Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Natalia Lomeiko, violin

Dinara Klinton, piano

Clara Schumann

Robert Schumann

Karol Szymanowski

Sergei Prokofiev

Release Date: July 19th

ORC100313

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Three Romances, Op.22

1. Andante molto

2. Allegretto

3. Leidenschaftlich schnell

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

4. Fantasy in C major

Arranged by Fritz Kreisler

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Mythes, Op.30

5. La fontaine d’Arethuse (The Fountain of Arethusa)

6. Narcisse (Narcissus)

7. Dryades et Pan (Dryads and Pan)

8. Nocturne and Tarantella

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Five Pieces from Cinderella

9. Waltz

10. Gavotte

11. Passepied

12. Winter Fairy

13. Mazurka

Natalia Lomeiko, violin

Dinara Klinton, piano

The unifying idea behind the musical works in this album is that of transcendence into otherworldliness, or indeed the passage from reality to a fantasy world, starting with the composers themselves and their escape from their own personal struggles, and extending to the listener, who is thus introduced to a magical atmosphere of fairy tales, myths, and exotic soundscapes. As we will see in detail below, Clara Schumann very successfully sought self-forgetfulness in composing, which offered her an escape from an unfortunate reality where women were thought to be not suited to composition. Her husband, Robert Schumann, opted for the freedom of the fantasy form to escape the classical compositional forms he often found himself confined to, and pushed the boundaries in violin writing in this late work, the Fantasie Op.131. Karol Szymanowski chose Ancient Greek mythology to create the dreamlike atmosphere in his Mythes, while dance helped him escape the reality of his own disability and Middle Eastern aromas added to the mood in his Nocturne and Tarantella. Finally, in the midst of World War II and Prokofiev’s incredibly difficult personal circumstances at the time, it is a fairy tale and the magic attached to it that takes centre stage in his compositional work.

There is a poignancy about Clara Schumann’s music, even before actually listening to it. Her exceptional talent for composition was stifled due to the outdated yet pervasive belief that women were inherently unsuited to compose music for public consumption. However, she was in no way silenced; she may have famously stated that women were not born to compose, but she was certainly born and raised to play the piano and was for some time the more famous musician in the Schumann family. Composing gave Clara great pleasure; in her own words, ‘there is nothing that surpasses the joy of creation, if only because through it one wins hours of self-forgetfulness, when one lives in a world of sound’.

Her Three Romances were composed in 1853 and dedicated to celebrated violinist Joseph Joachim, with whom Clara took the pieces on tour. Joachim continued to perform the romances on his own tours, with the king allegedly being in ecstasy over the compositions. The three movements are exciting, contrasting, and are brimming with distinctive character. The immensely passionate first romance is built on a very emotional melodic framework, with a lyrical songlike flowing tune in the violin part, a very effective dialogue between the two instruments and a sentimental reference to Robert Schumann’s First Violin Sonata. The second romance has a nostalgic, with a pervasive sense of melancholy permeating the movement. The syncopated and lyrical main theme, which goes through several variations in its short span, is animated by trills in the violin part and complemented by energising piano figures. The third and final romance, Leidenschaftlich schnell (meaning passionate, fast), opens rhapsodically with rolling arpeggios on the piano, over which the violin soars with a charming and optimistic song. The subsequent variations maintain an engagingly lyrical quality as the violin sustains its ethereal mood, held aloft by the piano’s unrelenting and bubbling accompaniment. At the end of the work, the piece slows down and beautifully resolves with the lower end of the violin register. Schumann is very idiomatic with her violin writing, which makes this composition especially popular within violin repertoire.

Robert Schumann’s Fantasie in C major, Op.131, originally for violin and orchestra, was composed in 1853, the same year his wife Clara composed her Three Romances, after a request for more violin repertoire by Joseph Joachim, who immediately performed it in Düsseldorf, and later in Leipzig and Hannover. It was declared, after its Leipzig performance, to have been Schumann’s best concert piece. However, like many of his last works, it was thought to be marred by his declining mental health and was soon neglected. Violin virtuoso and composer Fritz Kreisler arranged the work for violin and piano in 1937, in an attempt to revive it.

The fantasie is one of the freest possible musical forms and characteristic of the Romantic period, during which many composers sought expression outside of Classical forms. Cast in one movement, the work is a rich tapestry of emotions, ranging from expressive lyricism to lively virtuosity. It begins deceptively in A minor with a sombre introduction, which soon gives way to a sprightly theme in C major, which becomes a recurring refrain throughout the rest of the work and also forms the basis of the coda.

