Artist Led, Creatively Driven

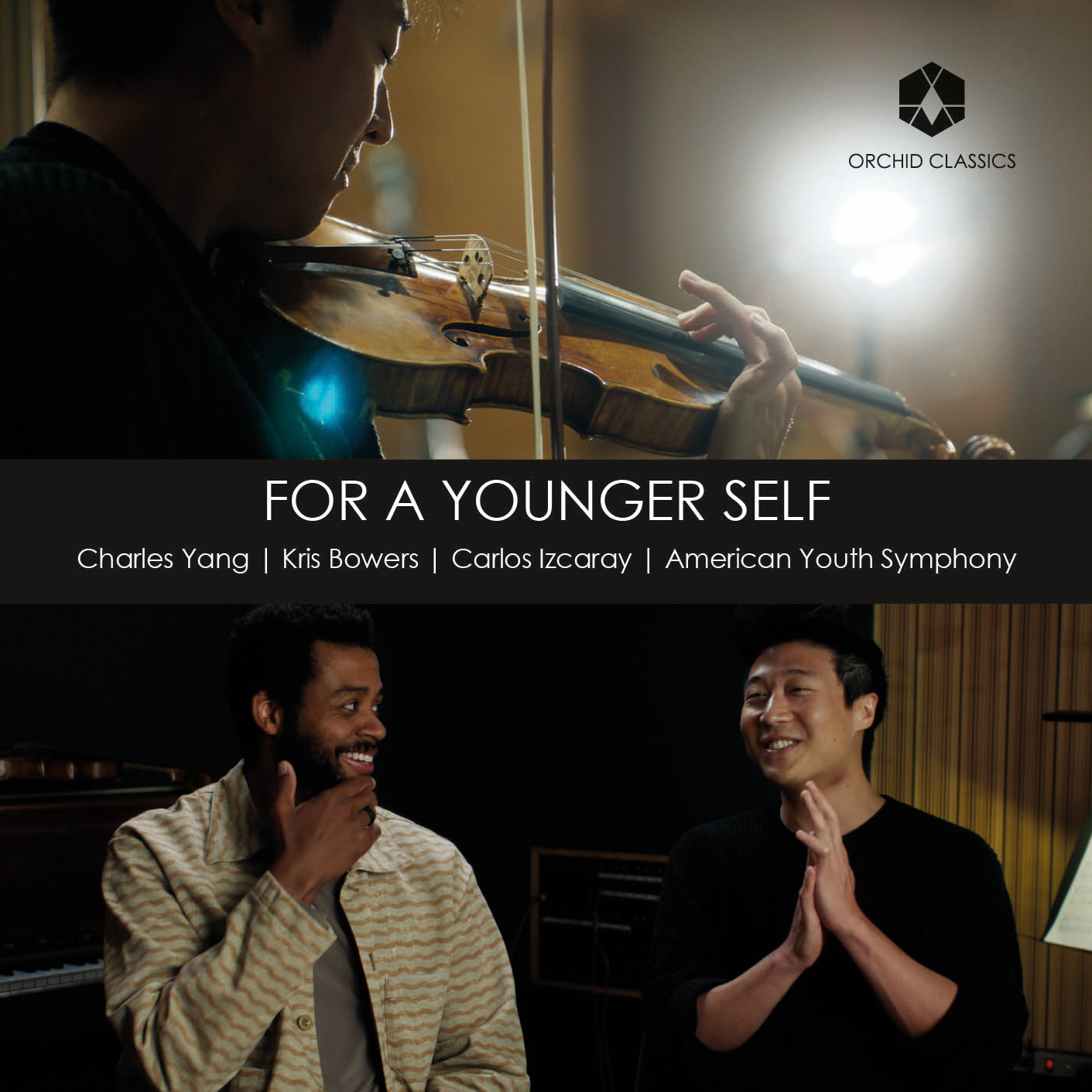

FOR A YOUNGER SELF

American Youth Symphony

Carlos Izcaray, conductor

Charles Yang, violin

Kris Bowers, composer

Release Date: July 26th

ORC100322

FOR A YOUNGER SELF

Kris Bowers (b.1989)

