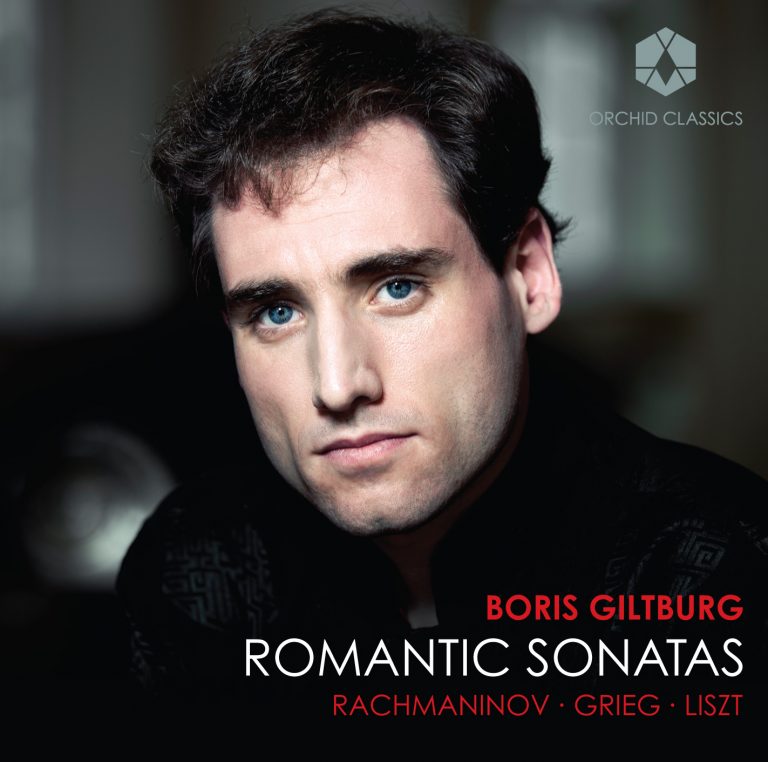

Artist Led, Creatively Driven

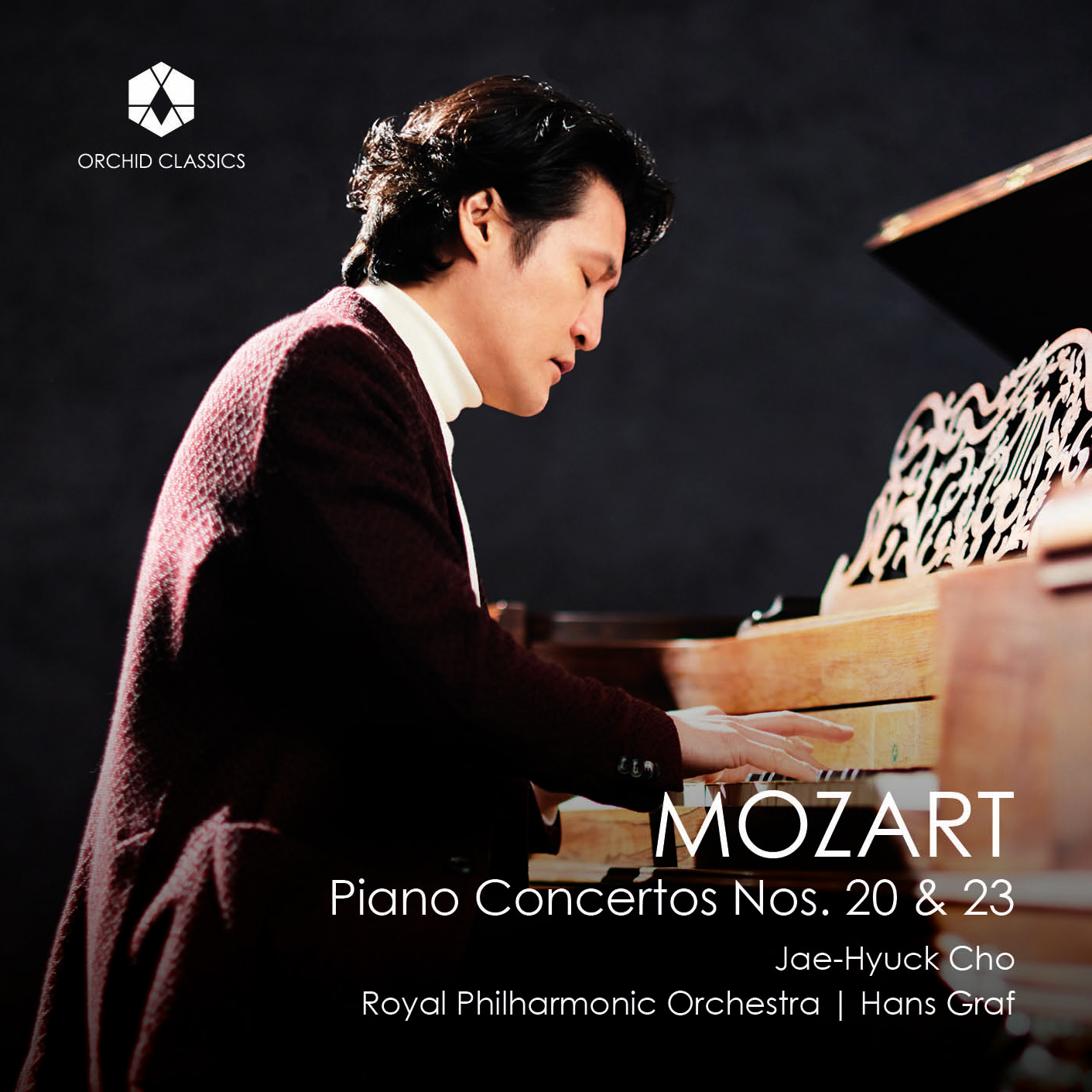

MOZART

Jae-Hyuck Cho, piano

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Hans Graf, conductor

Release Date: Sept 20th

ORC100329

MOZART CONCERTOS

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No.20 in D minor, K.466

1. I Allegro (Cadenza by J. N. Hummel)

2. II Romance

3. III Allegro assai (Cadenza by R. Casadesus)

Piano Concerto No.23 in A major, K.488

4. I Allegro

5. II Adagio

6. III Allegro assai

Jae-Hyuck Cho, piano

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Hans Graf, conductor

This album was recorded in August 2020, during a brief window of time when we all thought the situation was changing for the better since the initial appearance of the COVID-19 virus in late 2019. However, we still had to observe strict measures such as restrictions and social distancing, so it took an elaborate and complex logistic dance to make it happen. Recording sessions are challenging for many reasons. However, for this album, they were even more difficult due to social distancing. Along with wearing face masks, the orchestra members were spread out wide, with an almost oxymoronic and intolerable amount of space between each member. Players who could not wear masks, such as wind instruments, were placed even farther away and apart from one another, and this unusual setting resulted in various minute but undoubtedly noticeable and confusing delays; it took all of us a while to adjust to this new situation.

As performing artists, we are trained to adapt to the differing acoustic properties of a given performing space. With such a strange setting, this project instilled in us new and different ways to cope with yet another unique condition. It was a volatile and unpredictable time with ever-changing status and conditions in the world. So many things could have happened to cause this project to be cancelled. However, we made it to the end thanks to the cooperation and determination of everyone who was involved. I offer my deepest gratitude to every single individual who was involved in this project. I would like to give special thanks to my dear friend Hans Graf, who was at the frontline of it all; to the entire