Artist Led, Creatively Driven

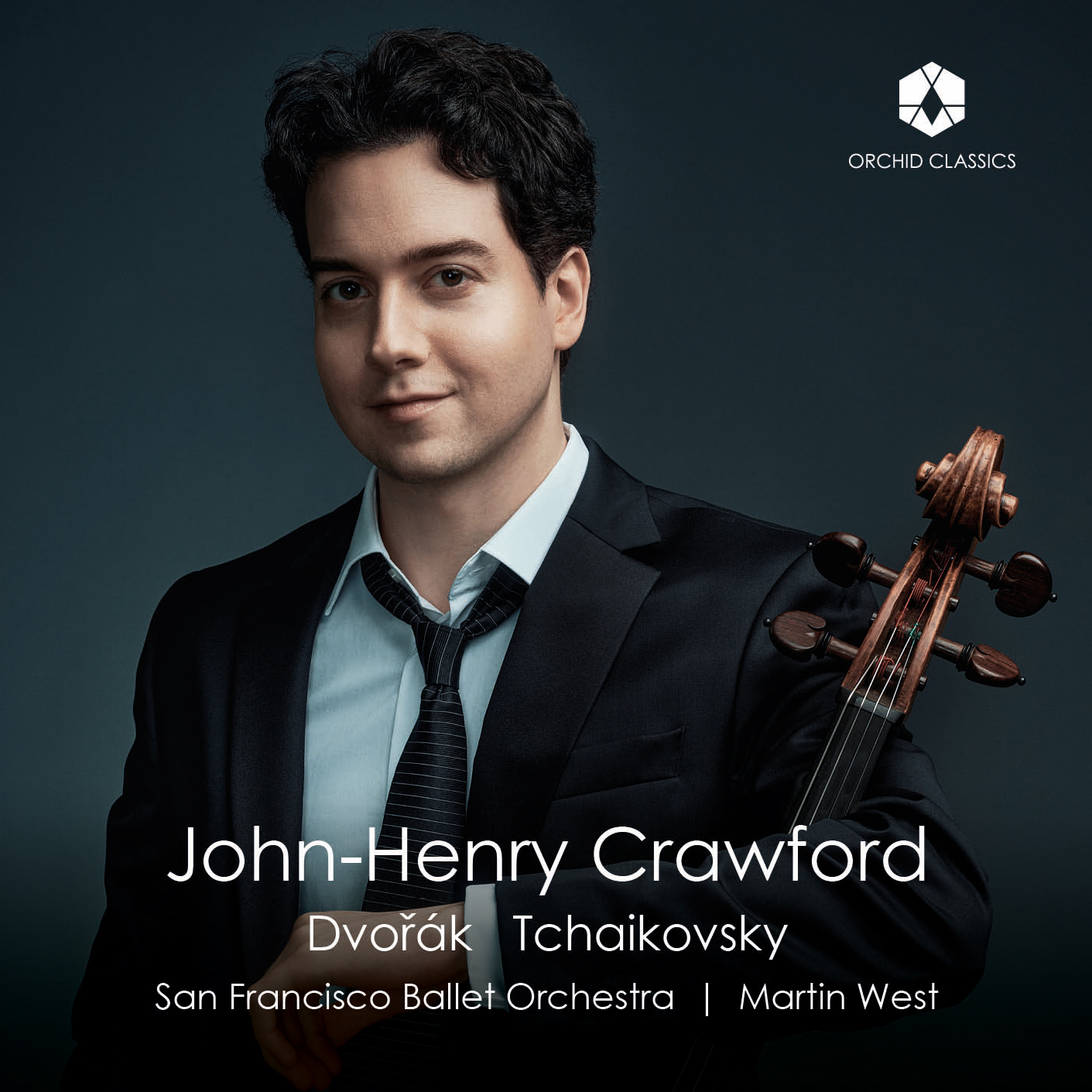

Dvořák | Tchaikovsky

John-Henry Crawford, cello

San Francisco Ballet

Orchestra Martin West, conductor

Release Date: June 28th

ORC100292

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33, TH. 57

1. Moderato assai quasi Andante Thema: Moderato semplice

2. Var. I: Tempo della Thema

3. Var. II: Tempo della Thema

4. Var. III: Andante Sostenuto

5. Var. IV: Andante grazioso

6. Var. V: Allegro moderato

7. Var. VI: Andante

8. Var. VII e Coda: Allegro Vivo

Antonin Dvorak (1841–1904)

Concerto in B Minor for cello and orchestra, Op. 104

9. Allegro

10. Adagio, ma non troppo

11. Finale: Allegro moderato

John-Henry Crawford, cello

San Francisco Ballet

Orchestra Martin West, conductor

This album brings together two large-scale works shaped by the close association of a composer and a virtuoso cellist. Neither Tchaikovsky nor Dvořák played the cello (though Dvořák led the viola section of the Prague Provisional Theatre Orchestra as a young man); but each collaborated with high-level performers. And both Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations and Dvořák’s Cello Concerto bear dedications to the players who were to give their premieres – though in neither case did this quite work out as originally planned.