For a Younger Self

1. I Moderato Ma Non Troppo

2. II Larghetto (Gently)

3. III Presto (with ease and confidence)

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

4. Chamber Symphony No.1

Arranged for full orchestra (1935)

American Youth Symphony

Carlos Izcaray, conductor

Charles Yang, violin

Beginning in 1964, American Youth Symphony’s (AYS) mission has been to inspire and nurture upcoming generations of classical musicians through tuition-free fellowships for young artists. Musicians who earned a position in the orchestra gained exposure to a wide variety of symphonic music styles and performed at world-class venues, creating not only exceptionally talented artists but also citizens who are passionate about acquiring and developing skills that will promote excellence throughout their professional careers.

The genesis of For a Younger Self began when AYS patrons Sarah and Peter Mandell made a landmark pledge which included the funding of the Korngold Project, a series of compositions named in honour of Austrian-American composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957). Korngold is best known for numerous film and concert works including a popular Violin Concerto (1945), which has become part of the classical canon. In 2019, AYS commissioned Kris Bowers to compose a violin concerto as part of the Korngold Project, and AYS premiered the piece at Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles with the dynamic violinist Charles Yang as soloist in February 2020.

We all know what happened after early 2020. In March 2024 following extended effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and severe reductions from past baseline funding sources, AYS ceased operation as a result of financial challenges and the inability to sustain operations.

This album is AYS’s closing legacy.

Kris Bowers – For a Younger Self (2019)

Charles Yang, violin

Orch: 2 flutes (2nd = piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd = English horn), 2 clarinets (2nd = bass clarinet), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, triangle, glockenspiel), harp, strings, and solo violin

Kris Bowers grew up in Los Angeles, and Walt Disney Concert Hall served as an integral part of his young life. He started piano and theory lessons at The Colburn School across the street the day they opened the downtown location in 1998 and performed there with his high school jazz band, but never imagined he would be commissioned to write a piece to be premiered there.

He says, “On some level, I felt like I didn’t belong, and although I studied classical piano alongside jazz until graduating high school, it seemed like classical music just wasn’t ‘for me.’ As a young black boy, I didn’t see myself in the audience members, the classical composers that were presented, or even in the other students I was in school with. Not seeing myself in these spaces helped me create an internal narrative that I didn’t belong.”

Once Bowers discovered his love of film scoring through the music of composers like John Williams, Danny Elfman, Quincy Jones, John Powell, Howard Shore, and Jerry Goldsmith, he began to appreciate orchestral music much more, and learned to understand how the music of Ravel, Prokofiev, Beethoven, Brahms, Steve Reich, and others combined their personal musical styles with their “classical training” to tell meaningful narratives.

Both Kris Bowers and violinist Charles Yang moved to New York City as teenagers to attend the Juilliard School and bonded over the mutual feeling they had adjusting to a new and incredibly overwhelming environment as young people, overcoming fear, stress, self-doubt, and more.

Bowers shares, “This being my first concert work for orchestra, the shape and sound of the piece began to unravel throughout the composition process. Having learned so much about storytelling as a film composer, I wanted to see if I could convey a narrative through the shape and pacing of this piece… Throughout my collaboration with Charles Yang, conversations led us to reminisce on our fledgling years at Juilliard and in NYC, and so, For a Younger Self is an effort to encapsulate the essence of a young hero’s journey – one where the protagonist, embodied by Charles and his violin, embarks upon the adventure of self-discovery amidst the challenges of young life in an unfamiliar space. Our aim is for listeners to be taken on an emotional journey, guided by Carlos Izcaray, the American Youth Symphony, and the deft hands of our hero.”

“When we meet our hero at the beginning of the piece, he is somewhat melancholic and timid, and pretty soon we feel he is almost being pushed around by the orchestra. The orchestra represents life in this way and can be both the bully and the mentor. So we go back and forth between these moments of chaos and anxiety, to these gentler sections that represent the pining for tranquility, nostalgia, love, etc.”