staff and members of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra for their exceptional and creative efforts to keep the project alive; to the producer Anna Barry and the engineers, GP Music’s Jonas Grunau, Paul Bates, and last but not least, to Ulrich Gerhardt who not only prepared for me a beautiful instrument but also being there as a friend in trying times.

When Richard Wagner was coining the word Gesamtkunstwerk, which roughly translates as a ‘complete work of art,’ I don’t think it occurred to him then that when referring to the various art forms by different artists that are to be combined to create a new and singular artistic work, it would even include the artful ways of figuring out how to get people together during a pandemic when the world was under severe restrictions on traveling and gathering. It was cathartic to “rebel” against the virus, and I think Herr Mozart would’ve also liked it if he heard about this.

Jae-Hyuck Cho, April 2024

Over the course of the 1780s, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed sixteen piano concertos. He had settled permanently in Vienna in 1781, and rapidly sought to establish himself not only as a brilliant composer, but also as a keyboard virtuoso – which meant writing pieces to demonstrate his skill. To this end, Mozart’s piano concertos act as a kind of bellwether of his success: the more he wrote in a given year (and the writing was almost always done with a specific and imminent performance opportunity in mind), the greater his popularity. The two concertos on this disc were composed in 1785 and 1786, during his most successful period of the decade.

The Concerto in D minor K.466 is one of Mozart’s very few piano concertos in a minor key. It’s also unusual in the manner of its interactions between the soloist and the orchestra: in many of his concertos, the two are set up as being more or less in conversation, alternating and echoing in amicable partnership. But here, we are left with the distinct impression of the piano being in opposition to the orchestra, and the result is a piece of extreme tension and high drama. And D minor was to be the key of two of Mozart’s most important later works, the opera Don Giovanni and his Requiem Mass, left incomplete as his death in 1791.

