Artist Led, Creatively Driven

Schubert Song Cycles

(3 CD Set)

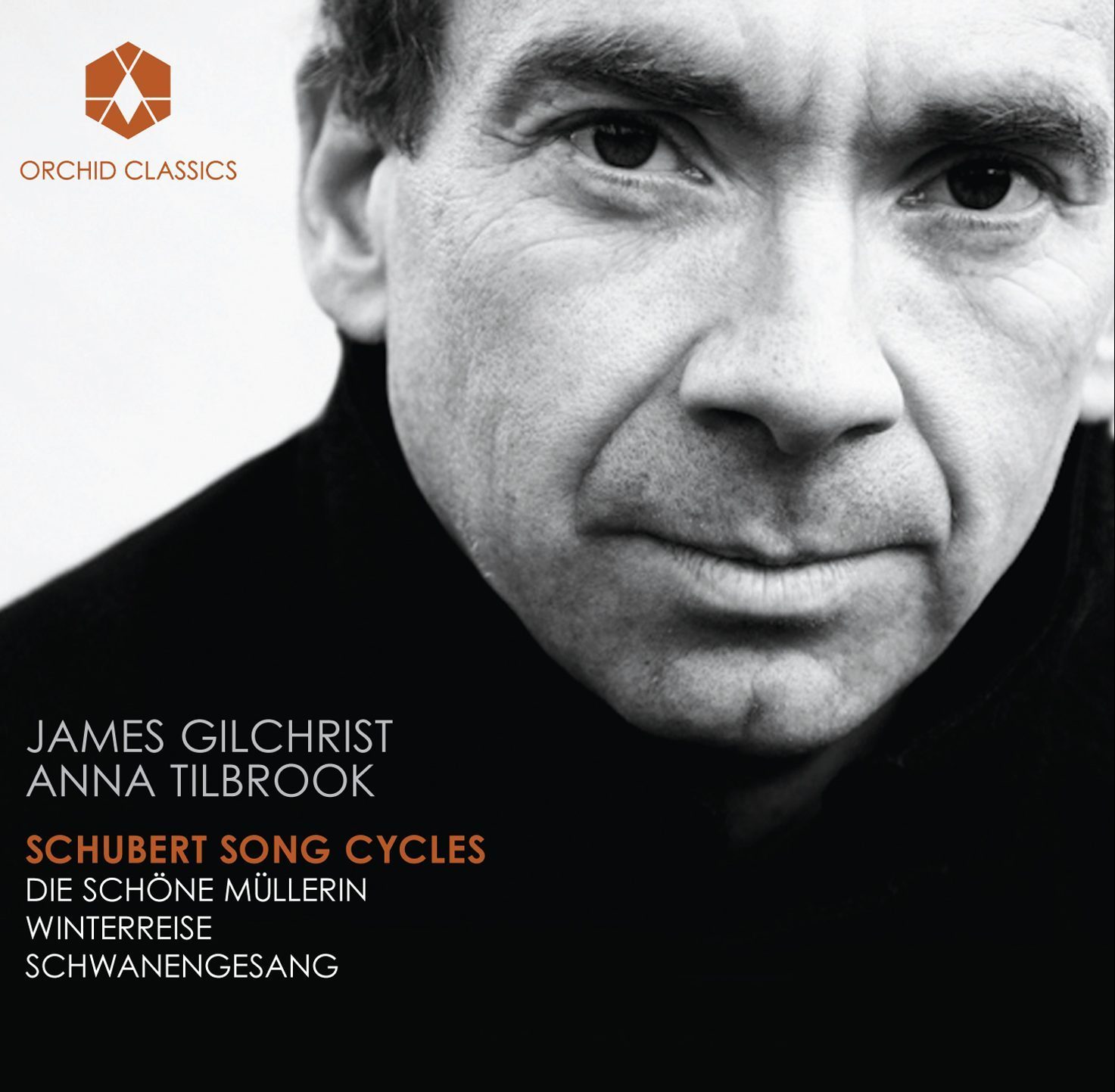

James Gilchrist

Anna Tilbrook

Release Date: September 2013

ORC100034

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

Die Schöne Müllerin

Das Wandern

Wohin?

