Artist Led, Creatively Driven

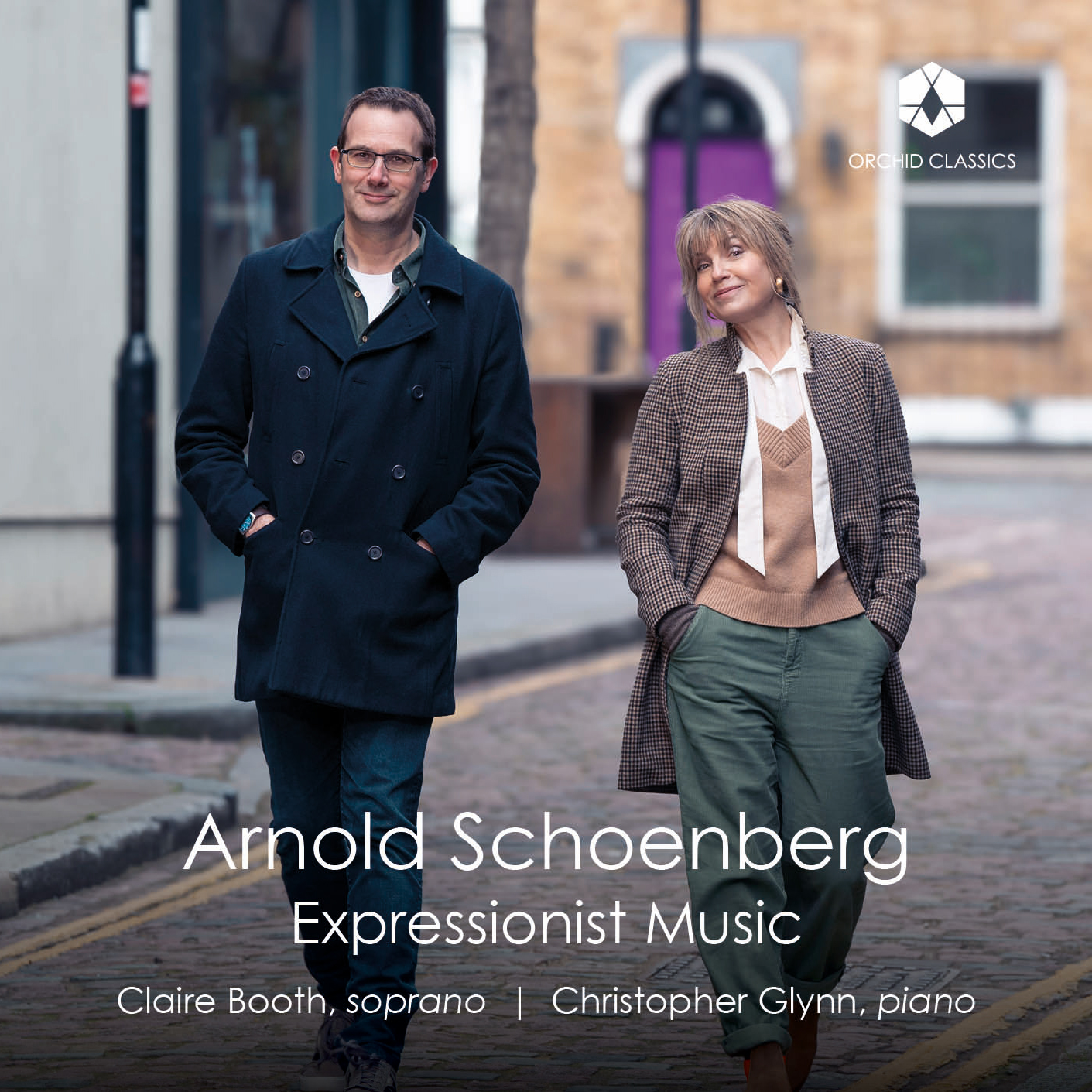

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

Expressionist Music

Claire Booth, soprano

Christopher Glynn, piano

Release Date: May 24th

ORC100306

EXPRESSIONIST MUSIC

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Expectation

1. Erwartung, Op.2 No.1

2. Alles, Op.6 No.2

3. Hochzeitslied, Op.3 No.4

Flesh

4. Mädchenlied, Op.6 No.3

5. Schenk mir deinen goldenen Kamm, Op.2 No.2

6. Lockung, Op.6 No.7

Nocturne

7. Waldsonne, Op.2 No.4

8. Sehr Langsam, Six Little Piano Pieces, Op.19 No.3

9. Traumleben, Op.6 No.1

Hatred

10. Warnung, Op.3 No.3

11. Tot, Op.48 No.2

12. Am Wegrand, Op.6 No.6

Satire

13. Der genügsame Liebhaber (Brettl-Lieder)

14. Mädchenlied, Op.48 No.3

15. Galathea (Brettl-Lieder)

Thinking

16. Gedenken, Op.post.

17. Der Wanderer, Op.6 No.6

18. Geübtes Herz, Op.3 No.5

Winter Scene

19. Sommermüd, Op.48 No.1

20. Mein Herz ist mir gemenget, German Folksongs

21. In diesen Wintertagen, Op.14 No.2

Tears

22. Jane Grey, Op.12 No.1

23. Lied Toves: Nun sag ich dir (from Gurrelieder)

24. Sehr Langsam, Six Little Piano Pieces, Op.19 No.6

Claire Booth, soprano

Christopher Glynn, piano

Expressionist Music: A Schoenberg songbook

As a song duo, we like something to chew on. And not much in the repertoire is chewier than the songs of Arnold Schoenberg. With their dark beauty, primal intensity, profound sensuality and searing honesty, they are unaccountably neglected by singers and pianists, many of whom turn readily to Strauss, Mahler and Wolf – even Zemlinsky and Korngold – but rarely open the Schoenberg volume.

Well, perhaps not unaccountably. Because the inescapable truth is that a century on, Schoenberg is still not box office. But for anyone who believes that Schoenberg is cold, cerebral and unapproachable, we can only say this: try the songs. Having explored every single one of them (as we did over a few intense days one summer), it’s impossible not to be struck by just how much magnificent music there is to discover, and that is what we have tried to celebrate in this recital.

Song was, above all, the medium in which Schoenberg found his voice. Time and again, in the first third of his career, it was poetry that fired his creativity and led him onto new musical ground. Interrelations between artforms always fascinated Schoenberg, and this was also the period in which he developed his so-called ‘second profession’ as an amateur artist, insisting that painting is ‘the same to me as making music’. It led to a deep friendship with the painter Wassily Kandinsky, and the parallels between these two artistic giants are many and fascinating. Both were interested in the translatability of one kind of artistic medium into another. Both placed truth above beauty, the inner nature of things above their outward appearance; and both were deeply concerned with the irrational, unconscious and intuitive.