The strings pulse with anxiety as the piece begins, the hushed opening eventually giving way to outbursts from flute, oboes, horns, bassoons, a pair of trumpets and timpani – indeed the orchestra introduction showcases all the wind and brass instruments in turn. When the piano finally appears, it does not adopt earlier themes but introduces one of its own, alone, before passing the baton back to the ensemble. When we move towards a second, more optimistic musical idea, it is the soloist who offers new material that is then picked up by the wind section in light, delicate textures. We even hear the orchestra’s opening idea reconfigured in the major, as if the prevailing mood may be completely overturned. But this doesn’t stick, and we are thrown back into the minor-key torrent as the rest of the movement unfolds.

A moment of relief from this bleak world is provided by the elegant Romance, our soloist introducing the lilting melody in two parts which are then passed graciously to the orchestra. But even this has a stormy central section, the pianist’s hands leaping across each other as he throws fragments of melody between the bass and high treble of the keyboard. After the brief balm of a return to the gracious first theme with which this movement ends, the piano throws us into the Concerto’s closing Rondo. We are whipped back to D minor in a vigorous movement that is driven forward with even more propulsive energy than the first. No wonder that this extraordinary demonstration of Sturm und Drang was a favourite of Ludwig van Beethoven, who played the work in public several times and wrote his own cadenzas for the purpose.

The D minor Concerto was premiered in one of Mozart’s subscription concerts of February 1785, and his father Leopold was in attendance. He reported the event at length in a letter to Wolfgang’s sister Nannerl, reporting that the ‘admirable new piano concerto’ was so newly composed that the copyist was still writing out the performance parts when he arrived for the rehearsal! ‘Your brother didn’t even have time to play through the rondo as he had to oversee the copying.’ The piece was performed by Mozart’s pupil Heinrich Marchand in Salzburg the year after its premiere: Haydn’s brother Michael (also a highly-esteemed composer) turned the pages for Marchand, and the finale had to be played through three times in rehearsal to help the orchestra find its way through it. Presumably the many exposed passages for the wind players, as well as the rhythmic complexity of the string writing, was rather more of a challenge than their usual fayre.

Leopold Mozart’s report that the D minor Concerto was barely ready to go in time for its premiere points to the extraordinary time constraints under which his son’s concerts were organised – almost unthinkable in the twenty-first century, when artist schedules are pinned down months or years in advance. It seems that Wolfgang sometimes sketched out the opening ideas for new works in advance but didn’t complete them in full until the opportunity for a performance arose. The Concerto in A major K.488 is an example of just this practice, with the opening sketched in 1784 but the whole not finished until 1786, in time for a concert performance. Interestingly, in the years between starting and finishing the work, Mozart also changed his mind about the work’s scoring: he switched out his original pair of oboes for rather more cutting-edge clarinets. There are no trumpets or timpani in this piece, and it is altogether a far more lyrical and easy-going work than the D minor Concerto.

The Allegro foregrounds the winds in its opening melodies, setting up a gentle and almost pastoral mood – there are one or two brief turns into minor keys, but the music is quickly set back onto the straight and narrow. The pianist immediately adopts and embellishes the orchestral themes on joining the ensemble, and although this is a rather different kind of interaction from the D minor Concerto, in both cases Mozart makes all participants in the music equally responsible for introducing and developing themes, rather than simply allowing the virtuoso soloist to steal all the musical thunder.

Surely the most remarkable movement of this Concerto is its second, an Adagio in the unusual key of F sharp minor. There is tender beauty in this slow movement, but it comes with an almost unbearable sense of tragic melancholy – and the vast leaps in the pianist’s right-hand melody, as if the theme is somehow operating across three different levels of the musical atmosphere, was a device extensively exploited by Fryderyk Chopin in later decades. The generous finale is warm and joyful, its few unexpectedly dark moments quickly dispelled in a whirl of energy and delight.