Szymanowski’s Mythes mark the start of the composer’s second compositional period, his first period having been an obvious display of his great affinity for late romantic German masters such as Brahms, Strauss and Wagner. Szymanowski’s new compositional style was a direct outcome of his world travels in 1914, when he visited Sicily and North Africa, expanding his imagination and interest in exotic culture and mythology, and then went on to spend time in Paris, where he was introduced to Ravel, Debussy, Cocteau and Stravinsky. A year later, Mythes was born and with it came a new musical language, greatly affected by French impressionist music, as well as the many conflicting concepts of the fin de siècle.

Each of the three Mythes is based on an ancient Greek myth; the first two, in line with impressionist music ideals, focus on the atmosphere created by the inspiring beauty of the myth, rather than the story itself. In La fontaine d’Arethuse, where the nymph Arethusa is turned into a stream while fleeing from river god Alpheus, Szymanowski expresses the mood that is created by the presence of flowing water. In Narcissus, where a hunter who was known for his beauty falls in love with a reflection in a water pool not realising it was his own and becomes entranced by it, the still and clear water surface in which Narcissus’ beauty is reflected leads the central atmosphere of the movement. In the third myth, Dryades et Pan, the musical content takes on a more anecdotic sense, in Szymanowksi’s own words, as we perceive the murmuring of the forest on a hot summer night, thousands of mysterious voices overlapping in the darkness, the fun and dancing of the Dryads – the tree nymphs and guardians of the forest, followed by the dreamy sound of a pipe and the appearance of Pan, god of nature, his subsequent departure and the return of the Dryads’ dance, before everything calms down in the silence and freshness of dawn. The mood of these three fantasy worlds is fulfilled with a highly sophisticated harmony and a wealth of violin techniques, including trills, glissandi combined with tremolo, harmonics and notably in the most instrumentally innovative third myth, the presence of quarter-tones. These are combined with a light and delicate texture to create still yet internally shimmering and vibrant soundscapes.

Nocturne and tarantella was composed in the same year as Mythes and starts off in common musical territory, with long elegant lines soaring high above the piano accompaniment in Nocturne, before intermittent outbursts of Spanish dance are introduced, alternating this first part’s atmosphere between a slow and dreamy exoticism, and energetic and at times agitated Mediterranean folklore. It has been argued that Szymanowski’s fascination with dance and its rather frequent appearance in his second period works was owing to his knee disability, his compositions perhaps serving as an escape from his own reality of being unable to dance. The Tarantella was allegedly composed in a single evening, while drinking with violinist Paweł Kochański, who performed the premiere of the piece, and August Iwański, to whom the work is dedicated. In a rapid 6/8 rhythm and comprising an array of technical features for the violin, the Tarantella is rich in impressionistic harmony but also infused with Middle Eastern aromas.

Prokofiev’s Five Pieces from Cinderella are taken from the first two acts of his ballet, composed to complement Nikolai Volkov’s libretto. The ballet score, one of his most melodious and celebrated compositions, was commissioned following the success of his ballet Romeo and Juliet and Prokofiev started working on it in 1941, but did not complete it until 1944, due to World War II and his work on the opera War and Peace. Prokofiev’s lushly passionate, romantic and virtuosic score captures perfectly the drama and atmosphere of the famous fairy tale, with its added element of magic.

The first piece is the very colourful Waltz, from Act II, which evokes the imagery of a royal ball, with its swirling gowns, dazzling ballroom and with hints of the ticking clock, representing Cinderella’s impending deadline. Next, we hear the Gavotte from Act I, a traditional French dance characterised by its moderate tempo and graceful steps, infused by Prokofiev with his signature blend of lyricism and wit. The Passepied, a lively and graceful dance, also of French origin, is filled with charm, lightness and intricate rhythms. The fourth piece, the delicate and shimmering Winter Fairy from Act I, is a solo variation of the winter fairy, at the end of which she hands Cinderella her sparkling new cloak to wear to the ball. Finally, we hear the Mazurka from Act II, a traditional Polish dance in triple meter that adds folkloric charm to the story, with its lively, syncopated rhythms propelling the dance forward. The five pieces are ingeniously rewritten by Prokofiev for violin and piano to retain the magic and drama created by the large orchestra of the original score.