In other words, they were both expressionists, exponents of the movement through which so many artists expressed anxiety and unease with the world at the beginning of the 20th century. Musing on the importance of painting for Schoenberg in those early years, we noticed how often the subjects of his songs and his pictures went hand in hand, and came up with the idea of building a

recital programme around eight of his canvases, especially those exploring emblematic themes of expressionism.

Here, then, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of his birth, is a recital of our favourite Schoenberg songs, arranged in groups to correspond loosely with some of his most striking paintings. As one critic has written, ‘Schoenberg’s music and Schoenberg’s pictures: that will knock your ears and eyes out at the same time.’ We hope listeners enjoy the fierce originality, soul-baring intensity and high emotional voltage of this music as much as we have.

Claire Booth and Christopher Glynn

Expectation

The painterly qualities of Richard Dehmel’s poem Erwartung clearly inspired Schoenberg, who finds vivid harmonies to evoke moonlight on a sea-green pond, gleaming opals, a red villa and a pale white hand beckoning. ‘Colour is so important to me, he wrote, ‘colour that is expressive in its relationships’. Expectation is also the theme of Alles, composed by Schoenberg as a 28th birthday gift for his wife Mathilde and imploring her to ‘wait for the night, until we see all the stars’. And it was surely also Mathilde that Schoenberg had in mind when he set a Danish wedding poem about the ‘brightness of hope’ in 1901, the year of their own marriage.

Flesh

Schoenberg always had an eye for the erotic. In Mädchenlied we encounter a girl triumphantly discovering her sexuality. Schenk mir deinen goldenen Kamm is a vision of Jesus longing for Mary Magdalene, but it is the tenderness, not the blasphemy, that Schoenberg seizes on, especially in an unforgettable final ‘Magdalena!’ He responds no less vividly to the predatory pursuit (or is it a playful chase?) described in Lockung, creating a sound world – not quite in any key – that is as transgressive and ambiguous as the poem.