Halt!

Danksagung an den Bach

Am Feierabend

Der Neugierige

Ungeduld

Morgengruß

Des Müllers Blumen

Tränenregen

Mein!

Pause

Mit dem grünen Lautenbande

Der Jäger

Eifersucht und Stolz

Die liebe Farbe

Die böse Farbe

Trockne Blumen

Der Müller und der Bach

Des Baches Wiegenlied

Schwanengesang, D957

Liebesbotschaft

Kriegers Ahnung

Frühlingssehnsucht

Ständchen

Aufenthalt

In der Ferne

Abschied

Der Atlas

Ihr Bild

Das Fischermädchen

Die Stadt

Am Meer

Der Doppelgänger

Die Taubenpost

Winterreise, D911

Gute Nacht

Die Wetterfahne

Gefrorne Tränen

Erstarrung

Der Lindenbaum

Wasserflut

Auf dem Flusse

Rückblick

Irrlicht

Rast

Frühlingstraum

Einsamkeit

Die Post

Der greise Kopf

Die Krähe

Letzte Hoffnung

Im Dorfe

Der stürmische Morgen

Täuschung

Der Wegweiser

Das Wirtshaus

Mut

Die Nebensonnen

Der Leiermann

JAMES GILCHRIST (tenor)

ANNA TILBROOK (piano)

SCHUBERT SONG CYCLES

Die schöne Müllerin

In Die Schöne Müllerin – the beautiful maid of the mill – we are told a story. It’s a straightforward tale of a young man looking for love and being disappointed, but Schubert and Müller have here created a work of huge power and depth, where we explore this tragedy with great empathy and pity, but also with our hearts full of despair at our own inability to alter the relentless logic of fate.

A young man has been apprenticed at a mill, and begs leave of his master to go out into the world and seek his own living. He follows a stream running down the hillside, reasoning that mill-wheels are turned by streams, so he’s sure to find a mill ere long. And by the third song, we have already arrived. The lad is taken on, and to his astonishment and delight finds that here he has found not only work for his hands, but enough for his heart too. For the miller’s daughter – the maid of the title – has quite bewitched him. He is instantly, utterly in love. The green spring world rejoices with him. He gives her the green ribbon from his lute. But of course he fails to notice that her feelings for him are not equal to his. An unwelcome visitor arrives – a huntsman, virile and attractive – whom the maid seems to find delightful. The colour green mocks him: the colour of innocence and spring and hope has turned to the colour of the hunt and of envy. The world is full of green and everywhere it now tortures him. Thrown into despair, he seeks council from the only true friend he has ever had: the stream running by the mill. And seeing this as the only means to peace, he flings himself under the waves.

For a tale of such sadness, it is striking that so much of the work is deliciously happy. It is bursting with tunes which even at a first hearing, one feels one has known for ever. The brook is effortlessly portrayed with rippling motifs, and its bubbling carries us merrily onward. We are given happiness, hope, youthful vigour, trust, and a deep delight in the natural world. And love: for he is quite overwhelmed by love. We sit with him enraptured. Time stands still. Every movement of leaf, cloud or star takes on a deep and special significance and meaning. For me this stasis in the middle of the work is crucially important: in “Tränenregen” we have one of the few moments that the two young people spend any time together. But there is no kiss, no touch, no word. He is unable even to look at her directly, but gazes at her reflection in the water. The power of his emotions overwhelms him, and he begins to weep. The banal words she – embarrassed – utters take on huge significance for him, and confirm him in his delusion of love. And so when his world tumbles, it falls from a great height, and falls rapidly. The last few songs of rage, despair and misery come headlong at us. The final song is a lullaby sung by the brook as it gently rocks its dead son and washes away his cares and troubles.

Die Schöne Müllerin is widely recognised as a masterpiece of the song genre. It is well known and much loved. Anna and I have been enormously lucky to perform this glorious work many times over many years on modern pianos and instruments more like those with which Schubert would have been familiar. As with all great works of literature and art, it is sometimes surprising to discover that what has moved countless people for many generations moves us deeply today as well, as freshly and directly as ever.

