in G minor. The popularity of the concerto overshadowed the sonata, but it remains his most beloved chamber work. Both pieces bear many of Rachmaninoff’s most irresistible musical fingerprints: expansive melodic lines, aching nostalgia, and a sense of scope suggestive of the vast Russian landscape.

The Sonata – which turned out to be Rachmaninoff’s final chamber work – was completed in the winter of 1901, and was premiered on 2 December in Moscow by the work’s dedicatee, Brandukov, with the composer himself tackling the fiendish piano part. It seems likely that Rachmaninoff made some modifications after the work’s premiere, as he wrote ‘12 December 1901’ on the score.

The Sonata is perfumed with the incense of the Russian Orthodox Church; Rachmaninoff was profoundly influenced by the spacious sonorities of Russian choral music and by the sounds of bells. The expansive first movement opens with a Lento introduction, the cello intoning soulfully in the manner of a Russian Orthodox cantor, while the piano articulates a six-note figure that becomes integral to the work. An animated Allegro moderato follows, its second theme a quintessential example of Rachmaninoff’s lyricism.

The Allegro scherzando begins with vigorous energy before a fulsome melody blossoms from the movement’s earthy origins, with piano writing reminiscent of the Second and Third Piano Concertos. The beautiful Andante starts with the piano unfolding a melody of great tenderness, its ardent undercurrent accentuated by shifts between major and minor. The cello takes up the theme and the material undulates and grows, eventually building towards a passionate climax after which delicate piano writing leads us into the gentle final bars.

As with the second movement, the finale features strong contrasts between the lively and the lyrical. There are striking colouristic effects in a dazzling array of piano sonorities, sometimes in counterpoint with the cello’s flowing lines. Rachmaninoff ties the whole work together by alluding to the first movement and to the six-note idea first articulated there, and there is one last moment of yearning romance before a swift and brilliant conclusion.

The Vocalise, Op.34, No.14 (1915), is the last of Rachmaninoff’s 14 Songs. Unusually, the original song has no text; Rachmaninoff treats the voice like an instrument, with the vocalist allowed to choose a vowel sound through which to articulate the song’s imploring melody. Inevitably, this has led to a number of instrumental versions, the most famous of which is this arrangement for cello and piano.

Writing in Moscow newspaper Russkiye Vedomosti, Joel Engel argued that: “The symphonic and chamber music of Russia is … in strong, trustworthy hands. Here Rachmaninoff is in the front rank. It is sufficient to recall his last three important works to convince oneself of this – the Second Symphony, the Second Piano Concerto, and the Cello Sonata. Each was an event in its field, each evidenced the growth of Rachmaninoff’s talent, and each broadened the circle of this talent’s admirers.” The achingly beautiful slow movement of the Piano Concerto No.2 in C minor, Op.18, shows the influence of Tchaikovsky. One of Rachmaninoff’s greatest achievements, the movement inspired this chamber-scale arrangement, Preghiera (Prayer) by the great violinist-composer Fritz Kreisler – who made several violin sonata recordings with Rachmaninoff at the piano.

© Joanna Wyld, 2023

John-Henry Crawford

Cello

Louisiana born cellist John-Henry Crawford has been lauded for his “polished charisma” and “singing sound” (Philadelphia Inquirer). In 2019, he won First Prize in the IX International Carlos Prieto Cello Competition and was named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation, and in 2021, he was shortly after named the National Federation of Music Clubs’ 2021-2023 Young Artist in Strings.