“The second movement is a moment for our protagonist to finally have that moment of peace and reflection. It’s in this movement that we hit our “Mid-Point,” and our hero finally takes control of the narrative. He is now driving the orchestra, flowing through with much more ease and acting from a place of love rather than fear.”

“Lastly, we reach the climactic final movement in which the hero and what he’s learned is put to the test, and the ease in which he exhibits his self-confidence and assuredness amidst the chaos is on full display.”

“On some level, writing this piece became a way to send a message to the younger version of myself, in terms of finding a way to maintain balance and inner peace in this chaotic and troubling world, and also as a way to encourage and celebrate my curiosity and love for so many types of music. I am so thankful to the American Youth Symphony for this opportunity, which has helped me rewrite my own narrative that someone like me doesn’t belong in this space; performances like this can continue inspiring other young composers that have ever felt like they don’t belong.”

Schoenberg – Chamber Symphony, No.1 (1906 arr. full orchestra 1935)

Orch: 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, and strings

Schoenberg’s groundbreaking Chamber Symphony No.1 is a condensed reaction to the late-20th Century’s expansive symphonic works presented by Bruckner, Mahler, and Tchaikovsky. The single-movement work is performed with 15 instruments in a brief 22 minutes. Rearranged in 1935, Schoenberg conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the world premiere of the full orchestral version in a program of his own music on December 27, 1935 in Bovard Auditorium at USC where he was teaching; Verklärte Nacht was also part of the program.

The brevity of the Chamber Symphony is relative to other contemporary works, including Schoenberg’s Pelleas and Melisande and his D-minor String Quartet, both also in a single movement; however, the Chamber Symphony is longer than many whole multi-movement symphonies by Haydtn and Mozart.

In the Chamber Symphony, this single movement is subdivided into five very distinct parts, though they are played without a break. One way of looking at the overall plan for the piece is as a large sonata-form movement with interludes representing a scherzo and a slow movement. The grammar of Schoenberg’s lines was fresh and boundary pushing, but the spirited rhetorical gestures emerge from the sound world of Mahler and Richard Strauss, as does the emotional sincerity, which the relative concision only intensifies.

Have you ever noticed that certain composers are almost always described in the same way? Beethoven is always ‘revolutionary’, some two centuries after his revolutions. Debussy is always an ‘Impressionist’, even though the term was first applied to his music as an insult. And Arnold Schoenberg remains in the category of ‘difficult’. Almost 120 years after the composition of his First Chamber Symphony, we still tend to imagine him as incomprehensible, knotty, scandalous. Not in the way that Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was scandalous a few years later – that was an enjoyable scandal with dancers and outrageous backstage gossip. Schoenberg’s scandal was an intellectual one, a scandal of the concert hall. And who, really, wants to tackle one of those?

The First Chamber Symphony was completed in the summer of 1906, when Schoenberg was thirty-two years old. He was married, about to become a father for the second time, and newly returned to Vienna after a few years’ work in Berlin. His finances were ropey; his teaching work didn’t cover the bills, and he was composing as much as he could without any expectation of making money from it. So far, so directly comparable with life for young artists in the 2020s.

Crucially, Schoenberg had recently gained the support and encouragement of his hero Gustav Mahler. Mahler lent him money, advocated for his music, and encouraged him in his creative work even when he did not really understand what Schoenberg was trying to do. And Mahler’s own music was tremendously influential upon Schoenberg’s – as were the compositions of Brahms, Schubert, Liszt, and Wagner.

But in one crucial respect, Schoenberg’s approach was different from those of his distinguished predecessors: scale. Inspired by contemporaries such as the architect Adolf Loos, Schoenberg was attempting to strip the massive proportions of the old symphonic model right down to fundamentals. The brevity of the piece is balanced by a sense of amazingly vivid colouration, courtesy of the chamber ensemble – and we are swept along through countless changes of tempo and dynamic, with all the passionate urgency of Liszt or Wagner.

Is this piece, then, ‘difficult’? For performers, certainly! But for 21st century listeners, what seems most striking is the richness of Schoenberg’s score, and its audible connection to the music of previous generations, all lyrical melodies and impassioned climaxes. Newcomers, leave your worries about difficulty and scandal at the door: this is Schoenberg the late-Romantic, and he happily takes us by the hand to lead us into a beautifully evocative musical world.