Schwanengesang

The collection of songs that has been loved for nearly 200 years as Schubert’s Schwanengesang seems to me to show Schubert at something of a turning-point in his artistry as a song-setter. Of course, it’s his last collection, and so it’s probably only my imagination, but it feels to me that in the settings of Heine, Schubert is finding a brand-new voice: he’s found in these distilled poems of his contemporary an inspiration to deal in a new way with the craft of song-setting. The Rellstab and Heine sets are so strikingly different: Rellstab with much more wordiness, long sentences with strained syntax, evokes a thicker, notier voice from Schubert. Somehow these jewels of song seem to flow. Schubert is at the height of his powers and his melodic genius is pouring forth. With the striking bare visual imagery of Heine, he finds a bolder brush-stroke, a more impressionistic setting and a breathtaking daring to be spare: ‘Die Stadt’ is almost written on one chord, ‘Am Meer’ scarcely moves. It’s tremendously exciting to perform: the raw emotional intensity allows you to dare to be ugly in tone; you can almost feel the weight of the world on Atlas’ shoulders; the shock of the deathly pallid face in ‘Der Doppelgänger’ is theatrically given.

It’s so easy to see Schwanengesang (the title doesn’t help, of course) as a work associated with end of life, with old age, even. But Schubert was young, the poets the same or younger. All the songs seem to show how much more there is to come and how much more Schubert has to say. Fate, of course, had other ideas and cut him off in his prime: experimental, daring and full of youth and hope in the future.

Winterreise

In the spring of 1827 Schubert’s friends gathered to hear him perform his newest songs. They heard at that time the first twelve songs of what we now know as Winterreise. Schubert wrote the subsequent twelve as a continuation later that year, after finding Wilhelm Müller’s complete work. His friends’ initial reaction of shock at the gloomy nature of these songs is well known. But Schubert’s belief that these were the best of him has since been supported both by his friends and, in subsequent years, by the wider musical world.

The two-part genesis of the work seems to me to be reflected in the underlying mood and subject of each part. The first twelve songs feel driven. I say this even though they contain two songs of great stasis: the ‘frozen songs’ – ‘Wasserflut’ and ‘Auf dem Flusse’. Overall the sense is one of a young man forced away. There is desperate haste and urgency – abundantly clear in ‘Erstarrung’ and ‘Rückblick’, of course – which pervade so many of the songs. ‘Lindenbaum’ and ‘Gute Nacht’ show the protagonist tearing his eyes away from all he has held dear. Those delicious moments of major-key memory and tenderness are thrust behind him in blind flight, urged by rage and jealousy (‘Wetterfahne’). The focus of attention is entirely inward: he seems hardly to notice the living world around him, so pressed is he to get away.

But the second half seems less concerned with flight. We are jolted into this new realm with ‘Die Post’. The young man’s eye travels outward. Other creatures are seen: the postman on his horse, the crow. And the major-key moments seem to belong less now to him. They are the delights of others (‘Die Post’, ‘Im Dorf’, ‘Das Wirtshaus’) or, increasingly, moments of torturing illusion (‘Nebensonnen’). And of course his thoughts, in seeking a destination, turn ever more to death. And death will not have him. Unlike the boy in Die schöne Müllerin, death cannot provide his right fulfilment. But, tormented by his own youth, we leave him restlessly transfixed by a starving old man, meaninglessly turning the handle of an organ. Ignored, lost. In a world torn away from mankind. A living death.

Decisions have to be made when presenting this work. Schubert’s published versions of 1828 result from significant re-workings of earlier manuscript drafts and fair copies, and it is sometimes hard to know whether these were fundamentally at the composer’s command or editorial suggestion. Nevertheless, we have used these versions as the basis for our recording. In particular, the transpositions of ‘Wasserflut’, ‘Rast’, ‘Einsamkeit’ (part 1), ‘Mut’ and ‘Leiermann’ (part 2) down a tone (‘Einsamkeit’ a minor third) have been retained, sometimes with regret and always following (often heated) discussion. There are also questions of tempo and style. I’ve heard it said that Winterreise is a baritone work, and ‘just sounds wrong’ with tenor, as though the darker vocal timbres better accord with the melancholy of the songs. Yet such a work only lives through constant re-examination and challenge. True, the mood is dark, but we must remember that this tragedy is one affecting the young. The man is mocked by his youthful vitality. Schubert’s approaching death was not coming in ripe old age. There’s rage here and determination. The tread of ‘Gute Nacht’ has great purpose and is no dragging plod.