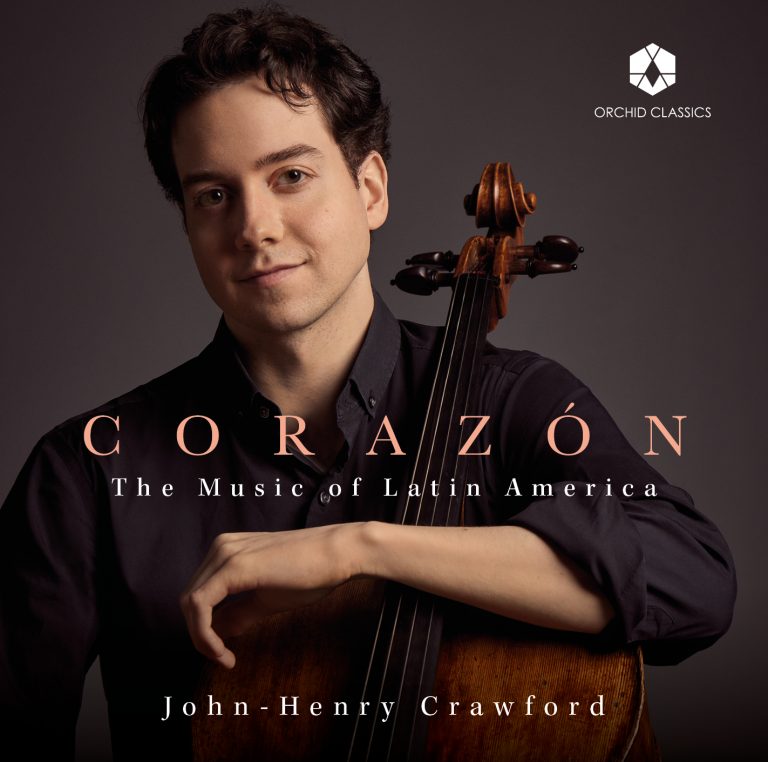

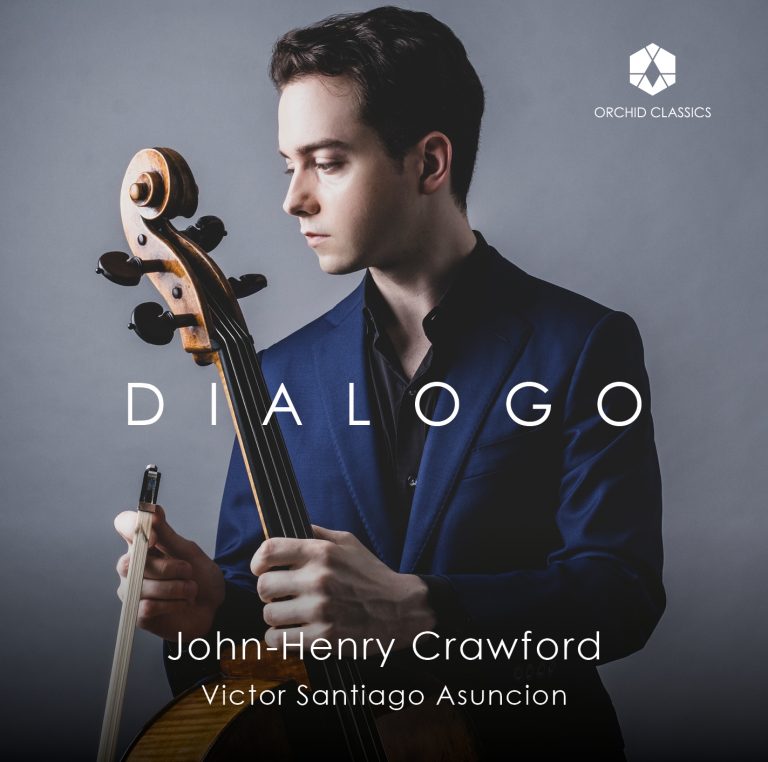

His most recent album, Corazón: The Music of Latin America (Orchid Classics – June 2022) was selected as Editor’s choice in Gramophone Magazine and was #5 on the Billboard Classical Charts in its first week. Crawford’s debut album Dialogo (Orchid Classics – June 2021) appeared on the Billboard Top 10 chart as well as the top 5 on iTunes and #1 on Amazon’s Classical New Releases. Gramophone Magazine wrote, “There’s such a rich variety of colour, touch and texture, and as much vulnerability as dramatic intensity… A splendidly satisfying recital on all counts,” while The Strad claimed, “The clean, close recording is like seeing everything through a very powerful lens… a striking interpretation.”

