Artist Led, Creatively Driven

PAGANINI 24 CAPRICES

Ilya Gringolts

Release Date: November 2013

ORC100039

NICCOLÒ PAGANINI (1782 – 1840)

24 Caprices for solo violin, Op.1

No.1 in E major: Andante

No.2 in B minor: Moderato

No.3 in E minor: Sostenuto – Presto – Sostenuto

No.4 in C minor: Maestoso

No.5 in A minor

No.6 in G minor: Lento

No.7 in A minor: Posato

No.8 in E flat major: Maestoso

No.9 in E major: Allegretto

No.10 in G minor: Vivace

No.11 in C major: Andante – Presto – Andante

No.12 in A flat major: Allegro

No.13 in B flat major: Allegro

No.14 in E flat major: Moderato

No.15 in E minor: Posato

No.16 in G minor: Presto

No.17 in E flat major: Sostenuto – Andante

No.18 in C major: Corrente – Allegro

No.19 in E flat major: Lento – Allegro assai

No.20 in D major: Allegretto

No.21 in A major: Amoroso – Presto

No.22 in F major: Marcato

No.23 in E flat major: Posato

No.24 in A minor: Tema con Variazioni (Quasi Presto)

Ilya Gringolts, violin

You were only sixteen years old when you won the International Violin Competition ‘Premio Paganini’, during which you were awarded two additional prizes – one as the youngest ever competitor to win, and another for the best interpretation of the Caprices. Fifteen years on, has your approach towards his famous set of etudes changed?

I suppose my approach has changed with me! It’s important to realise that my tackling this cycle has not been linear – I’ve been playing them since age eleven (number 13 was the lucky first), but rather without an overview. It’s only relatively recently that I have begun to see the curve of the cycle: the chromatic complexity, the permeating German Romanticism in these works, an almost complete lack of ‘Italianità’ (there are exceptions, but No.23 is almost a gimmick!), the tonal structure (fivefold E flat major is NOT a coincidence!) – all of the things that could not have been evident to me at the tender age of 16. I was no Einstein!

I suppose the brilliant work of my then-teacher Tatiana Liberova and my Pavlovian reflexes were responsible for the prize in 1999 – it is, however, evident, that with age more homework was needed. A good score was the beginning – it is mind-boggling to think how few people resort to the Urtext edition of the cycle, although it’s been part of our lives for some 20 years. I suppose the patronising attitude to Paganini begins there – whereas using Bärenreiter or Henle for Schubert and Mozart is now a must, Paganini is still often played from suspicious material. It’s no less mind-boggling to see how many factual misprints have been copied by various editions and set in stone by multiple recordings. It almost became for me a work of archaeology, scraping all of the soot off these wonderful pieces. It’s worth noting that most editions conveniently cover up the tricky parts making them somewhat more playable (No.5 is a case in point – the original bowing has been known for ages, yet only a handful of violinists opt for it!)

The fun really begins when one distances oneself from the technical hurdles and looks at these pieces not from the bel canto point of view – bel canto they are not and that makes them stand apart from the rest of Paganini’s output – but rather from a Schumann-Mendelssohn-Liszt inspired German Romantic paradigm. It is exactly those influences, so strongly based on harmonic and chromatic motion, that make these works so alive and vibrant, so truly romantic.

Tell us about your very first meeting with these pieces, can you remember your reaction when you saw the score for the very first time? Did you discover it yourself, or did someone entice you?

The cycle has occupied me (not without breaks) since a very early age. There was of course the curriculum – No.15 had been learned for an examination and had not been touched for 13 years afterwards – but also the business of encores. Some of these pieces work beautifully on their own, whereas others really only reveal their secrets as part of the greater whole. There were the “black sheep” that either escaped my attention (Nos.2, 12, 19) or downright terrified me (practically all that have extended staccato passages). There were Caprices that I have been polishing for years before trusting myself to take them on stage (Nos.3, 4) and the ones that I freshly picked up in the run-up to the recording. The fact is I’ve had them in my life for as long as I remember, and had the whole cycle memorized for just about as long. Some of these pieces have never ceased to be as fiendishly difficult as they seemed at first sight (Nos.3, 4, 7) while many have been “in my fingers” for some time. The most underrated have in the meantime become my favourites – the harmonic ingenuity of Nos.8, 10 and 12, the folk brutality of No.23, Haydnesque wit of No.11…

It struck me as I was listening to Sicilian folk songs how much of that primeval sound found its way into the Caprices – Nos.3, 20, 23. It is the raw power of folk music, not tampered with. No composer before Bartók and Enescu had the grace and was selfless enough to do so!

How did you begin to learn the collection, do you remember which piece you tackled first?

