Artist Led, Creatively Driven

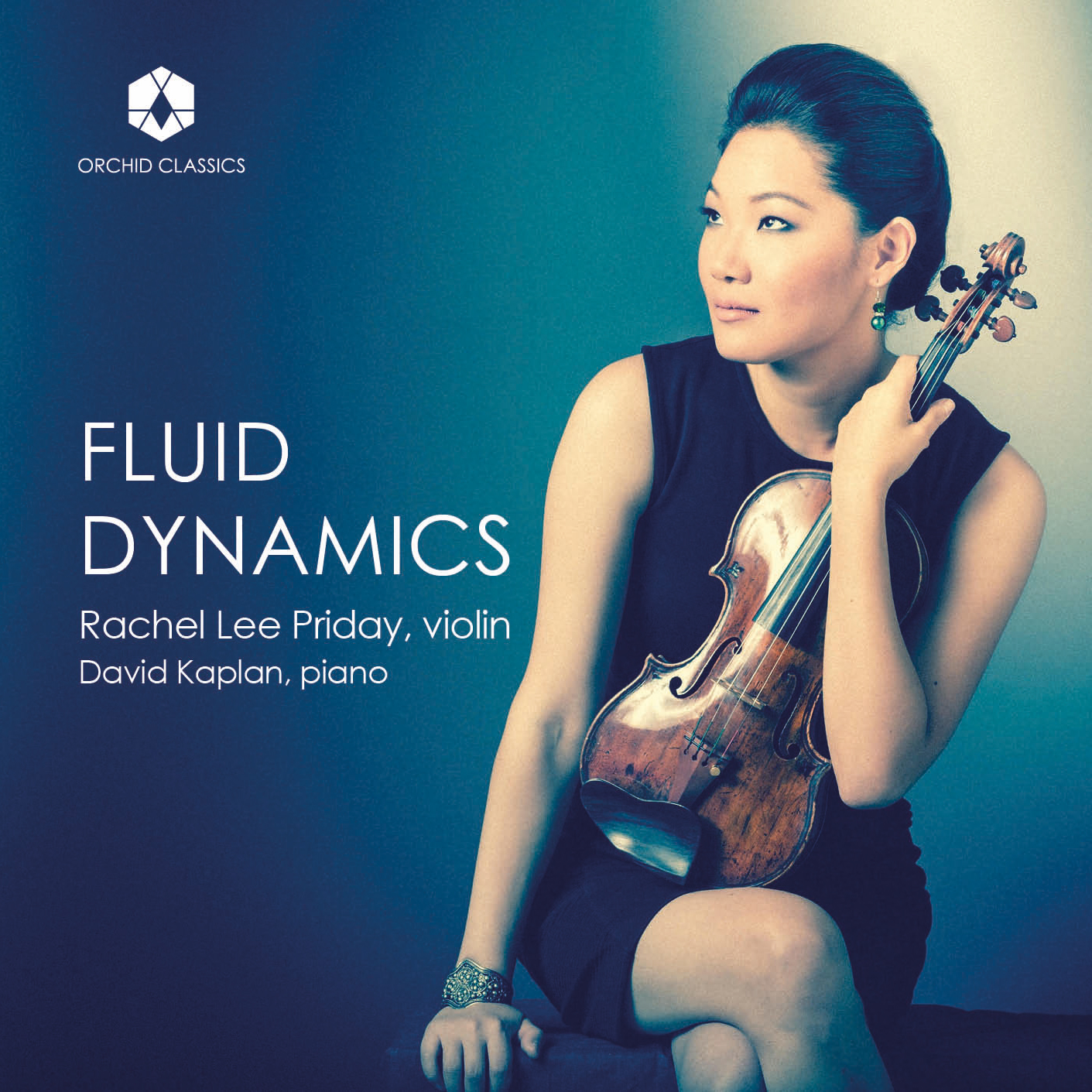

FLUID DYNAMICS

Rachel Lee Priday, violin

David Kaplan, piano

Release Date: Aug 23rd

ORC100323

FLUID DYNAMICS

Gabriella Smith (b.1991)

1. Entangled on a Rotating Planet

Paul Wiancko (b.1983)

2. Waterworks

Cristina Spinei (b.1984)

3. Convection Loops

Timo Andres (b.1985)

4. Three Suns

Leilehua Lanzilotti (b.1983)

5. ko’u inoa

to speak in a forgotten language

6. I

7. II

8. III

Christopher Cerrone (b.1984)

Sonata for Violin and Piano

9. I Fast and focused, with gradually increasing intensity

10. II Still and spacious, but always moving forward

11. III Dramatic, violent, rhythmic, very precise

Rachel Lee Priday, violin

David Kaplan, piano

‘Loving these…’ , ‘so so cool…’, ‘a beautiful metaphor… ’, ‘a choreography of colours…’ No, these are not quotations from glowing reviews of Rachel Lee Priday’s playing, but the next best thing: they are the reactions of her composer-collaborators on being asked to take part in this project, an intriguing and musically rich partnership between Rachel, six composers… and an oceanographer.