Markella Vandoros, February 2024

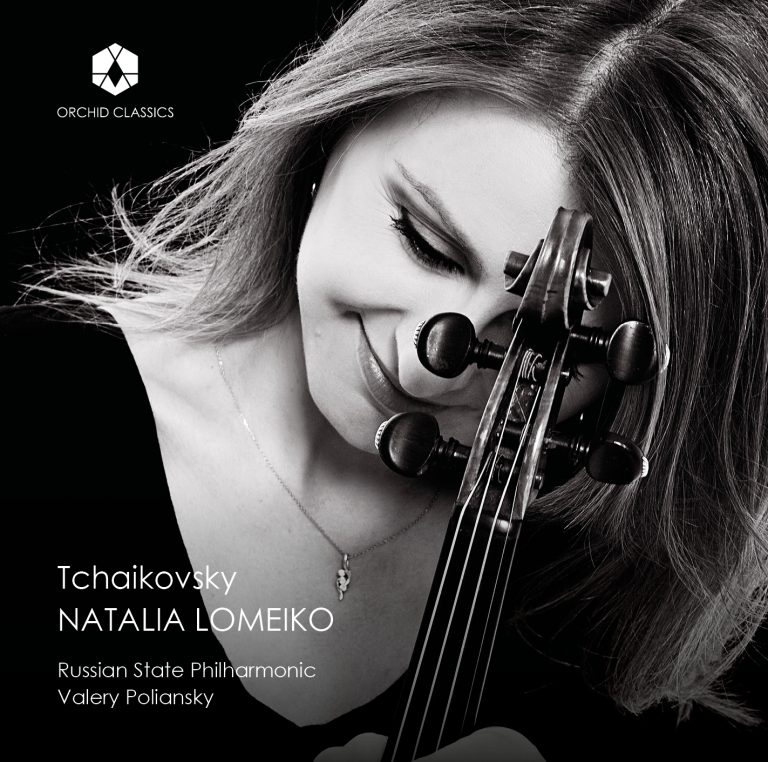

Natalia Lomeiko

Violin

Born into a family of musicians in Novosibirsk, and settling in New Zealand in 1996, Natalia has established herself internationally as a versatile performing artist.

Since her debut with the Novosibirsk Philharmonic Orchestra at the age of seven, Natalia has performed as a soloist with many orchestras, such as the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Lord Menuhin, Philharmonia, Singapore Symphony, New Zealand Symphony, Auckland Philharmonia, Christchurch Symphony, Tokyo Royal Philharmonic and numerous others.

Natalia has collaborated with several distinguished conductors including Lionel Bringuier, Matthias Bamert, Arvo Volmer, Olari Elts, Vladimir Verbitsky, Miguel Harth-Bedoya, Eckehard Stier, Mikhail Gerts, Valery Polyansky, Yuri Simonov, Pavel Kogan and Nabil Shehata.

Following her wins at ‘Premio Paganini’ and Michael Hill International Violin Competitions, Natalia recorded with pianist Olga Sitkovetsky for Dynamic, Fone, Trust Records, Atoll, and with violinist/violist Yuri Zhislin for Naxos and pianists Ivan Martin and Dinara Klinton for Orchid Classics. She has also recorded for SOMM with Alexander Karpeev.

Natalia has performed extensively as a soloist and chamber musician in prestigious venues including Carnegie Hall, Wigmore Hall, the Kings Place, the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Buckingham Palace, the Barbican and the Royal Festival Hall. She has performed chamber music with such distinguished musicians as Maxim Vengerov, Gidon Kremer, Yuri Bashmet, Ivan Martin, Tabea Zimmerman, Claudio Bohorquez and Daishin Kashimoto.

Natalia has been appointed a Professor of Violin at the Royal College of Music in London in 2010 and currently resides in London.

Dinara Klinton

Piano

After sharing the top prize at the 2006 Busoni Piano Competition age 18, Dinara took up a busy international concert schedule, appearing at many festivals including the “Progetto Martha Argerich” in Lugano, the Cheltenham Music Festival, the Aldeburgh Proms and “La Roque d’Antheron”. She has performed at many of the world’s major concert venues, including the Royal Albert Hall, Royal Festival Hall, Barbican Centre and Wigmore Hall in London, Berliner Philharmonie and Konzerthaus, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, Gewandhaus Leipzig, New York 92Y, Cleveland Severance Hall, Tokyo Sumida Triphony Hall, Great Hall of Moscow Conservatory and Tchaikovsky Concert Hall.

Her concerto engagements include The Philharmonia, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Lucerne Symphony Orchestra and others. Dinara combines her performing career with piano professor positions at the Royal College of Music and the Yehudi Menuhin School.

As a solo recording artist, she has received widespread critical acclaim. Her album of Liszt’s Études d’exécution transcendante, released by the German label GENUIN classics was selected by BBC Music Magazine as Recording of the Month. Dinara’s debut album ‘Music of Chopin and Liszt’ was made at the age of 16 with the American label DELOS. Her other albums include a CD of Chopin’s music by The Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Poland and the complete Prokofiev Piano Sonatas released by Piano Classics, as well as a rarely played Balakirev’s Piano Concerto No.1 with Niederrheinische Sinfoniker, released by Dabringhaus und Grimm.

Dinara’s music education started in the age of five in her native Kharkiv, Ukraine. She graduated with highest honours from the Moscow Central Music School under Valery Piassetski, and the Moscow State Conservatory P.I. Tchaikovsky under Eliso Virsaladze. She went on to complete her Master’s degree at the

Royal College of Music under Dina Parakhina. Dinara also attended masterclasses at the Lake Como Piano Academy and worked with Boris Petrushansky in the Imola Piano Academy.