© Katy Hamilton

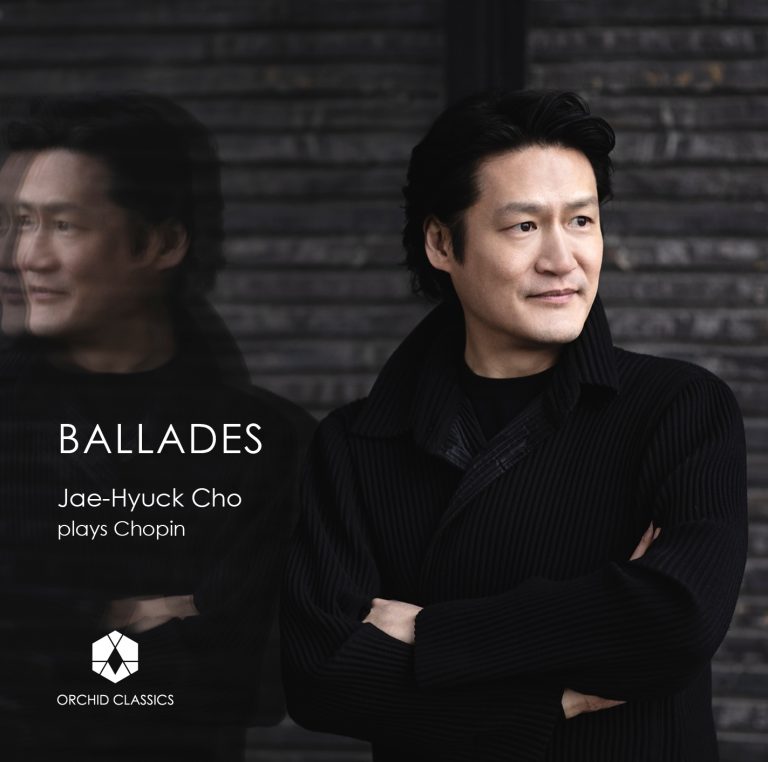

Jae-Hyuck Cho

Piano

Acclaimed pianist/organist Jae-Hyuck Cho is one of the most active concert artists in South Korea. In addition to being a soloist in recitals or as a star at the side of large orchestras, he is also considered an essential musical mediator by initiating new concert formats and series and making regular appearances on various broadcasting formats. He has been described as “a musician who is nearing perfection with an extraordinary breadth of expression, flawless technique, composition, sensitivity, intelligence, insightful and detailed playing without exaggeration.”

Jae-Hyuck Cho began studying piano at the age of five. Cho soon moved to New York, where he continued his education at the Manhattan School of Music and eventually graduated from the Juilliard School. At the same time, he began studying the organ. Today Cho is one of the few musicians who have mastered both the piano and the organ equally and chosen them as their primary instruments.

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’s (RPO) mission to enrich lives through orchestral experiences that are uncompromising in their excellence and inclusive in their appeal, places it at the forefront of music-making in the UK and internationally. Performing around 200 concerts a year and with a live and online audience of more than 60 million people, the Orchestra is proud to embrace a broad repertoire and reach a diverse audience. The RPO is unafraid to push boundaries and is at home recording video game, film and television soundtracks, working with pop stars, and touring the world performing great symphonic repertoire.

Throughout its history, the RPO has collaborated with inspirational artists and in August 2021, the Orchestra was thrilled to welcome Vasily Petrenko as its new Music Director. A landmark appointment in the RPO’s history, Vasily’s opening two seasons with the RPO have been lauded by audiences and critics alike.

As well as a busy schedule of international concerts, the Orchestra performs regularly at London’s Royal Albert Hall (where it is Associate Orchestra), the Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall and Cadogan Hall, where it is celebrating its 20th Season as Resident Orchestra. The RPO tours extensively around the UK and through collaboration with creative partners, fosters deeper engagement with communities to ensure that live orchestral music is accessible to as inclusive and diverse an audience as possible. To help achieve this goal, the Orchestra launched RPO Resound in 1993, which has grown to become the most innovative and respected orchestral community and education programme in the UK and internationally.

Hans Graf

Conductor

Hans Graf, a highly respected Austrian conductor known for his diverse repertoire and innovative programming, currently serves as Music Director of the Singapore Symphony Orchestra. Previously, Graf has held significant positions with the Houston Symphony Orchestra, the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, L’Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine, the Basque National Orchestra and the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg.

Graf has conducted most of the major orchestras across the United States, Canada, Europe, Russia, and Asia, including appearances at prestigious festivals worldwide. He has also led numerous opera productions, receiving awards for his recordings (ECHO Classic, Grammy for Alban Berg’s Wozzeck)). Graf’s extensive discography includes acclaimed recordings of Mozart, Schubert, Dutilleux, and Zemlinsky. With the Singapore Symphony Orchestra he recently recorded all the works of Mozart for Violin and Orchestra (Chloe Chua) and the rediscovered Requiem by the Polish composer Josef Kozlowski.

Born in Upper Austria, Graf studied conducting with renowned mentors and is a Professor Emeritus for Orchestral Conducting at the Universität Mozarteum in Salzburg. He has received honors from the French government and the Republic of Austria for his contributions to music.