In the autumn of 2019, Rachel joined the School of Music at the University of Washington and was asked to attend an orientation day with other new faculty. ‘Georgy was literally the first person I saw when I opened the door,’ she recalls. ‘And of course we talked about what we were just hired to do. A couple of weeks later we got a coffee on campus and walked to his fancy Ocean Sciences building. He told me then that he studies chaos, which I thought sounded pretty intriguing!’

Georgy Manucharyan was a new faculty member of Washington’s School of Oceanography, where he researches what he describes as ‘the physics of the ocean – how currents move, and what causes their motion. The science I do is really complicated, but we try to demonstrate the underlying concepts using fluid dynamics experiments in the lab.’ And that, curiously enough, is how this project began. Georgy spent the next year producing videos of these experiments and began experimenting with using classical music to ‘amplify’, as he puts it, the message of the movements visible on-screen. He was hoping to put the finished projects up online: ‘kids could get inspired to do music, or fluid dynamics, or oceanography… or just become aware of environmental and climate change issues.’

But there was a limit to what Georgy felt able to do alone. ‘I can’t play! I’m not a musician,’ he admits regretfully. So he sent some of his early attempts to Rachel to get her feedback on his music-video pairings, and asked her to suggest other pieces that suit these filmed experiments. ‘In talking to him more,’ Rachel explains, ‘I found it interesting that every time he does the same experiment it comes out differently: even though the principles are the same, you just never know what’s going to happen. And I related that to what a performer does – to performance and interpretation, chance and timing, how every time we play it’s different.’ Rachel moved from suggesting pre-existing pieces to contacting composers in order to commission new work. There was, importantly, no fixed brief: just the chance to view some of the videos, decide what might work, and how the music and film footage might interact. And gradually, as more and more composers eagerly took up the challenge, a larger project – of this album, and of live musical performances with visuals – was born.

The first newly completed work was by composer and ecologist Gabriella Smith. As luck would have it, she too had just moved to Seattle and visited Georgy’s lab to see some of his experiments in person. Her Entangled on a Rotating Planet uses a geostrophic adjustment experiment, simulating the interplay of wind and water at a surface level. The score is measured roughly in time rather than bar lines, so there is built-in room for manoeuvre; and the player is asked to make ‘fluttering, shimmering’ or ‘messy’ pitch gestures that either merge seamlessly into something new or are cut off and sent reeling in a new direction. By contrast Cristina Spinei, who is highly regarded for her work with a range of distinguished American dance companies, wanted a tight brief and pre-cut video to ‘choreograph’ musically. ‘She wrote it to the second for that video,’ Rachel tells me. And it shows: Convection Loops takes the name of its experiment at face value, Spinei deploying a loop pedal to gradually stack layer upon layer of solo violin lines as the colour inks drop, swirl, and are pulled through the water. It is a beautiful, mesmeric work that casts each colour as a kind of dancer in its own right.

It’s striking that a number of the composers writing for this project are themselves string players: Smith is a violinist, Paul Wiancko is a cellist (Wiancko plays with the Kronos Quartet), whilst Leilehua Lanzilotti is a violist. Lanzilotti’s ko’u inoa was composed in 2017 as a concert work – ‘a homesick bariolage based on the anthem Hawai’i Aloha’ which she first composed as a way to feel connected to her home country of Hawaii whilst spending time in Germany. The title translates to ‘my name is’, and its minimally notated, free-flowing score asks for the violinist to seek out the overtones and variety of colours available by moving their bow from the normal playing position across the strings, up towards the fingerboard and back down towards the bridge of the instrument. The player is also asked to hum a succession of consonants and vowels through the closing section as they play. The piece pairs beautifully with the wave experiment that brings attention to a major problem of ocean pollution. Rachel then commissioned to speak in a forgotten language for her project with Georgy. Lanzilotti (who insisted on reading as much of Georgy’s research as possible in preparation) was watching a video of a convection experiment, and ‘was inspired by a moment when a woman’s face seemed to emerge to her’ through the twirling currents of the water. The title is taken from the poem Witness by W.S. Merwin (1927-2019), an American writer and environmental activist, and once again uses sparse notation and extended unusual techniques to explore overtones, over-pressured bowing, white noise, and whispers. This level of indeterminacy in the score allows for the performance time to vary by several minutes – this is not, in other words, an attempt to match the film second-by-second, but rather allows for freedom in the way the two interlock, presenting further opportunities for expanding and reshaping the work in a pure concert rendition.

Paul Wiancko’s Waterworks turns the entire film-to-music process on its head. Inspired by the violence and energy of a whirling red vortex, it spins along in ‘joyfully mechanical’ circling figuration, often in double stops, sometimes in sudden and unexpected new directions. Wiancko composed his piece as a freestanding entity and the video was then cut to fit. ‘Something about the rapid changes/alterations/additions to the constant energy of the vortex speaks to my music well,’ he observes. ‘And the red dye brings in some interesting notes of drama/science/violence.’