This astonishing work has been much recorded and Anna and I are extremely lucky to have this opportunity to put down our performance as it is at the moment. It has developed over the years through so many performances, and been touched, I hope, by all of them. Different venues, different pianos, ourselves bringing our changing lives, and above all different audiences, each bring their own special subtleties and qualities which suffuse and give meaning to the work through each subsequent outing. There is no such thing as a definitive version. The work lives anew every time minds talk to each other through music.

© James Gilchrist

JAMES GILCHRIST

James Gilchrist began his working life as a doctor, turning to a full-time music career in 1996.

Concert appearances include Britten Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (Manchester Camerata, Douglas Boyd), Haydn The Seasons (BBC Proms, St Louis Symphony, Sir Roger Norrington), Tippett The Knot Garden (BBCSO, Sir Andrew Davis), Bach Christmas Oratorio (Tonhalle-Orchestra Zurich, Ton Koopman), Bach St Matthew Passion (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Sir Roger Norrington), Handel Belshazzar (Philharmonia Baroque, Nicholas McGegan), Stravinsky La Pulcinella (Orchestre National de Paris, Thierry Fischer) and Handel Athalia (Concerto Köln, Ivor Bolton).

As a recitalist, he has appeared at many venues throughout the UK, in New York, and at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. In his partnership with the pianist Anna Tilbrook his performances include many broadcasts for BBC Radio 3, performing Schumann cycles and Schubert songs, as well as demonstrating a special interest in English song, with broadcasts of Finzi, Vaughan Williams, Robin Holloway, Tippett and Britten. James is also partnered regularly by the harpist Alison Nicholls, with whom he has performed songs by the contemporary English composers Alec Roth, Howard Skempton (both recorded on Hyperion) and Nicola LeFanu.

Amongst his many recordings are the title role in Britten Albert Herring (Hickox), Bach St Matthew Passion (McCreesh), Bach Cantatas (Gardiner, Koopman and Suzuki), ‘Oh Fair to See'(the complete songs for Tenor and Piano by Gerald Finzi), Vaughan Williams On Wenlock Edge (finalist in the 2008 Gramophone awards) and Britten Owen Wingrave (Hickox). Recent and forthcoming releases include songs of

Lennox Berkeley (Chandos), Britten Winter Words and Leighton Earth, sweet Earth (Linn) and a ground-breaking new recording rediscovering the work of the early 20th century composer Muriel Herbert (Linn).

ANNA TILBROOK

Born in Hertfordshire, Anna Tilbrook studied music at York University and with Julius Drake at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where she was a major prize winner. She has quickly become one of Britain’s most exciting young pianists, with a considerable reputation in song recitals and chamber music, having made her debut at the Wigmore Hall in 1999. She has collaborated with such leading singers as James Gilchrist, Lucy Crowe, Sarah Tynan, Willard White, Barbara Bonney, Mark Padmore, Stephan Loges, Ian Bostridge and Gillian Keith. For Welsh National Opera she has accompanied Angela Gheorghiu, José Carreras and Bryn Terfel in televised concerts, and over several years has been associated with the Two Moors Festival in Devon, programming comprehensive surveys of the song cycles of Schubert, Schumann and Mahler. Enjoying partnerships with a number of instrumentalists, she has performed Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du Temps at St David’s Hall, Cardiff, and with the Fitzwilliam String Quartet has played chamber music by Shostakovich, a chamber arrangement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto, KV 415 and Elgar’s Piano Quintet throughout the UK. Recently she has given recitals at LSO St Luke’s, the Three Choirs Festival, Oxford Lieder Festival, and the festivals Wratislavia Cantans in Wroc?aw and Anima Mundi in Pisa. In 2006 Anna Tilbrook made her conducting debut at the Buxton Festival directing Telemann’s Pimpinone from the harpsichord.