Tchaikovsky composed his Rococo Variations in the winter of 1876. He was thirty-six years old, had recently finished his ballet Swan Lake, and was beginning to correspond with the wealthy widow Nadezhda von Meck who would rapidly become a crucial confidante and financial support over the next decade.

He was, in other words, an established musician in Moscow musical life. Within the great circle of professional musicians that populated the city, he was already familiar with the German cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen (1848-90): indeed, Fitzenhagen had been involved in the premieres of several of Tchaikovsky’s chamber compositions of the earlier 1870s.

The very title of the Rococo Variations points to Tchaikovsky’s love of eighteenth- century music, a theme and variation set is also firmly in keeping with the style of his models. Eight variations followed, varying in tempo and mood, ending with

a sprightly dancing finale and coda. So far, so good. But Tchaikovsky not only dedicated the work to Fitzenhagen: he also allowed him to make alterations to ‘improve’ the finished product. Had this simply been a question of tidying up

the cello part to make it more idiomatic, there would be little more to say. But

Fitzenhagen was far more interventionist. He made serious changes and cuts,

required Tchaikovsky to add repeats, reorder material and even delete one

variation altogether. (The deletion and reordering, in combination, was evidently designed to bring an audience to its feet: Fitzenhagen wrote to Tchaikovsky after performing the piece in Germany in 1879 that the effect of his alterations was so impressive that Franz Liszt had remarked to him afterwards, ‘You carried me away!’).

Tchaikovsky was clearly not comfortable with these multiple changes, but for whatever reason felt unable, or unwilling, to contradict his supremely confident soloist. His publisher Pyotr Ivanovich Jürgenson was much less understanding. ‘Loathsome Fitzenhagen!,’ he raged to the composer in 1878. ‘He is most importunate in wishing to alter your cello piece, to make it more suitable for the instrument, and he says you have given him full authority to do this. Good heavens!’ But it is only in the late 1880s that we find Tchaikovsky himself voicing his frustration and disappointment with the final state of the Variations, and by then it was too late. Fitzenhagen had published an edition of the work which became – and remains – the standard text, as we hear it here.

Tchaikovsky’s introduction and theme are a deft blend of gestures familiar from the works of Mozart, Haydn and others, with the harmonic quirks and orchestral palette which marks them unmistakeably as the composer’s own. Seven variations now follow, which also draw on Classical variation practice: dancing solo figurations, conversational exchanges between soloist and ensemble. The wistful third variation Andante and the spinning, balletic trills of the fifth variation are less disguisedly Tchaikovskian, as is the mournful waltz in the sixth; but the frequent pauses for showy mini-cadenzas, as well as the placement and shape of the rip- roaring conclusion (the original finale is entirely missing), is down to Fitzenhagen.

What are we to make of this oddly patchwork composition? Rather than

joining Jürgenson’s fist-shaking at Fitzenhagen, it’s perhaps more interesting to consider that ‘final’ versions of compositions are almost never the result of just a single creator. Composers don’t work in a vacuum: they take encouragement, advice, the suggestion of musicians or critics, or respond to financial or political factors in order to bring a piece to the concert platform. In the Rococo Variations we meet a Tchaikovsky who is above all pragmatic – even against his better judgement – and can eavesdrop on the results of a composer and soloist sharing artistic agency in the creation of a final version.

Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor was also linked in the composer’s mind with a particular player: the Czech performer and pedagogue Hanuš Wihan, who had been a good friend for some years and who received its dedication. But Wihan was not the cellist to premiere the Concerto. That honour fell to the British musician Leo Stern.

Dvořák had begun work on the Concerto in the United States of America,

in 1894, inspired by a similar work by the American composer-cellist Victor Herbert. He finished a draft in a few months, but the final revised score was only completed in April 1895. The premiere was offered to the Philharmonic Society in London, an organisation – and a city – with which he had a long-standing and fruitful association. Unfortunately, there were complications. Wihan, who was the cellist of the renowned Bohemian Quartet, was unavailable on the date that the Society planned to hold the concert. Although Dvořák insisted that this meant the programme must be changed – ‘I have promised to me friend Wihan – he will play it’ – the Society pushed back. The concert had already been advertised, complete with details of the programme: it was too late to back out now. Another cellist, Leo Stern, had been booked in Wihan’s stead.