I’d been very slow with this as I approached the whole cycle from different sides and angles. Come to think of it, I’ve only played the collection live in its entirety once (in 2012). It was then that I came to realise how saturated the first third of the cycle is both musically and technically (if one can separate the two), and how the textures gradually clarify all the way through until the end. As very few musical works (Bach solo cycle, Messiaen’s Quartet For The End of

Time, Schubert C major String Quintet) the Caprices have got a transfiguring, eternal quality to them that crystallises out of thin air…

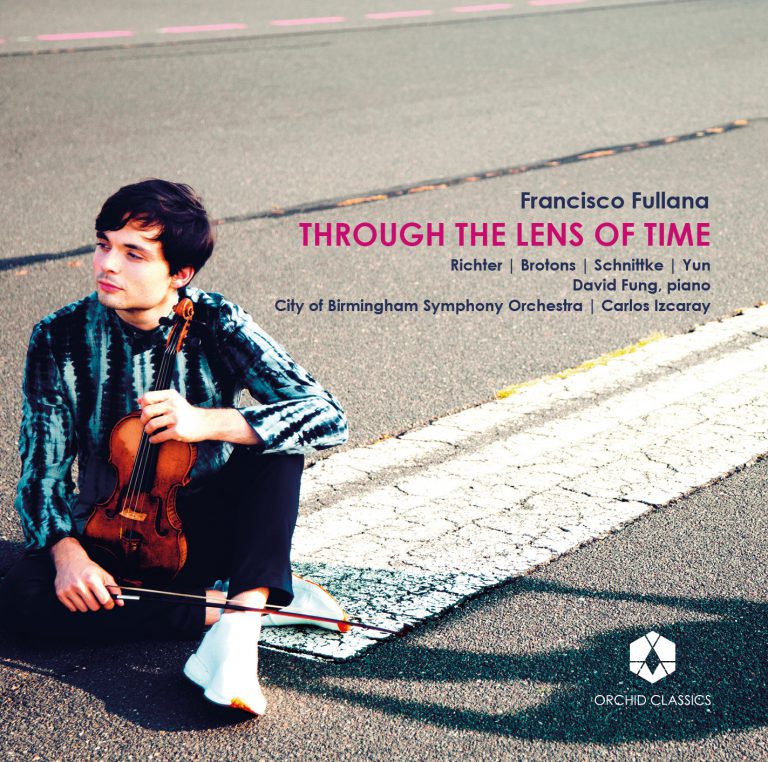

I thought mixed programmes worked better both for me and the audiences, so I was happy with just adding some Paganini to the mix, especially because his influence is so clearly heard in almost all the solo violin music that came after him. Aside from works that wear Paganini on their sleeve (Widmann, Sciarrino, Schnittke) hardly any other solo violin work escapes his hand!

You are a Professor of Violin at the Zurich Hochschule, and an International Fellow at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama – do you now enjoy watching your students pour their own blood, sweat and tears over these works?

I think I’ve seen more suffering in Mendelssohn’s Concerto…. Seriously though, I avoid giving Paganini to my students unless they explicitly wish to play it. These pieces don’t have much curricular value in the sense that they put much strain on the student and one has to be careful that they don’t bring frustration instead of improvement.

There also arises the problem of technical difficulty overshadowing the musical merits, the problem that practically no violinist that was ever involved in recording these works has to this day been able to solve. Ricci’s recording is still my favourite for the sheer fun and joy of it, but it was made before the critical edition was out and raises a few questions: what does an Andante in the 1st Caprice signify? It couldn’t very well be just the tempo, besides it’s probably also meant in the literal “walking” sense of the word. Is it worth it to adhere to the piano-forte- piano-forte scheme (chessboard!) in the 24th Caprice? The tradition weighs in strong on these type of questions, however I tried to clear up the brain and look at these works as though I’d never heard or seen them before.

Do you have a party-piece from the set for encores?

Number 16 is by far the most “encoreable”, followed closely by Nos.6, 5, 14 and 24. I’ve done No.8 once, which is slightly heavyweight for an encore. I do believe though, that all of them stand their ground (how would No.7 with both repeats be after a long concerto?) – they are wonderfully flamboyant and independent.

Surely it must feel completely different to perform a particular caprice alone, rather than within the set? Looking at the score it seems like a well-planned gym workout – a bit of bow arm to get the blood flowing before some intense stretching in the left hand – did Paganini provide a neat routine or an exhausting challenge?

A neat challenge! I believe in this particular work there was no composer sadism detected – simply an artist that was pursuing his musical vision. As regards stamina – a big factor in performing the Caprices – my approach was using as little slow practising as possible, but rather stress-training and some shock therapy thrown into the mix. I am far from disregarding slow practice as a whole (Grigory Sokolov practises everything faster than the tempo, not slower – and who can blame him?), however I felt it didn’t really help in this instance.