Carlos Izcaray

Conductor

Carlos Izcaray is an internationally renowned conductor of symphonic and opera music, as well as an accomplished composer and cellist. Izcaray has served as Music Director of the Alabama Symphony Orchestra since 2015 and was Music Director of the American Youth Symphony from 2016-2024.

A strong believer of supporting the younger generations, Izcaray has worked extensively with the world’s top talents and leading music institutions, including his country’s own El Sistema. He served as Principal Cello and Artistic President of the Venezuela Symphony Orchestra prior to dedicating his career primarily to the podium.

Increasingly active and highly regarded as a composer, Izcaray’s orchestral work has been premiered by the Orquesta Sinfónica Municipal de Caracas, American Youth Symphony, Alabama Symphony Orchestra, and clarinetist Anthony McGill.

Izcaray was born into a family of several artistic generations in Caracas. He is an alumnus of the Interlochen Arts Academy, New World School of the Arts, and Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, winning top prizes at the 2007 Aspen Music Festival and later at the 2008 Toscanini International Conducting Competition. He is a dual citizen of Spain and Venezuela, and divides his time between Birmingham, AL, and Los Angeles.

Learn more at www.carlosizcaray.com

Kris Bowers

Composer

Kris Bowers is an Academy Award® winning filmmaker, Emmy and Grammy nominated composer and pianist. He won his first Academy Award® for Best Documentary Short Film for his most recent film, The Last Repair Shop, which spotlights some of the individuals working at a repair shop in Los Angeles, the last American city to provide freely repaired instruments to its public school students. Upcoming, he is scoring the DreamWorks animated film, The Wild Robot, which stars Lupita Nyong’o, Pedro Pascal, Bill Nighy and Catherine O’Hara and premieres in fall 2024.

In addition to being an accomplished filmmaker, Bowers is known for his thought-provoking playing style, creating genre-defying film compositions that pay homage to his classical and jazz roots. He has composed music for film, television, documentaries and video games. His work can be heard in recent films like the box office hit Paramount biopic, Bob Marley: One Love, Duvernay’s Origin, Warner Bros.’ The Color Purple and acclaimed television series such as Bridgerton, Secret Invasion, Mrs. America and When They See Us. He also won a Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction and Composition for his work in The Snowy Day.

He has also created original music for the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater (alongside choreographer Kyle Abraham), was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic to create a new horn concerto (2021) and he has collaborated with brands like Bang & Olufsen, Chevy, and Krug Champagne.

Bowers has multiple projects in development through Et Al Studios Productions, a production company he founded with his wife, Briana Henry.

Learn more at www.krisbowers.com

Charles Yang

Violin

Grammy Award-winning violinist Charles Yang is the recipient of the 2018 Leonard Bernstein Award and has been described by The Boston Globe as a musician who “plays classical violin with the charisma of a rock star.” A compelling vocalist, crossover artist, and improviser, he is a member of Time for Three, an eclectic, freewheeling string trio that locates itself at the busy intersection of Americana, modern pop, and classical music.

In 2023, the group received a Grammy Award in the category of Best Classical Instrumental Solo for its recording of Letters for the Future, featuring the music of Kevin Puts and Jennifer Higdon with the Philadelphia Orchestra and conductor Xian Zhang. Yang – an adventurous composer, arranger, songwriter, and collaborator – co-wrote the original score to Land, a 2021 film directed by Robin Wright.

A Juilliard graduate, he began his violin studies with his mother, Sha Zhu, in Austin, Texas, before working with Kurt Sassmanshaus, Paul Kantor, Brian Lewis, and Glenn Dicterow. Charles performs on the 1852 “ex-Soil” J.B. Vuillaume.

Learn more at www.charlesyangmusic.com

Kevin Dretzka

Executive Producer

Prior to serving on the AYS board of directors as chairman for 12 years, Kevin Dretzka was a director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Association for 10 years. He is an investor and student of music theory, composition, and orchestration who is committed to supporting classical music performance, development, understanding, and excellence in these challenging cultural times.