Nocturne

Schoenberg was often drawn to the world of night. Waldsonne is full of wood-magic, evoking the ‘brown, rustling nights of the forest’ and the golden glow of dream-memories. It melts into the nocturnal sounds of the third of his Op.19 piano pieces, before we go even deeper into the world of dreams with Traumleben, one of the most rapt and ecstatic of all his songs.

Hatred

Schoenberg never shies away from difficult emotions. ‘Complex human nature requires complex music’, he once said – and we find both in Warnung, a song full of snarl and dark menace. Tot is a late song (from 1933) that shrugs at the unfairness of life and sounds like an epitaph being etched into a gravestone. It makes a stark contrast to the tumult of Am Wegrand, which depicts the indifference of society to a misfit forced to sit on the sidelines of life.

Satire

Two months after he was married, Schoenberg quit a dull bank job and moved to Berlin, taking a job as music director at the Überbrettl theatre-nightclub to make ends meet. One of the results was a set of cabaret songs in which we hear Schoenberg relishing the sly, self-satisfied innuendos of Die genügsame Liebhaber and retelling the Pygmalion myth in Galathea, about an artist over in love with his own lascivious fantasy. Twenty years later, the Nazis were shutting down Berlin’s cabaret clubs, but a vein of political satire lived on in Schoenberg’s music: the office girl in Mädchenlied is so bored of her bourgeois existence that she would consider any escape – a brothel, a monastery, or just jumping ‘into the water’.

Thinking

Gedenken is an undated and little-known early song that muses on solitude, loneliness and the passing of time. Similar themes are explored on a much grander scale by Nietzsche in his poem Die Wanderer – a sad dialogue between a wanderer and a singing bird. A simpler, happier life philosophy is expressed in Geübtes Herz, one of Schoenberg’s most beautiful love songs, in which a ‘practised heart’ is compared to a virtuoso’s much-played violin.

Winter Scene

Three songs about keeping going through the bleakest of times. Composed in 1933, just before he left Nazi Germany for America, Sommermüd reminds us to count our blessings, for ‘there are many without a star who had to die’. Mein Herz ist gemenget is a folksong lamenting the pain caused by an unfaithful lover, arranged by Schoenberg in the style of church music from two centuries earlier, as if to say: ‘have faith, this is an old story’. Hope is also the message of In diesen Wintertagen, composed during a tumultuous period in Schoenberg’s marriage, perhaps because of its promise that winter cannot touch souls who share a ‘blessed love’.

Tears

More than one critic has seen in this painting an expression of the anguish and isolation Schoenberg experienced as a result of an utterly uncompromising nature. He often saw himself as a divinely chosen martyr, so perhaps it is not surprising that one of the most searing of all his songs is the ballad Jane Grey, in which we walk beside the young queen as she goes to her execution. He identifies, too, with the tragic and doomed figure of Tove, as she declares her love for King Waldmar in a song (originally for voice and piano) that became one of the most famous moments of Gurrelieder. We end with the haunting bell-chords of a tiny piano piece Op.19, No.6) that Schoenberg composed on returning from the burial of Gustav Mahler, one his dearest friends and staunchest supporters.

Christopher Glynn

A Word about the Musicians

Performing internationally for over twenty years, Claire Booth and Christopher Glynn are established as one of today’s most innovative and imaginative song duos. In recent years, their trailblazing programming has also been captured on disc in series of acclaimed single-composer surveys on Orchid Classics. Folk Music celebrated the maverick genius of Percy Grainger and was credited with spearheading a revival of interest in a much-neglected composer. ‘It’s the sparkle they give,’ said BBC Radio 3’s Record Review, ‘it’s the care, it’s the attention to detail, the love of the music and the incredible characters that they manage to draw out of every song.’ Lyric Music was dedicated to the music of Edvard Grieg and singled out by BBC Music Magazine as ‘revelatory’, while Gramophone noted ‘Booth and Glynn are on fire here’. Their third album, Unorthodox Music traced a ‘cradle to grave’ arc through the songs and piano pieces of Modest Mussorgsky, described by the Guardian as ‘brilliantly conceived’ and by the Irish Times as ‘a vivid treasure trove of vivid storytelling’. Their latest album Expressionist Music is a deep dive into the music of Arnold Schoenberg, celebrating his 150th birthday with typically intrepid performances and inventive programming.