You studied composition, alongside violin, have the Paganini Caprices inspired any solo violin writing of your own?

It seems that everyone takes my compositions more seriously than I ever did! Sadly the last complete work I wrote was at around age 15. There was probably more influence of the likes of Gubaidulina and Shostakovich (this is the age when the brain is at its most susceptible to such influences) than Paganini.

These virtuosic pieces have been an attraction for great violinists since their inception; which existing recordings have inspired you along your own personal journey with the works?

I’ve purposely tried to keep a “clean sheet” and stayed away from any recordings before I went into the studio. After I’d received the first draft, however, I became curious and did a lot of comparative listening. What impressed me most was Ruggiero Ricci and a recent live recording by Tedi Papavrami. Many recordings I heard seemed to me fixed on motor perfection, something that never interested me very much.

Which edition did you use for this recording?

Henle! Luckily this one had two volumes including an unedited one, straight from the manuscript with just the few original fingerings and bowings, no editor work at all. Just the perfect companion.

What should we listen out for in your performance?

This might seem somewhat self-indulgent, but I’ve tried to treat these pieces as “music”, staying as truthful as possible to the original manuscript. Small example: in a Beethoven score a piano means piano and a following forte means subito forte with no crescendo, unless marked. I believe Paganini deserves the same respect – no more speculation parading as artistic licence allowed! Check out the original bowing in No.5 and the down-and-up bow ricochet in No.9 – unambiguously marked in the manuscript. I’ve taken care to create a special atmosphere in No.12 – the quirkiest and the least loved of the 24, strikingly written nonetheless.

© Ilya Gringolts

Despite his youth, Ilya Gringolts can already look back on fifteen extraordinarily successful years of his violinist career. His inquisitiveness regarding new musical challenges has shown him to be an outstanding musical personality.

After studying violin and composition in Saint Petersburg with Tatiana Liberova and Jeanna Metallidi, he attended the Juilliard School of Music, where he studied with Itzhak Perlman. In 1998 he won the International Violin Competition Premio Paganini, as youngest first prize winner in the history of the competition. As soloist he devotes himself particularly to contemporary and to seldom played works. He has premiered compositions by Peter Maxwell Davies, Augusta Read Thomas, Christophe Bertrand, and Michael Jarrell. Apart from this, he is also interested in historical performance practice. At the Verbier Festival in summer 2010, he played the complete cycle of the Bach Sonatas on a baroque violin, accompanied by Masaaki Suzuki. He is also first violinist of the Gringolts Quartet, which he founded in 2008.

In 2013/14 Ilya Gringolts will perform with the Bamberg Symphony (conducted by Eivind Aadland), the Copenhagen Philharmonic (Santtu-Matias Rouvali), the Iceland Symphony (Ilan Volkov), the BBC Scottish Symphony (Ilan Volkov), the Taipei Symphony (Oleg Caetani), the Columbus Symphony (Thomas Wilkins) and the Galician Symphony Orchestra (Osmo Vänskä). He will be performing chamber music at the festivals of Verbier and Gstaad, and, together with Maxim Vengerov, at the Barbican Centre in London.

Prior to this, Ilya Gringolts had already performed with leading orchestras over the whole world, including the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the Birmingham Symphony, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, the BBC Symphony, the Sao Paulo Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony, the London Philharmonic, the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Melbourne Symphony, the NHK Symphony, the Hallé Orchestra and both orchestras of SWR.

Ilya Gringolts can be just as frequently heard in recital programmes. He is a regular guest at the festivals of Lucerne, Kuhmo, Colmar and Bucharest

(Enescu Festival), as well as at the Serate Musicali of Milan and in the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic. Playing chamber music, he collaborates with artists such as Yuri Bashmet, Lynn Harrell, Diemut Poppen, Nicolas Angelich, Itamar Golan, Peter Laul, Nicholas Hodges and Jorg Widmann.

After numerous critically acclaimed recordings for Deutsche Grammophon and Hyperion, Ilya Gringolts has with three recent releases for Onyx devoted himself to the music of Robert Schumann: the violin sonatas 1-3 with Peter Laul (2010), the piano trios, played with Dmitry Kouzov and Peter Laul (2011), and the string quartets and piano quintet, with the Gringolts Quartet and Peter Laul (2011). In 2006, the CD Taneyev – Chamber Music together with Mikhail Pletnev, Vadim Repin, Nobuko Imai and Lynn Harrell received a Gramophone Award.

Apart from his position as violin professor at the Zurich Academy of the Arts, he is also a Violin International Fellow at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow. Ilya Gringolts plays a 1718-1720 Stradivarius, which was made available to him from a private collection.

Editor’s Choice, Gramophone Magazine

‘Wild and wonderful’ (International Record Review)