Thanks to intensive study with the composer, it seems that Stern did a fine job, and the work was warmly received. It’s easy to see why: the outer movements are by turn highly dramatic and intensely lyrical, the impassioned orchestral introduction giving way to moments of melting intimacy and fleet-footed figuration from the soloist. The gently classicising, song-like central Adagio is almost improvisatory in its gradual unfolding and development of its opening melody, whilst the finale struts along with great verve and grace. And Dvořák was evidently very pleased with this Concerto – which was, to the last note, all his Concerto: ‘I must insist that my work be published just as I have written it.’

John-Henry Crawford

Cello

Born in Shreveport, Louisiana, cellist John-Henry Crawford has been lauded for his “polished charisma” and “singing sound” (Philadelphia Inquirer). In 2019, he won First Prize in the IX International Carlos Prieto Cello Competition and was named Young Artist of the Year by the Classical Recording Foundation, and in 2021, he was named the National Federation of Music Clubs’ 2021-2023 Young Artist in Strings. In 2023 he made his Carnegie Hall debut as the inaugural recipient of the American Recital Debut Award. Some notable 2024 events are a debut at the Sociedad Filarmonia in Gran Canaria, Spain’s first and oldest standing concert series, the El Paso Pro Musica, guest artist and professor at the Festival Internacional de Violoncello in Mexico, as well as appointment as the Artistic Director of the Violoncello Society of New York’s professional ensemble.

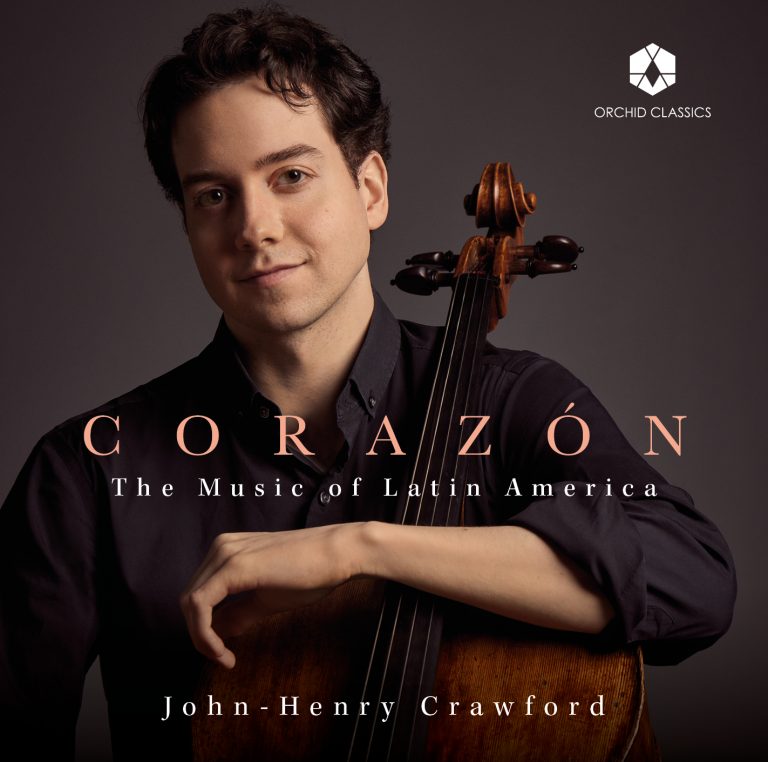

His albums with Steinway pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion have accrued over 3 million streams. Corazón: The Music of Latin America (Orchid Classics – June 2022) reached #5 on the Billboard Classical Charts in its first week and was selected as Editor’s choice in Gramophone Magazine. Crawford’s debut album Dialogo (Orchid Classics – June 2021) as well as his most recent release Voice of Rachmaninoff (Orchid Classics – June 2023) appeared on the Billboard Top 10 Classical chart. Gramophone Magazine wrote, “There’s such a rich variety of colour, touch and texture, and as much vulnerability as dramatic intensity… A splendidly satisfying recital on all counts,”

At age 15, Crawford was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music, later completing a Master of Music at The Juilliard School, and an Artist Diploma at the Manhattan School of Music. Other major mentors have been cellists such as Lynn Harrell, Hans Jorgen Jensen, Zuill Bailey, and Andres Diaz. He has given concerts in 25 states as well as Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, France, Germany, Mexico, and Switzerland at venues such as The International Concert Series of the Louvre in Paris, Volkswagen’s Die Gläsern Manufaktur in Dresden. Crawford gave his concerto debut with The Philadelphia Orchestra as First Prize Winner of the orchestra’s Greenfield Competition.