Crawford commands a strong Instagram presence, having attracted tens of thousands of viewers to his project #The1000DayJourney, where he films artistic cinematic videos daily from his practice and performances for over 50,000 followers (@cellocrawford) to give a glimpse into the working process of a musician.

At age 15, Crawford was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music to study with Peter Wiley and Carter Brey. He continued to complete a Master of Music at The Juilliard School with Joel Krosnick, an Artist Diploma at the Manhattan School of Music with Philippe Muller. Other equally important musical mentors have been such artists of note as Lynn Harrell, Zuill Bailey, Andres Diaz and Hans Jorgen Jensen. He has given concerts in 25 states as well as Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Mexico, and Switzerland at venues such as The International Concert Series of the Louvre in Paris, Volkswagen’s Die Gläsern Manufaktur in Dresden. Crawford gave his solo debut with The Philadelphia Orchestra as First Prize Winner of the orchestra’s Greenfield Competition.

Crawford’s numerous competition prizes also include Grand Prize and First Prize Cellist at the 2015 American String Teachers National Solo Competition, the Lynn Harrell Competition of the Dallas Symphony, the Hudson Valley Competition, and the Kingsville International Competition.

He has been a fellow at the Verbier Festival Academy, Music@Menlo, the Perlman Chamber Music Program, Music from Angel Fire in New Mexico, the National Arts Centre’s Zukerman Young Artist Program in Canada, and The Fontainebleau School in France.

Crawford is from a musical family and performs on a rare 200-year-old European cello smuggled out of Austria by his grandfather, Dr. Robert Popper, who evaded Kristallnacht in 1938 and a fine French bow by the revolutionary bowmaker Tourte “L’Ainé” from 1790. In addition to music, he enjoys learning languages, performing magic tricks, and photography.

Learn more at www.johnhenrycrawford.com

Victor Santiago Asuncion

Piano

Hailed by The Washington Post for his “poised and imaginative playing,” Filipino-American pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion has appeared in concert halls in Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, Spain, Turkey and the USA, as a recitalist and concerto soloist. He played his orchestral debut at the age of 18 with the Manila Chamber Orchestra, and his New York recital debut in Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall in 1999. In addition, he has worked with conductors including Sergio Esmilla, Enrique Batiz, Mei Ann Chen, Zeev Dorman, Arthur Weisberg, Corrick Brown, David Loebel, Leon Fleisher, Michael Stern, Jordan Tang, and Bobby McFerrin.

A chamber music enthusiast, he has performed with artists such as Lynn Harrell, Zuill Bailey, Andres Diaz, James Dunham, Antonio Meneses, Joshua Roman, Cho-Liang Lin, Giora Schmidt, the Dover, Emerson, Serafin, Sao Paulo, and Vega String Quartets. He was on the chamber music faculty of the Aspen Music Festival, and the Garth Newel Summer Music Festival. He was also the pianist for the Garth Newel Piano Quartet for three seasons. Festival appearances include the Amelia Island, Highland-Cashiers, Music in the Vineyards, and Santa Fe.

His recordings include the complete Sonatas of L. van Beethoven with cellist Tobias Werner, Sonatas by Shostakovich and Rachmaninoff with cellist Joseph Johnson, the Rachmaninoff Sonata with the cellist Evan Drachman, and the Chopin and Grieg Sonatas, also with cellist Evan Drachman. He is featured in the award-winning recording “Songs My Father Taught Me” with Lynn Harrell, produced by Louise Frank and WFMT-Chicago. Mr. Asuncion is the Founder, and Artistic and Board Director of FilAm Music Foundation, a non-profit foundation that is dedicated to promoting Filipino classical musicians through scholarship, and performance.

He received his Doctor of Musical Arts Degree in 2007 from the University of Maryland at College Park under the tutelage of Rita Sloan. Victor Santiago Asuncion is a Steinway artist.