The remaining works on this disc Rachel describes as ‘old friends of mine’. She commissioned Timo Andres’ Three Suns in 2018 and they gave its filmed premiere during the Coronavirus pandemic. The suns of the title refer to repeated figurations which, as they rise, ‘gradually take on varied characters, threatening to pull apart the structure.’ The whole is framed by a slow-moving, chordal chorale, the calm before and after the storm – whilst the faster music is matched on screen with the luminous beauty of rainbow-refracting surface tension patterns on bubbles. Finally, Christopher Cerrone’s Violin Sonata was written for Rachel in 2015. (Cerrone wryly recalls in his notes for the piece that he remembers telling his college composition teacher, ‘I swear I will never write a piece for violin and piano’.) It has the same sense of high energy and colour at its opening as several of the other works on this disc, but this time the performance instruction comes at around 35 bars in to ‘sneak in piano gradually’, the volume and intensity of the two players’ lines eventually building to what Cerrone describes as ‘a roaring and vibrant chorale’. The pianist leads us directly into the second movement, the violin joining with a series of ever-varying articulations and effects on each bow stroke. Rachel was struck by how appropriate to the project this movement, in particular, seemed to be: ‘the piano and violin get out of sync progressively and then at a certain moment it snaps back in time’ – a perfect match for a video showing light illuminating complex interference patterns of two-dimensional turbulence on the surface of a soap bubble. A furiously fast finale, all stabbing attack and ringing chords, eventually gentles and the sun bursts through for the final few pages, the chorale harmonies of the first movement returning.

Was this impressive array of different inspirations, figurations, moods, styles and working methods what Georgy Manucharyan expected when he and Rachel began to collaborate? ‘It was completely new! Full of suspense and very sharp transitions.’ He sings a little passage and giggles. ‘Fluid dynamics is sort of smooth, right? And most of the music I’ve listened to is Romantic music. This new music has a thousand chords played in a few seconds and I was like woah, what is this?!’ (Rachel was clearly sympathetic to this view: ‘All these pieces are pretty physical when you’re playing them!,’ she says.) As he got used to these new soundworlds, Georgy realised that the composers had often picked up on different aspects or levels of motion in the experiments than those he had been focussing on from a scientific perspective. ‘Then I understood what the composer was seeing in the video.’ It’s been a learning process for all, clearly. ‘And an exceptionally fulfilling experience,’ Georgy agrees. The live show will follow shortly, in versions tailored for every space from fully-equipped theatres to museums and other venues. ‘Maybe even aquariums!’, Rachel beams. This is a fascinating on-going experiment – compositional, performative, and scientific – with many more exciting tests still to run.

© Katy Hamilton

Rachel Lee Priday

Violin

Known for spectacular technique, sumptuous sound, and deeply probing musicianship, alongside “irresistible panache” (Chicago Tribune), violinist Rachel Lee Priday is passionately committed to new music and creating enriching community and global connections through wide-ranging repertoire and multidisciplinary collaborations that reflect a deep fascination with literary and cultural narratives.

Priday has appeared as soloist with major international orchestras including the Chicago, Saint Louis, Houston, Seattle, and National Symphony Orchestras, the Boston Pops, and the Berlin Staatskapelle. Her distinguished recital appearances have brought her to eminent venues such as Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival, Chicago’s Ravinia Festival and Dame Myra Hess Memorial Series, Paris’s Musée du Louvre, Germany’s Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival and Switzerland’s Verbier Festival. She has premiered and commissioned works by composers including Matthew Aucoin, Christopher Cerrone, Gabriella Smith, Timo Andres, Leilehua Lanzilotti, Cristina Spinei, Melia Watras, Paul Wiancko and many more.

Priday began her violin studies at the age of four in Chicago, after she saw the puppet Lamb Chop pretend to play the violin, and shortly after moved to New York City to study with iconic pedagogues Dorothy DeLay and Itzhak Perlman at The Juilliard School. She holds degrees from Harvard and the New England Conservatory, and has served on the faculty of the University of Washington since 2019. She performs on a Giuseppe Guarneri violin (“filius Andreae”).

David Kaplan

Piano

David Kaplan is a New York-born piano soloist and chamber musician, praised by the Boston Globe for “grace and fire” at the keyboard. He has appeared as soloist with the Britten Sinfonia and Das Sinfonie Orchester Berlin, and in the 2023-24 season makes debuts with the Symphony Orchestras of Hawaii and San Antonio. He has given recitals at the Ravinia Festival, Washington’s National Gallery, and New York’s Carnegie and Merkin Halls, and in addition to his work with Decoda, has collaborated with the Attacca, Ariel, and Tesla String Quartets. Kaplan is the Assistant Professor and Inaugural Shapiro Family Chair in Piano Performance at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, where he has taught since 2016. A graduate of UCLA, Yale, and a Fulbright scholar in Berlin, Kaplan’s teachers and mentors include Claude Frank, Walter Ponce, Miyoko Lotto, and Richard Goode. Away from the keyboard, he loves cartooning and cooking, and is mildly obsessed with classic cars.