Crawford commands a strong Instagram presence, attracting tens of thousands of viewers to his project #The1000DayJourney, where for 3 years he filmed artistic cinematic videos daily from his practice and performances for over 50,000 followers (@cellocrawford) to give a glimpse into the working process of a musician.

Crawford’s numerous competition prizes also include Grand Prize and First Prize Cellist at the 2015 American String Teachers National Solo Competition, the Lynn Harrell Competition of the Dallas Symphony, the Hudson Valley Competition, and the Kingsville International Competition. He has competed in the Tchaikovsky and Queen Elisabeth competitions and was accepted at the prestigious Verbier Academy in Switzerland. John-Henry Crawford has also been a fellow at Music@Menlo, the Perlman Chamber Music Program, Music from Angel Fire in New Mexico, the National Arts Centre’s Zukerman Young Artist Program in Canada, and The Fontainebleau School in France.

Crawford is from a musical family and performs on a rare 200-year old European cello smuggled out of Austria by his grandfather, Dr. Robert Popper, who evaded Kristallnacht in 1938 and a fine French bow by the revolutionary bowmaker Tourte “L’Ainé” from 1790. In addition to music, he enjoys learning languages, performing magic tricks, and photography.

Learn more at www.johnhenrycrawford.com.

San Francisco Ballet Orchestra

Under the direction of Music Director and Principal Conductor Martin West, San Francisco Ballet Orchestra is internationally recognized as one of the foremost ballet orchestras in the world. After decades of using freelance musicians, the Orchestra was founded in 1975—as Performing Arts Orchestra—under Music Director Denis de Coteau. The Orchestra performs all of San Francisco Ballet’s repertory programs at the War Memorial Opera House, and has accompanied other companies including Hamburg Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet, American Ballet Theater, Bolshoi Ballet, and The Royal Ballet. The Orchestra has established a critically acclaimed discography of 21 recordings, beginning with Paul Chihara’s The Tempest in 1982. In 2015, the Orchestra won two Grammy awards in the classical music category for Ask Your Mama, composer Laura Karpman’s setting of Langston Hughes’ poem “Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz.” The Orchestra has appeared in televised recordings such as the inaugural Lincoln Center at the Movies: Great American Dance broadcast of previous SF Ballet Artistic Director Helgi Tomasson’s Romeo & Juliet, and PBS’s Great Performances: Dance in America broadcasts of John Neumeier’s The Little Mermaid, Lar Lubovitch’s Othello, Tomasson’s Nutcracker, and former Co-Artistic Director Michael Smuin’s productions of The Tempest, Cinderella, Romeo & Juliet, and A Song for Dead Warriors.

Martin West

Conductor

Martin West is acknowledged as one of the foremost conductors of ballet, garnering critical acclaim throughout the world. In 2005 he joined San Francisco Ballet as music director having been a frequent guest since his debut two years earlier He was previously principal conductor of English National Ballet and has worked with many of the top companies in North America such as New York City Ballet, Houston Ballet, and The National Ballet of Canada as well as The Royal Ballet in England and The Dutch National Ballet. He is also the founding music director of Ballet Sun Valley.

In his years as music director, West has been credited with raising the standard and profile of the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra to new levels and has made a number of critically acclaimed recordings with them, including the complete scores of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, and excerpts from Delibes’ Coppélia and Sylvia.. He and the Orchestra have also made many world premiere recordings; including music by composers such as Bizet, Moszkowski, Shinji Eshima and Maury Yeston. Their recording of Lowell Liebermann’s Frankenstein was recently release on Reference Recordings and their recording of C.F. Kip Winger’s Conversations With Nijinksy was nominated for a Grammy. In addition, West conducted on the award-winning DVD of John Neumeier’s The Little Mermaid as well as Helgi Tomasson’s productions of Nutcracker for PBS and Romeo & Juliet for Lincoln Center at the Movies: Great American Dance. During the Covid pandemic, West and the orchestra managed to create a number of recordings for the SF Ballet digital season, including the entire 30 min score for the world premiere of Wooden Dimes – recorded individually at home by the players and compiled and edited together by West.

Born in Bolton, England, he studied math at St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge University, before studying at the St. Petersburg Conservatory of Music and London’s Royal Academy of Music.